President to visit community rocked by deadly mudslide

Dan Springer reports from Washington State

As President Obama makes his way to Oso, Wash., to tour the devastation from last month's mudslide and meet with surviving victims and first responders, the disaster has brought renewed interest in early warning systems – which some suggest could have prevented many of the deaths.

At least 41 people were killed and two more remain missing in one of the worst natural disasters in Washington state history. While some have called the half-mile wide hillside collapse an act of God, a growing number of geologists say these tragedies can be anticipated.

"There are tools that we can use to predict landslide behavior, issue warnings of impending failure and, in some cases, predict the time of the failure quite well," University of Utah geologist Jeffrey Moore said.

As evidence, Moore points to a huge copper mine in his home state. Owner Rio Tinto bought the latest landslide detection equipment to protect workers as well as its investment. When monitors picked up movement in April of last year, company officials were alerted. When that flow increased to two inches per day, the decision was made to pull all 300-400 workers out of the mine along with much of the equipment. Nine hours later, the largest non-volcanic landslide in U.S. history struck, sending 165 million cubic feet of earth crashing down. The warning saved lives.

Unlike earthquakes, landslides usually happen over time. Shari Brewer, who has lived near the Oso site for 30 years, noticed the hill was slipping in the days before the disaster.

"We were seeing dirt, and that it was getting bigger," Brewer said. "Before it was just all trees and all of a sudden we were seeing dirt toward the top of the slide. And we were thinking, 'Wow, that's really changed, something is changing up there.'"

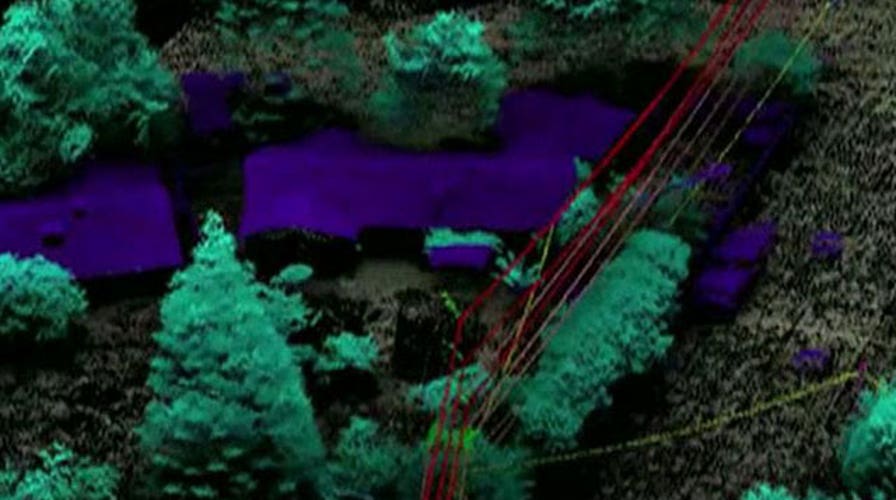

The warning systems run the gamut from low tech to high tech. There are tilt meters that are planted in the ground. LIDAR [Light Detection and Ranging] is a system that uses airborne-mounted lasers to map the most susceptible areas. Commercial satellites and radar are also providing real-time data.

The equipment is being used extensively, not only in the mining and pipeline industries in the U.S., but by governments in Europe. Norway and Switzerland have many people living in landslide zones and have chosen to invest in early warning systems.

All the warning systems, though, have an important limitation. While they can predict when a slide is about to happen, they are not as good at forecasting how far the earth will travel. Even geologists who studied the doomed Oso hillside were surprised by the force and distance of the collapse.

Officials in nearby King County, Wash., are reacting to the Oso slide by updating their landslide hazard map using newer LIDAR technology. But monitoring every unstable hillside where residents might be impacted is cost-prohibitive. The key for them is to identify the slide zones, and then prevent people from building homes there.