As one of Turkey's top television journalists, Sedef Kabas is worried about what is happening to freedom of the press. (FoxNews.com)

As one of Turkey’s most recognizable journalists, Sedef Kabas is used to asking the questions.

But on a Friday morning in December, it was three plainclothes police officers who knocked on her door bearing a search warrant and asking if she had authored a tweet referring to a recent corruption scandal that ensnared high-level officials in the administration of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

“Yes I did,” said Kabas, who was wearing a bathrobe and had just packed her five-year-old son off to school.

Kabas was not one to dodge questions, especially those that involved her work. In the tweet the police were inquiring about, Kabas, who has nearly 60,000 followers, noted that the investigation was squelched on orders of a high-level prosecutor.

“I was the one who sent that tweet and I am still that person, I am not denying that.”

“Do not forget the name of the chief-prosecutor who cancelled the investigation, Hadi Salihoglu,” it read.

Turkish authorities claim that, because Salihoglu prosecutes terrorists, the tweet invoking him potentially interfered with those efforts. Kabas and her supporters believe that is a flimsy pretext, just the latest in an escalating crackdown on the media by the government of Erdogan, who himself once promised to “eradicate” Twitter in Turkey.

“‘Why are they here?’ Sedef said in a recent interview, referring to the police. “There are all these things going on in Turkey, all of this corruption and bribery and crime and yet they are at my door, which really made me furious.”

After opening the door to three plainclothes officers, Kabas asked them to wait outside while she contacted the lawyer who represents her in business. He advised her to call the Istanbul Bar Association, where an official told her the search was illegal. Still, believing she had nothing to hide, Kabas let the police in.

“I said they were free to make any search they wish,” she recalled. “I was the one who sent that tweet and I am still that person, I am not denying that.”

Police confiscated Kabas’ laptop and cell phone, as well as her son’s tablet. When they were finished, they took her in for questioning in Gayrettepe, a district of Istanbul. There a prosecutor, Vedat Yigit, grilled her about the tweet.

“I said the reason why I sent this tweet is something I have said a hundred times and I will say it again,” Kabas said. “I am critical of his decision. I don’t believe in the fact that the biggest, the largest, the deepest investigation of corruption and bribery in Turkish history should be dropped.”

The scandal she was tweeting about went public in December 2013, and implicated members of then-Prime Minister Erdogan’s family, four ministers from his ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) and high-level businessmen. Among the material implicating Erdogan was a series of incriminating phone call recordings released on Twitter, including one in which Erdogan appears to instruct his son to hide tens of millions of dollars. Erdogan confirmed the authenticity of some recordings, but said they were edited to distort their meaning as part of a plot by his one-time political ally Fethullah Gulen, a U.S.-based Turkish cleric.

Since the scandal broke, the government has insisted there is nothing to the accusations, dismissing them as part of a so-called “parallel state’s” attempted coup. Gulen, a one-time ally who Erdogan has since said should be extradited to Turkey, has denied any illegal involvement in the case.

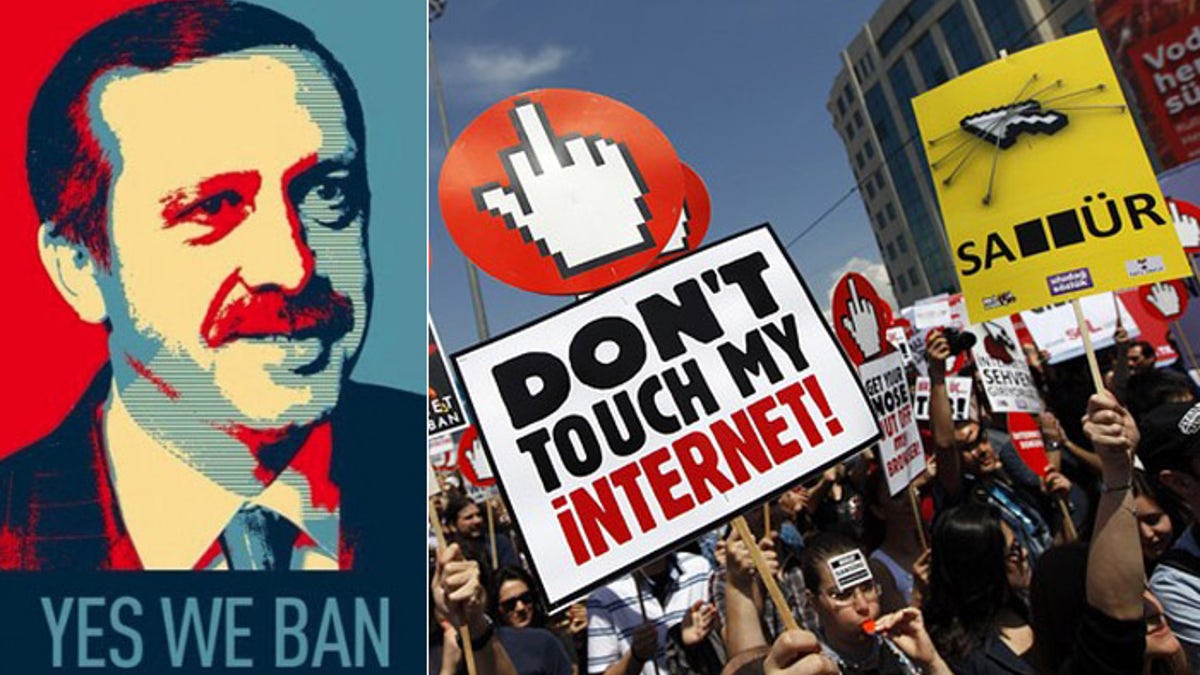

The Erdogan administration, which has already cracked down on social media in an effort to shut down criticism over its heavy-handed suppression of street demonstrations during the Gezi Park movement, subsequently banned Twitter and YouTube access in a move that drew international condemnation and prompted a backlash from critics. One memorable editorial cartoon, patterned after President Obama’s “Yes we Can” posters, showed Erdogan and bore the phrase “Yes we Ban.”

The corruption case took a circuitous path on its way to the dustbin. The original prosecutor for the case was replaced, while Salihoğlu was appointed the new chief prosecutor for Istanbul. The case was dropped 10 months later for lack of evidence, with claims the evidence had not been collected properly. A contentious vote in the Erdogan-controlled Turkish parliament blocked the four now-former ministers from facing charges.

“I am not afraid of going to court,” Kabas said, who is due to appear before a judge on April 7. “I wonder why the ministers who resigned do not want to go to court?”

After the initial indictment, which carries a sentence of up to five years in prison, Kabas is facing a further indictment, which carries a sentence of five years and four months, for showing "resistance" to the police when they searched her home in December.

Kabas isn’t the only high-profile Turkish figure targeted by prosecutors. Merve Buyuksarac, Miss Turkey 2006, was recently called into an Istanbul court after quoting a satirical poem on her Instagram account that was critical of Erdogan. That came after a 16-year-old boy, Mehmet Emin Altunses, was arrested by police at his school after making a speech criticizing Erdogan and his AK Party. The boy was released, but still faces up to four years in jail if found guilty of insulting the office of the president, which is a crime in Turkey.

The accusation against Kabas went further, partly because of her high profile as a journalist. Under questioning by Yigit, the same prosecutor who brought the case against former Buyuksarac, Kabas was asked whether she had any intention to tie Salihoglu to any sort of terrorist group.

“I said no, even the word terrorist or terrorist organization does not come to my mind when I think about him. That is not my terminology,” she said.

After a career of asking questions, Kabas said she is sad to see how people are being prosecuted for it.

“My occupation is based on questions, journalism is based on questions,” she said. “But unfortunately, in recent years, the ones who are ruling the country and hold critical positions, they are afraid of questions. They do not like to be questioned, so they see just one side of Turkey, and rule it accordingly.”