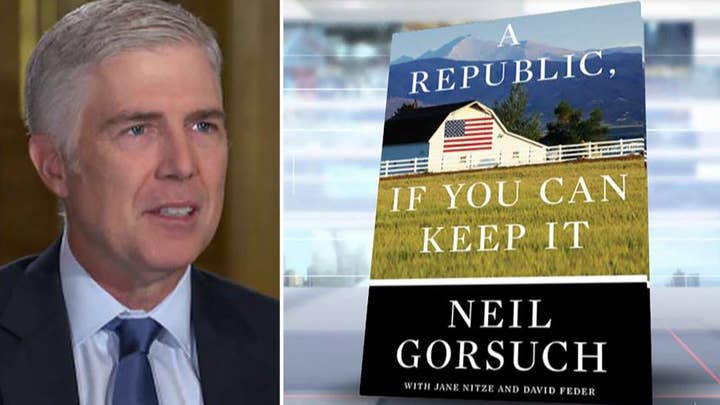

Neil Gorsuch opens up on his journey to Supreme Court in Fox News special

In his first televised interview as a Supreme Court justice, Neil Gorsuch sits down with Shannon Bream to discuss his journey to the nation's highest court. His wife Louise also talks with Bream about the journey.

I am an English girl who moved to America because I fell in love with a boy. I became an American because I fell in love with this country and its ideals.

I met Neil in England. Three months after our first date we were engaged. Within another three months, we had moved to Washington, D.C. It was a sudden, unplanned adventure, and it felt like my life had just split into a ‘before’ and ‘after.’

Unlike so many immigrants who come here because they are fleeing something – perhaps violence or political persecution – I wasn’t escaping. My story is less dramatic but shared by many.

SUPREME COURT JUSTICE NEIL GORSUCH: 'ESCAPE FROM LOOKOUT RIDGE' – HOW MY NOMINATION TRIP BEGAN

Justice Neil Gorsuch stands with his wife Louise Gorsuch on the steps of the US Supreme Court in Washington, DC, June 15, 2017. / AFP PHOTO

Neil was working long hours at a small law firm, while I spent my days navigating the endless cultural differences that became a constant reminder I was an outsider.

Who knew, for example, that you couldn’t remove a stick of butter from the carton of four and buy it separately? After all, the lady in front of me tore the twelve-egg carton down to six. And why did my husband’s English speaking grandmother need him to translate for me?

Over time, I found an America that spoke directly to me. It started with a rodeo.

The first year I lived in Washington, I discovered country music on the radio and heard the ad for a rodeo being held in Frederick, Maryland - The Beast of the East! I made Neil go with me—somewhat grudgingly, I must tell you, for Coloradans come with a healthy skepticism of rodeos this far east of Texas.

I’m a country girl and that evening opened up a whole new world for me. This was the America I would come to love. It seems trite to talk about a melting pot but the diversity of cultures and viewpoints offers a home to any soul. I had found my place.

When I became a citizen in February 2002, it was because I wanted to vote—to go all-in on the project of being in a republic premised on the right to rule oneself, and to share the obligation to make the republic work.

The English sometimes mistake American optimism for naiveté, but the positive attitude is a strength. Maybe it’s a product of the nation’s history, which began when colonial farmers successfully fought against the odds to win their independence. Maybe it has been sustained by the constant addition of immigrants who came here to forge a better life for their families through sweat and tears. Maybe it springs from the faith of the American people that their country and its foundational principles are a force for good. Wherever it comes from, I find that optimism infectious.

Over the last two years, our quiet life in Colorado has exploded into a public place. Neil’s words and actions are scrutinized and interpreted—often in ways neither of us recognize. But there have also been countless people who have stopped to wish Neil well, to tell him a joke, and even (this is real) mailed him food because he looked a bit worn during his Senate hearing.

The positive experiences have been truly meaningful to us. Individuals from all political persuasions have wished us well out of kindness. A kindness that I have come to associate with the vast majority of my fellow citizens.

More from Opinion

The title of Neil’s new book ("A Republic, If You Can Keep It") resonates with me. The gist of it is all in the inflection: “if you can keep it,” he says. Our Constitution protects the people’s individual freedoms, but more importantly, it secures our right to govern ourselves.

When I became a citizen in February 2002, it was because I wanted to vote—to go all-in on the project of being in a republic premised on the right to rule oneself, and to share the obligation to make the republic work. Neil’s book, in part, is a plea to all Americans to see that task as their responsibility, and not that of judges or government bureaucrats.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Of course, we know that self-government is also messy. When neighbors have the right to rule each other through the ballot box, they might argue bitterly.

Nowadays many hear complaints that the intensity of the noise and turmoil in today’s political culture is new, but I would refer them to our history. To me, the raised voices should be celebrated, not reviled. They are not a symptom of dysfunction but a sign of health, a demonstration that the nation can withstand the rancor that comes with self-government and, eventually, get on with the rodeo.