EPA disaster has implications far beyond Colorado

Agency says it spilled 3 million gallons of contaminated wastewater into the Animas River

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. – Anger was mounting Monday at the federal Environmental Protection Agency over the massive spill of millions of gallons of toxic sludge from a Colorado gold mine that has already fouled three major waterways and may be three times bigger than originally reported.

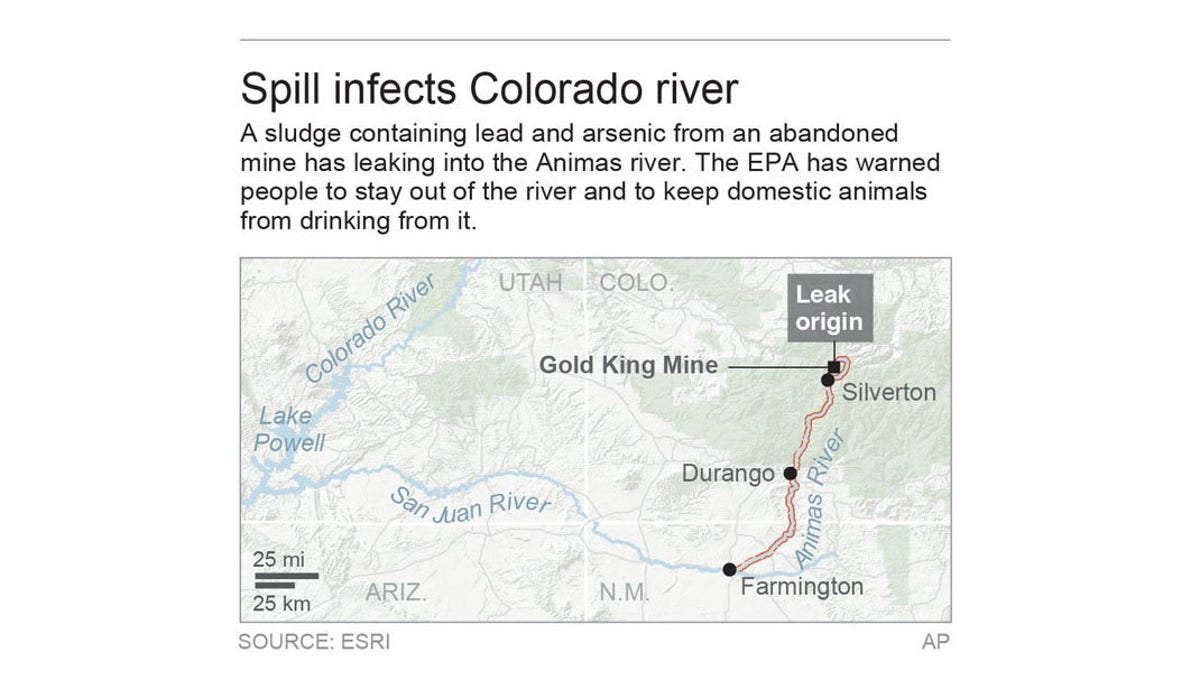

An 80-mile length of mustard-colored water -- laden with arsenic, lead, copper, aluminum and cadmium -- is working its way south toward New Mexico and Utah, following Wednesday's accidental release from the Gold King Mine, near Durango, when an EPA cleanup crew destabilized a dam of loose rock lodged in the mine. The crew was supposed to pump out and decontaminate the sludge, but instead released it into tiny Cement Creek. From there, it flowed into the Animas River and made its way into larger tributaries, including the San Juan and Colorado rivers.

"They are not going to get away with this," said Russell Begaye, president of the Navajo Nation, which intends to sue the EPA.

“They are not going to get away with this.”

Visible from the air, the toxic slick prompted EPA Region 8 administrator Shaun McGrath to acknowledge the possibility of long-term damage from toxic metals.

"Sediment does settle," McGrath said. "It settles down to the bottom of the river bed."

McGrath said future runoff from storms will kick that toxic sediment back into the water, which means there will need to be long-term monitoring.

The toxic waste passed through Colorado's San Juan County on Saturday, heading west. People living along the Animas and San Juan rivers were advised to have their water tested before using it for cooking, drinking or bathing. That was expected to cause major problems for farmers and ranchers, who require large quantities of water from the river for their livelihoods.

New Mexico Gov. Susana Martinez inspected the damage in Farmington over the weekend and came away stunned.

"The magnitude of it, you can’t even describe it," she said. "It’s like when I flew over the fires, your mind sees something it’s not ready or adjusted to see."

The EPA and the New Mexico Environment Department plan to test private wells near the Animas to identify metals of concern from the spill. Tests on public drinking water systems are handled by the state environment department, the agencies said.

Begaye said Saturday at a community meeting in Shiprock, N.M., that he intends to take legal action against the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for the massive release of mine waste into the Animas River near Silverton, Colorado.

"The EPA was right in the middle of the disaster and we intend to make sure the Navajo Nation recovers every dollar it spends cleaning up this mess and every dollar it loses as a result of injuries to our precious Navajo natural resources," Begaye said. "I have instructed Navajo Nation Department of Justice to take immediate action against the EPA to the fullest extent of the law to protect Navajo families and resources."

Begaye said the plume of sludge has made its way into the San Juan River and is wending through the Navajo Nation, the nation's largest Indian reservation. It is expected to reach the heavily used Lake Powell by Wednesday.

Officials are warning people along the affected rivers to test water before using it for drinking, cooking or bathing. (AP)

David Ostrander, an EPA spokesman, said last week the agency is taking responsibility for the incident.

"We typically respond to emergencies, we don't cause them, but this is just something that happens when we are dealing with mines sometimes," Ostander said.

The infiltration of toxic material is a haunting memory for the Navajos who are still reeling and experiencing the adverse health effects of a uranium waste spill into a river outside of Gallup, N.M., some 36 years ago. On July 16, 1979, a dam failed in a uranium waste pond spilling 1,100 tons of solid radioactive mill waste and approximately 93 million U.S. gallons of acidic and radioactive tailings solution into a nearby river tributary.

There have been claims the amount of radiation released in the Churchrock incident exceeded Three Mile Island.

The mustard-colored plume stretched 80 miles at one point. (AP)