Sen. Deb Fischer, R-Neb., is set to read George Washington’s Farewell Address aloud on the floor when the Senate returns to session next Monday afternoon. (Bill Clark/CQ Roll Call)

CAPITOL HILL – Sen. Deb Fischer, R-Neb., will follow an annual tradition when the Senate meets again next week.

The Senate returns to session next Monday afternoon. The first order of business is for Fischer to read George Washington’s Farewell Address aloud on the floor.

The annual oration stands as one of the Senate’s most enduring customs.

A senator has read the address every year since 1896.

In recent years, the spectacle comes around Presidents’ Day.

Sen. Gary Peters, D-Mich., had the honor last year. The list of readers includes the late Sens. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, D-N.Y., John McCain, R-Ariz., Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., Hubert Humphrey, D.-Minn., and former Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, R-Tenn.

But this year, Washington’s 32-page valedictory screed bears more weight than in years past. Washington was retiring to Mount Vernon when he wrote the speech to “friends and fellow-citizens.” He used the manifest to warn Americans of the dangers of partisanship and politics if they were to maintain values in the fledgling United States.

“It is important, likewise, that the habits of thinking in a free country should inspire caution in those entrusted with its administration, to confine themselves within their respective constitutional spheres, avoiding in the exercise of the powers of one department to encroach upon another,” wrote Washington. “The spirit of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers of all the departments in one, and thus to create, whatever the form of government, a real despotism.”

One wonders how many people will tune in to C-SPAN2 or digest Fischer’s recitation of Washington’s counsel next week.

Most senators will be jetting back to the Beltway after the Presidents’ Day recess, not yet on the ground to hear Fischer’s presentation. That’s ironic considering the debate which now simmers over whether President Trump overstepped presidential authority to redistribute money for his border wall. This is especially prescient considering how lawmakers guard Congressional prerogatives. Ceding power of the purse to the executive establishes a new precedent in American government. This is precisely the concern Washington raised when he spoke of “encroachment” and limiting power within “constitutional spheres.”

TRUMP NEEDS A TRANSFER, MAY HAVE TO ROB PETER TO PAY PAUL

Policymakers always have exercised a healthy tension between the legislative branch and the executive branch. But none other than Alexander Hamilton called for what he characterized as “energy” in the executive when writing Federalist #70, the precursor set of documents which helped form the Constitution.

Hamilton demanded an active executive to curb legislative overreaches and to pose as a bulwark against Congress. In this instance, Trump asserts there’s an emergency at the border. So he needs the wall. Maybe. Maybe not. But this is why the founders formed a system of checks and balances. There’s a question about just how much latitude the president has when it comes to repurposing funds Congress designated for something else. The Constitution grants Congress the exclusive power of the purse. All presidents can do is either sign or veto bills after lawmakers decide to spend money. Trump’s plan to rejigger billions of dollars of already appropriated spending by Congress could be a problem.

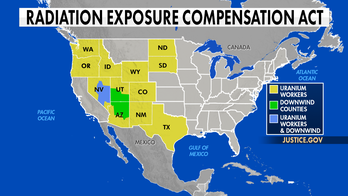

Presidents long have tested the parameters of executive authority. President Woodrow Wilson declared a “national emergency” in 1917 because of an “insufficiency of maritime tonnage” to carry U.S. agricultural and manufacturing commodities. Congress approved the National Emergencies Act of 1976, granting presidents the ability to act on any number of priorities they may deem an emergency. Presidents have declared 58 national emergencies since 1976. Thirty-one are renewed each year.

From a parliamentary perspective, Fox News is told that the National Emergencies Act is a legislative mess. It lacks focus, specificity and is inherently vague.

“It is not the gold standard for writing legislation,” confided one source.

That said, Congress can terminate declarations of national emergencies with the adoption of a joint resolution by both bodies of Congress. It needs a simple majority and must earn a presidential signature. If the president vetoes a House/Senate joint resolution, those bodies can move to override the veto with a two-thirds vote.

The House likely would seek action to revoke the national emergency as it pertains to the wall. But this process is far thornier in the Senate. The statute contains imprecise verbiage as to how the Senate may consider the legislation and whether certain, special procedural motions fly in the face of debating the statute. For instance, the law requires the Senate to vote on overturning the national emergency after “three days.” But what constitutes “three days?” Three full days of debate? A motion to adjourn is one of the most-privileged motions in the Senate. What happens if the Senate were to adjourn without first finishing work to repeal the national emergency?

CAPITOL GRAPPLES WITH COMPLICATED HISTORY ON RACE

As one source said to Fox News, “If (Senate Majority Leader) Mitch McConnell doesn’t want the resolution to come up, it won’t.”

When rushing to the Senate floor to announce that Trump would sign the spending package last week, McConnell also declared he was on board with the national emergency. A few weeks ago, McConnell’s position on Congressional action to rebuke a national emergency was hazier. But McConnell’s position grew definitive when asked by Fox News about Trump using executive authority to mine appropriations bills for wall funding.

“He ought to feel free to use whatever tools he wants to use to secure the border. I would not be troubled by that,” replied McConnell, R-Ky.

Democrats are apoplectic that Trump would go to such lengths to bypass Congress. Many Republicans are, too. That’s why a Senate vote to reverse the national emergency could prove so interesting. Some Senate Republicans also have shown a willingness to buck Trump when it comes to foreign policy. Some Republicans have broken with the administration over an early withdrawal from Syria, relaxing of U.S. sanctions on Russia and how the president dealt with Saudi Arabia following the death of Jamal Khashoggi.

The other problem staring at the Trump administration is the “Youngstown Steel Case.” The 1952 Supreme Court case Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer is thought to be the most consequential rebuff of presidential powers in history. In fact during his confirmation hearing, Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh cited the case as one of the most important rulings ever handed down by the High Court. It’s possible Trump could face a dim view on his expansion of appropriation powers at the Supreme Court. Moreover, it will be interesting to see how Kavanaugh interprets the president’s maneuver, considering his testimony about “Youngstown Steel” last year.

The question on the table is why Congress should exist if the president is able to trample on legislative spending authority.

The late Senate Majority Leader Robert Byrd, D-W.Va., long worried about what would happen to Congress if it forked over powers to the executive branch. Byrd cited the decline of the Roman Senate once the executive seized the power of the purse.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“The United States Senate would have set its foot on the same road to decline, subservience, impotence and feebleness that the Roman Senate followed in its own descent into ignominy, cowardice and oblivion,” warned Byrd.

But you don’t have to study the Romans. Consider the warnings Washington issued in his 1796 Farewell Address. Fischer will lay those all out before the Senate next Monday afternoon.