BOISE, Idaho – A United Airlines pilot died after suffering a major heart attack while flying from Houston to Seattle, forcing crew members to make an emergency landing in Idaho while two doctors on board did CPR in the first-class cabin.

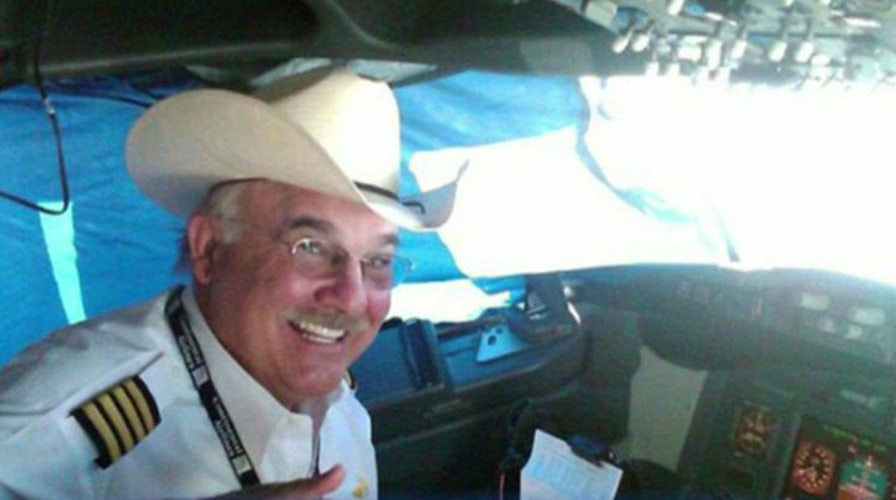

Pilot Henry Skillern, 63, of Humble, Texas, was still alive when firefighters and paramedics ran to his aid Thursday night on the Boise Airport tarmack. He died a short time later while being treated at Saint Alphonsus Regional Medical Center, spokeswoman Jennifer Krajnik said.

Skillern had been a pilot for United Airlines for 26 years.

Boise airport spokeswoman Patti Miller said it's not uncommon for a medical emergency to force a plane to divert to the nearest airport. The Boise airport has had three such diversions in the past two days, she said. But it's rare for a serious malady to strike pilots who undergo regular medical screening to keep their Federal Aviation Administration certification current.

Passengers aboard the Boeing 737-900 flown by Skillern seemed to handle the emergency well, Miller said.

"It seemed like they felt that everything that could be done, was being done," she said. "The passengers were concerned for him, but everyone was very calm."

Passenger Bryant Magill described a professional scene onboard.

"I'm really impressed with all the flight attendants," Magill told Seattle TV station KOMO. "They kept themselves calm. They kept it professional. There was no panic on the plane."

United spokeswoman Christen David declined to release details about how the crew members realized the pilot was in distress and what their next steps were. The first officer radioed air traffic controllers at 7:55 p.m. to report the aircraft needed to make an emergency landing; the plane was on the ground in Boise by 8:10 p.m., Miller said.

The two doctors and an off-duty United Airlines pilot were among the 161 people aboard the flight. The off-duty pilot aided the first officer -- who is also a trained pilot -- in landing the plane while the physicians performed CPR.

The doctors who helped the pilot were from Madigan Army Medical Center, said Jay Ebbeson, public affairs officer for the hospital at Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

Glenn Harmon, an aerospace physiologist who was an airline pilot for nine years before becoming a professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, said all commercial airline pilots undergo a medical screening every six months to keep their certification with the FAA.

That screening typically includes a test to measure heart function called an EKG, Harmon said, but the test doesn't necessarily pick up every condition.

Sometimes, the in-flight environment can have a small impact on pre-existing medical conditions, Harmon said. The air on a flight is dry, usually at between 10 or 20 percent humidity, and that can contribute to dehydration.

"One thing that happens to us as pilots is we might be dehydrated and not know it," Harmon said. "We don't like to guzzle lots of water because it's so complicated now to get up and leave the cockpit to go to the bathroom."

Sitting in a cramped seating position for long periods can lead to deep vein thrombosis, or clots deep inside the body. Passengers can get up from their seats and move around to help prevent DVT, but pilots don't get the same opportunity, Harmon said.

The cabin pressure also has a slight effect on blood oxygen levels.

Flight crews train for medical emergencies, and most airlines subscribe to a service that puts them in immediate radio contact with a doctor on the ground in case of emergencies. Additionally, all commercial flights have a first officer onboard who is trained to fly the plane in addition to the pilot. There's often a third, off-duty pilot flying to or from work who can help in an emergency.

Even the biggest commercial aircrafts can generally be flown and landed by just one pilot, Harmon said.