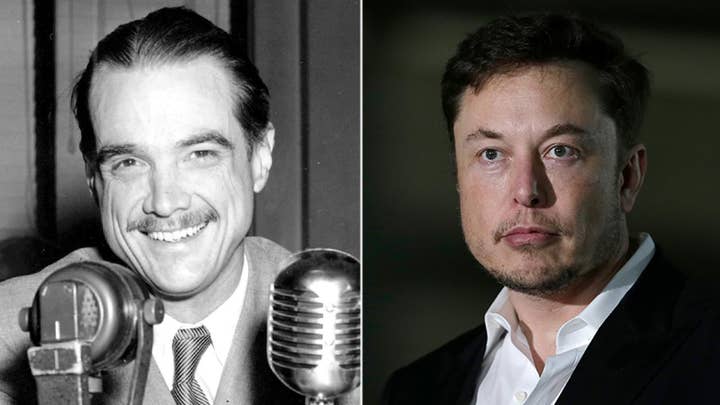

New, creepy details revealed about Howard Hughes in new book

Karina Longworth's new book, “Seduction: Sex, Lies, and Stardom in Howard Hughes’s Hollywood,” reveals bombshell new insights into the life of Howard Hughes.

Before there was #MeToo and Harvey Weinstein, there was Howard Hughes, a film producer, owner of RKO Pictures in the late 1940s through the 1950s, and one of the world’s richest men. He was also a legendary playboy — and an often emotionally and physically abusive man who seduced, harassed and cajoled scores of famous actresses, including Ava Gardner, Bette Davis, Lana Turner and more, as Karina Longworth reveals in her new book, “Seduction: Sex, Lies, and Stardom in Howard Hughes’s Hollywood” (Custom House), out now.

Ava Gardner recalled Howard Hughes as a great lover, referring to him as the man who “taught me that making love didn’t always have to be rushed.” But his anger often eclipsed his passion, as Gardner, then in her early 20s, learned the hard way after refusing to accompany Hughes’ driver to pick him up from the airport.

After telling Hughes she had been with her ex-husband, actor Mickey Rooney, instead, Hughes lost control.

“He swung at her, and the next thing she knew, she had fallen back into a chair. Then, she recalled, Hughes ‘jumped at me and started to pound on my face until it was a mess,’ ” Longworth writes.

Gardner, however, fought back. She found an “ornamental bronze bell” on the mantelpiece, picked it up and struck him on his face, splitting his forehead open and knocking loose two teeth.

Livid at what he’d done to her, Ava continued the beating while Howard was down, grabbing a chair and hitting him some more. Finally, her maid walked in and put a stop to it.

Hughes and actress Katharine Hepburn, Longworth writes, were “kindred spirits” who would “skinny-dip [by] diving off the wing of a seaplane in the middle of Long Island Sound.” They also shared a robust sex life, with Hepburn calling him “the best lover I ever had.”

Bette Davis was equally enamored, if not entirely impressed, with Hughes’ seductions.

“I was the only one who ever brought Howard Hughes to a sexual climax, or so he said at that time,” she once claimed.

“I believed it when he told me that. I was wildly naive at the time. It may have been his regular seduction gambit. Anyway, it worked with me, and it was cheaper than buying gifts. But Howard Huge, he was not.”

Hughes and Ginger Rogers’ on-again/off-again love affair lasted years, with Hughes gifting her a 5-karat emerald engagement ring in 1940 and telling her he would build her a mansion. Soon, though, he demanded that Rogers be available for him whenever he desired, and “she [began] to suspect he was having her followed and that her phone calls were being surveilled.”

After Hughes blamed Rogers for a car accident she wasn’t even in — she had refused to accompany him to a dental appointment, and he was so angry about this that he crashed his car — she finally broke it off.

“Howard wanted to get himself a wife, build her a house and make her a prisoner in her own home while he did what he pleased,” Rogers later wrote. “Thank heavens I escaped that.”

As Hughes got older, his targets became younger, his controlling nature, more severe.

Hughes was 35 when he met Faith Domergue, then 16 and an actress under contract with Warner Bros., at a party on his yacht. After taking her out for a private sail, Hughes pursued her relentlessly.

While she initially had no interest, he wore her down and proposed marriage three months later, giving her a diamond ring and telling her, “You are the child I should have had.” In time, his pet name for her became “Little Baby”; her loving nickname for him was “Father Lover.”

The pair never married — proposals, it turned out, were a primary tool in Hughes’ seduction arsenal — but within weeks of his proposal, he purchased her contract from Warner Bros.

“Suddenly, within a matter of days,” Domergue later recalled, “I and my emotional and professional destiny were completely in his hands.”

Hughes scheduled her life so completely, from acting lessons to school tutoring, that he controlled it all.

He hired her a full-time driver who was charged with writing down everywhere she went.

He also moved her parents into a house around the corner from him, charming (and bribing) them with his largesse and giving her father and grandfather jobs in his factories.

Soon, she no longer had friends, wasn’t allowed to drive herself anywhere, was trapped alone — Hughes rarely returned home — in a 30-room mansion she found haunted and creepy, and had her family completely in Hughes’ debt.

Hughes, who carried on with Gardner, Turner and a then-teenage Gloria Vanderbilt while still with Domergue, would never marry her or make her a star.

He didn’t cast her in a movie for years and since he owned her contract, she couldn’t act for anyone else. Whenever she tried to leave him, Hughes would appeal to her mother, who would pressure her into staying.

Years later, Domergue wrote an autobiography that was never published. Longworth suggests that the evidence points to the book having been killed by people connected to Hughes.

But if his relationship with Domergue became a cautionary tale for young actresses, for Hughes, it was a template.

Whenever he saw a picture of a pretty teenage actress, he sought to get her under contract — and under his full control — right away, installing them in his apartments, scheduling every moment of their lives and hiring each a personal driver who was also his spy.

He would then leave very specific demands for how these women were to be handled, some of which revealed odd sexual proclivities.

“If we saw a bump in the road, we were supposed to slow down to a maximum speed of 2 miles an hour and crawl over the obstruction so as not to jiggle the starlet’s breasts,” a Hughes driver named Ron Kistler later revealed.

“Hughes was one of the world’s consummate t-t men, and he was convinced that women’s breasts would sag dangerously unless treated gently and supported at all times.”

Stories of Hughes’ pursuits are a litany of creep, including that of actress Terry Moore when he was 43 and she was 19.

As she wouldn’t sleep with him until they were married, Hughes married her on a boat — but did so in international waters.

Records of the wedding mysteriously disappeared after the ceremony, and the dispute over whether they were ever really married led to a years-long legal battle after his death.

When Hughes saw a picture of 23-year-old Italian beauty Gina Lollobrigida in 1950, his representatives offered plane tickets for her and her husband to fly to LA to meet Hughes, but sent only one ticket.

When she arrived in LA, believing it to be the beginning of a career in Hollywood, she was provided a hotel room with guards outside her door.

“Unless accompanied by Howard, she wasn’t allowed to leave the room, and Hughes had arranged with the front desk to block her phone calls,” Longworth writes.

When Lollobrigida finally had the chance to talk “business” with Hughes after a month and a half as a virtual captive, he tried to persuade her to divorce her husband and marry him.

She demanded a plane ticket home but before she left, Hughes insisted on throwing her a goodbye party.

At around 3 a.m., he then persuaded a drunken Lollobrigida to sign a contract.

While she went on to become a major star in Europe, her fame did not immediately cross the ocean because due to the contract she had signed, she was forbidden for years from working in America for anyone but Hughes. Given his behavior, she refused to work with him.

Hughes, famously reclusive and mentally ill in his later years, died in 1976 at age 70.

“By the end of Hughes’ life, when he was a codeine addict who spent his days and nights nodding in front of the TV, ” writes Longworth, “the former star aviator playboy would suddenly perk up when an actress he had once spent time with appeared on the screen.

“Hughes would allegedly call over one of his many aides, point and say, ‘Remember her?’ and then drift off into a grinning daydream of better days, days when his power to draw women to him and control not just their emotions but their movements, appearances and identities was apparently limitless.”

This story was originally published by the New York Post.