Two cancer-combating medicines show potential for protecting U.S. troops and civilians from biological weapon attacks from pathogens like monkeypox.

Just this week, monkeypox was involved in some of the eight cases of possible contact with dangerous biological agents at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick, Md., the Frederick News-Post reported. USAMRIID said last week there were 14 accidents in total involving personnel in full-body protective suits in 2012.

Part of the Department of Defense, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency counters weapons of mass destruction from chemical, biological and radiological through to nuclear and high yield explosive threats. The agency is funding St Louis University’s Mark Buller, who will look at cancer-fighting drugs Gleevec and Tasigna for preventing and treating monkeypox exposure.

The Monkeypox threat

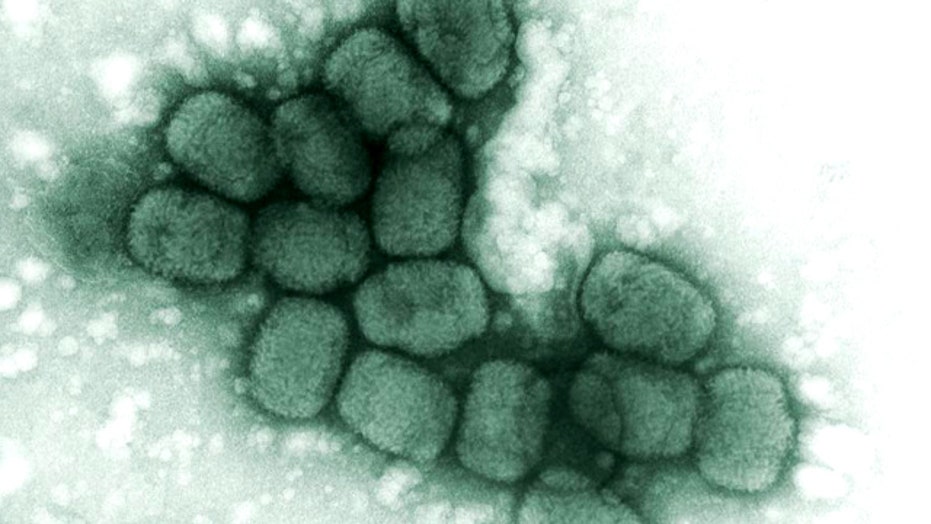

Monkeypox is similar to smallpox. First found in monkeys, the disease was reported in humans for the first time in 1970, but the first U.S. outbreak didn’t occur until ten years ago.

In that outbreak (which is believed to have been unintentional), Americans became sick from contact with infected prairie dogs. The disease can also spread from person to person through face-to-face contact or by touching an infected person’s body fluids or their contaminated objects like clothing or bedding.

Once infected with the virus, symptoms include fever, fatigue, headache, muscle aches, backache and lymph nodes may swell.

While this may sound like an average day with the flu, the telltale sign of monkeypox really is its brutal rash. Often the rash starts on the face and then can spread to the body, becoming raised fluid-filled bumps.

Currently, there is no specific treatment for monkeypox.

Lasting for about a month, monkeypox can be lethal and in some instances has killed about 10 percent of those infected.

The appeal of weaponizing monkeypox to a terrorist is self-evident. There are claims that the Soviet Union achieved weaponization and successful testing.

Are cancer-fighting drugs the solution?

Gleevac, also called imatinib mesylate, is approved by the FDA to treat some types of leukemia and other forms of cancer. Tasigna, or Nilotinib, is also used to treat certain types of leukemia.

Buller’s research will examine key active compounds in these two medicines: Research suggests they could inhibit replication of at least three different viruses. Some believe they have the potential to be broad-spectrum “anti-infectives.”

“They can’t make unique anti-viral medications and vaccines for every potential weapon of mass destruction,” Buller said, instead focusing on “developing broad-spectrum anti-infectives that would be effective against many pathogens.”

Gleevec and Tasigna target the same enzyme that the smallpox and ebola viruses need. Ebola hemorrhagic fever is a highly lethal, severe disease that is also found in both monkeys and humans.

If an infection can be stopped or the spreading of a virus slowed, then it will give the immune system an opportunity to rally and respond with a strong defense.

Throughout the country, other research teams are looking at deploying the very same two cancer drugs against other viruses that could pose a biological warfare threat.