As Congress and the White House battle to resolve the nation's debt crisis, a legendary letter written 150 years ago this week by a Civil War soldier on the eve of battle, bidding a heartbreaking farewell to his wife and children, offers a gentle reminder to all Americans of the meaning of sacrifice and love of country.

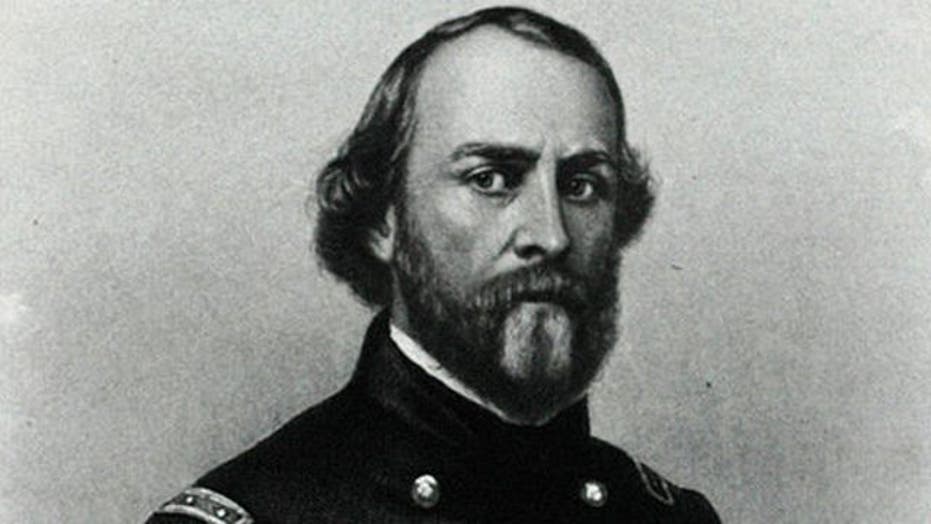

Sullivan Ballou of Rhode Island, just 32 years old but already a major in the Union Army, sat down that calm Sunday night to write his wife, Sarah, before leaving to fight in what would become known as the First Battle of Bull Run.

"Sarah," he wrote, "my love for you is deathless, it seems to bind me in mighty cables that nothing but Omnipotence could break and my love of country comes over me like a strong wind and bears me irresistibly on with all these chains to the battlefield."

Click here to read the full letter.

Now, on July 28, 2011, we remember the 150th anniversary of his death and still, historians say, we have much to learn about the war he fought in, our present situation, and history itself.

Historian Robin Young, author of the book "For Love and Liberty: The Untold Civil War Story of Major Sullivan Ballou and His Famous Love Letter," says Ballou’s words carry more significance today as Congress continues to battle over ways to deal with the nation’s debt problems.

"We are right now looking at a Congress that cannot govern because they cannot compromise and work things out," Young said. "A total breakdown in government led to a civil war being fought. At all costs we need people who can sit down in an adult way a talk through the problems of the nation as Americans."

In his letter Ballou talks of the personal sacrifice he was prepared to make for "pure love of my country."

"I know how strongly American Civilization now leans upon the triumph of the Government, and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution. And I am willing -- perfectly willing -- to lay down all my joys in this life, to help maintain this Government, and to pay that debt."

Young notes that his wife Sarah, would have received the famous letter a couple of weeks after his death. Sarah eventually allowed the local paper to publish the letter in the 1870s. Although the original letter no longer exists, a number of hand written copies have been saved and, Young says, it is likely that Ballou's sons gave their fiancées these copies.

It was already "well recognized for its beauty at the time," she says.

For most people the discovery of the letter came from Ken Burns' PBS Civil War documentary which aired in 1990, in which an abridged version was read. After “The Civil War” aired Ballou’s letter has reportedly been read at weddings, funerals, and memorial services. The companion CD to the documentary which contains a reading of the letter sold thousands of copies and a newspaper that printed transcripts of the letter quickly sold out.

Burns himself admits to still carrying a copy of it in his wallet.

“It’s the most beautiful letter I have ever read,” Burns told the Washington Post. “It’s a Grand Canyon of a letter.”

For Civil War historian Kevin Levin, the letter exemplifies American's perceptions of the Civil War.

"On one hand people are embracing the words of this beautiful letter and on the other hand you have the extreme violence that took place."

Americans like to romanticize history and the war, Levin points out, but we need to deal with the reality as well.

"The glowing words to his wife is what we remember, but on the other side is a very disturbing story."

The First Battle of Bull Run was the bloodiest battle in American history up to that point, with over 3,500 dead or wounded and over 1,000 missing or captured. Levin says it was so bloody a battle that is was where, "innocence was lost."

Maj. Sullivan Ballou fought as a Union soldier with the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment at the First Battle of Bull Run (also known as The First Battle of Manassas).

On the eve of battle, Ballou sat in camp in Washington DC and wrote the, now famous, letter to his wife. The next day he would ride into battle and be mortally wounded when a five pound cannon ball killed his horse. He was taken to the field hospital where his leg was amputated, but had to be left behind when the northern troops were forced to retreat. He died about a week later of his leg wound as a prisoner of war.

His body would later be dug up and desecrated by Confederate troops. He was decapitated and possibly even burned “as an act of revenge,” according to Young, who says that the southern soldiers most likely “mistook his grave for that of the Colonel’s.”

His partial remains were found by a Rhode Island recovery expedition and returned by railroad with great ceremony (“tremendous crowds came and held wakes,” Young said of the train stops along the way) to Rhode Island where he would be buried for the third and final time in Swan Point Cemetery. On his grave is inscribed the last line of his letter to Sarah: “I wait for you there, come to me and lead thither my children.”

The letter that first captured the minds of the late 19th century, remains in the American psyche today and is lasting for its expressions of hope and faith in the face of violence and death. Perhaps it is this sentiment of the human experience that reaches across the centuries to bind us to our ancestors that we relate to today.

“Sarah,” Ballou wrote, “do not mourn me dead, think I am gone and wait for thee, for we shall meet again.”