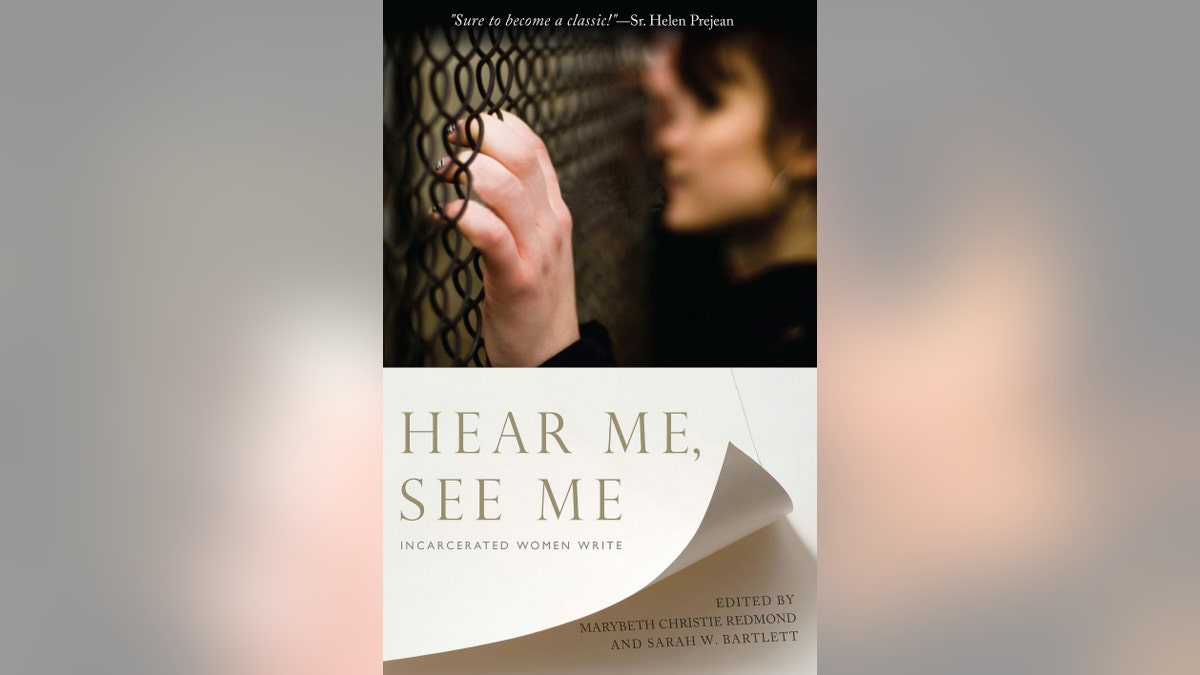

This 2013 image released by Orbis Books shows the cover a book titled "Hear Me, See Me, Incarcerated Women Write," by Marybeth Christie Redmond and Sarah W. Bartlett. The book contains prose and poetry written by 60 female inmates in Vermont’s only women’s prison in South Burlington, Vt. (AP Photo/Orbis Books) (The Associated Press)

SOUTH BURLINGTON, Vt. – Elaina Decker was full of rage, and if anyone gave her a hard time in prison, she'd act on her anger.

But, she's gentler now. Decker has put aside her anger and worked on discovering who she really is. That transformation has come through writing and the support of a weekly writing group at Vermont's Chittenden Regional Correctional Facility that has helped her come to terms with her past and, perhaps most importantly, with her brother's suicide nine years ago.

"I don't do that anymore because I don't have to," she said of acting out of anger.

About a dozen women convicted of crimes ranging from assault, forgery and drug offenses to armed burglary and murder come together each week to try to make peace with themselves and connect with others by putting their raw emotion into words on paper.

Now, prose and poetry and artwork from about 60 of the inmates are available in a book called "Hear Me, See Me, Incarcerated Women Write," published by Orbis Books.

"These straight-from-the-gut writings by incarcerated women will break your heart and put it back together again," wrote Sr. Helen Prejean, author of "Dead Man Walking" of the book.

The inmates write of the pain of childhood traumas, addictions, missing children and loved ones, being behind bars and trying to better and heal themselves. They view the weekly group as a sacred space where they feel safe, are not judged, and can heal. Those are the qualities instilled by the two women from outside the prison who started the circle as volunteers in 2010 and offer the women so much more than a chance to write.

"It's therapeutic," said the 49-year-old Decker who was imprisoned for a drug felony and then violating probation.

"I guess I learned to deal with my brother's suicide here. It took nine years," she said as tears filled her eyes. "It's a great opportunity for self-exploration."

Marybeth Christie Redmond, a journalist and Sarah Bartlett, who founded Women Writing for (a) Change — Vermont, LLC, started the prison writing circle. The program is now funded with a $30,000 donation from an unidentified benefactor.

Many of the women come from generations of poverty, have suffered some sort of childhood trauma like sexual abuse and have some mental health issue, Redmond said. Addictions, substance abuse and dysfunctional relationships are common.

The program provides an outlet for the women to express themselves in a way that communicates beyond the walls of the facility, Vermont Corrections Commissioner Andrew Pallito said.

"The writings, as an accumulation, help to show the challenges that many of the women face and identify the barriers in front of them," Pallito said.

The sale of the $25 book is expected to cover the cost of publishing 1,500 copies of it. Any proceeds would go back into the writing program.

Recently, the women sat around a table and, one at a time, read aloud comments and praise from people who attended a book launch in Burlington on Oct. 3.

Then, after a volunteer recited a poem called "An Ordinary Life," they put pens to paper and wrote for 15 minutes. They wrote of the pain of being away from their children, the constant noise in prison — chatter, the jingling of guards' keys, doors opening, closing — and being accepted by others despite their past.

As each women read theirs aloud, the others jotted down lines that struck them. As they do each week, the women called out the lines at the end of the session — a sort of live, running poem that is transcribed and read the following week.

"The beauty that awakens us from behind the walls of imprisonment;" ''I'm not afraid and all alone;" "Heaven forbid one of us escape into the realm of happiness and light;" ''The murmur of her heart understanding my sadness is what keeps me going," were among their writings.

Redmond doesn't excuse what the women have done, and a number who had been released have been returned to prison. But, she and Bartlett hope to give the women a voice and guide them in making better choices when they are released.

Norajean LaManna of Brattleboro, who suffers from depression and post-traumatic stress disorder and is in a wheelchair, has attended the writing circle from the start.

"It's the best thing I've ever decided to attend," said the 52-year-old LaManna, who was convicted of armed assault and robbery and been released from prison twice but relapsed into drugs both times.

"It's a way to deal with anger, fear, frustration, not only toward others but toward myself," LaManna said.