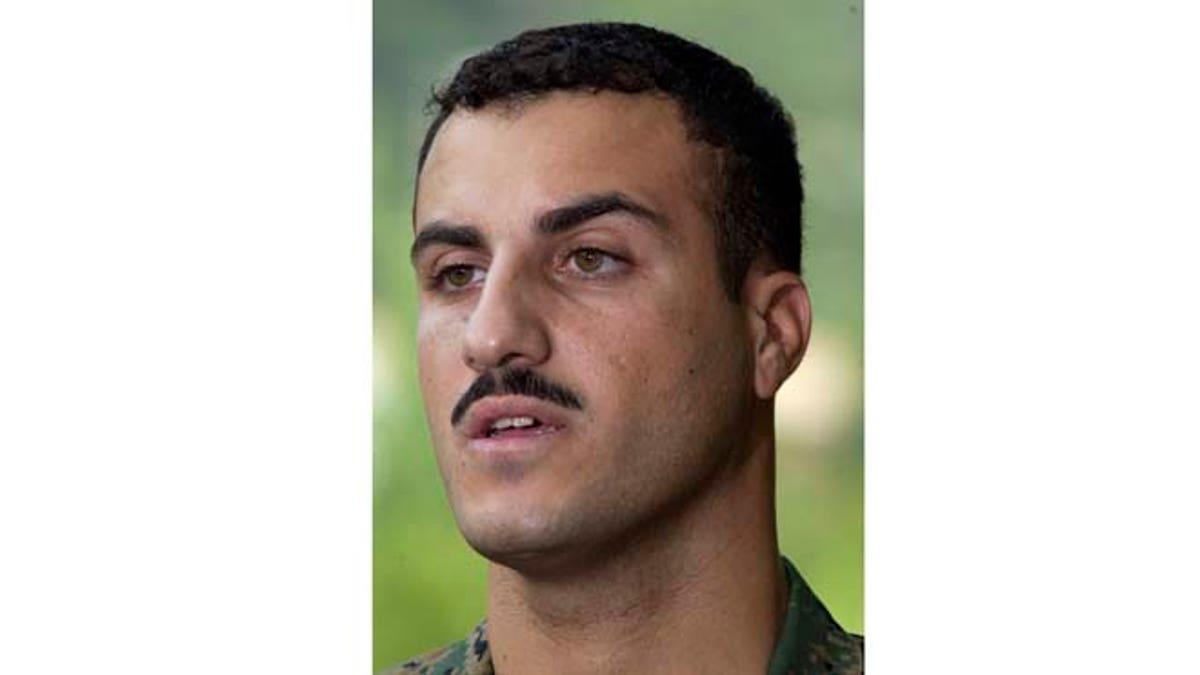

July 19, 200: In this file photo, Marine Cpl. Wassef Ali Hassoun makes a statement to the press outside Quantico Marine Base in Quantico, Va. (AP)

CAMP LEJEUNE, N.C. – A defense attorney said Thursday that a Marine accused of deserting his unit a decade ago in Iraq was kept in Lebanon for eight years while he faced a military trial there.

The Marine officer presiding over the hearing for Cpl. Wassef Hassoun adjourned the proceeding for at least a week to allow defense attorneys to translate Lebanese documents they say support his case.

The hearing officer, Lt. Col. Scott W. Martin, will eventually recommend whether Hassoun should face a military trial on charges including desertion as part of the Article 32 process, the military equivalent of a grand jury. A Marine general will have the final say on whether to try Hassoun.

Martin has given the defense at least until Aug. 27 to translate the documents, and no new court date has been set.

Defense attorney Haytham Faraj says Hassoun, 34, was kept in Lebanon for years for court proceedings triggered by U.S. accusations that he had deserted. Faraj said documents show Hassoun was tried and convicted by a Lebanese military court on charges that mirror the U.S. desertion charges. He said the Lebanese government tried Hassoun at the behest of the U.S. but did not elaborate.

Faraj said that as soon as the court proceedings in Lebanon ended, Hassoun contacted U.S. officials saying: "I need to get back to the U.S. The Lebanese have been holding me."

The case began in June of 2004 when Hassoun mysteriously disappeared from a base in Fallujah in western Iraq. About a week later, he appeared in a photo purportedly taken by insurgents wearing a blindfold and with a sword poised above his head.

Hassoun turned up days later at the U.S. Embassy in Lebanon and said he had been kidnapped by Islamic extremists and held for 19 days. A group called the National Islamic Resistance/1920 Revolution Brigade claimed responsibility for his capture.

"It strains logic that he would flee and then turn himself in to U.S. authorities weeks later," Faraj said.

But the military doubted his story, and he was brought back to the U.S. He was allowed to visit relatives in Utah in December 2004 when he disappeared again. A hearing, called an Article 32 proceeding, was canceled in January 2005. His commanders then officially classified him as a deserter.

Military prosecutors say Hassoun's whereabouts were unknown for years until he contacted U.S. officials in 2013.

Faraj said little about the purported 2004 kidnapping other than Hassoun was able to get away from his captors by using unique skills he developed as a serviceman and translator familiar with local Iraqis.

Prosecutors argue that there is overwhelming circumstantial evidence that Hassoun was unhappy and fled the Marines in Iraq and later fled to Lebanon in 2004. They gave the hearing officer statements by witnesses who said Hassoun was unhappy with his deployment and how the U.S. was interrogating Iraqis. Prosecutors say Hassoun packed a bag and withdrew hundreds of dollars shortly before his disappearance from his unit in Iraq.

"What we do have is circumstantial evidence, and that evidence is overwhelming," said Capt. Christopher Nassar, one of the prosecutors.

Military officials say that around the time of his 2004 disappearance, a marriage for Hassoun had been arranged with a woman in Lebanon. Hassoun and the woman are now married and have a son who has dual U.S. and Lebanese citizenship.

Nassar said that even if Hassoun were tried in Lebanon, it doesn't alter the Marines' jurisdiction over the desertion case.

Hassoun, who was born in Lebanon and is a naturalized American citizen, enlisted in the Marine Corps in January 2002 and was trained as a motor vehicle operator. He was serving as an Arabic translator at the time of his disappearance in June 2004.

Retired Maj. Gen. Walt Huffman, a Texas Tech University law professor who previously served as the Army's top lawyer, said he finds it very unusual that a foreign government would try an American serviceman on charges of deserting the U.S. military.

For example, in Germany and Japan where there are U.S. military bases, local authorities can try U.S. servicemen on certain criminal offenses, but they'd have no interest in pursuing military charges such as desertion.

"I find that very unusual," he said.

In desertion cases, he said it can be difficult to prove the serviceman planned never to return.

"The hardest thing is proving that they intended to stay away permanently," he said.