(TRS Inc.)

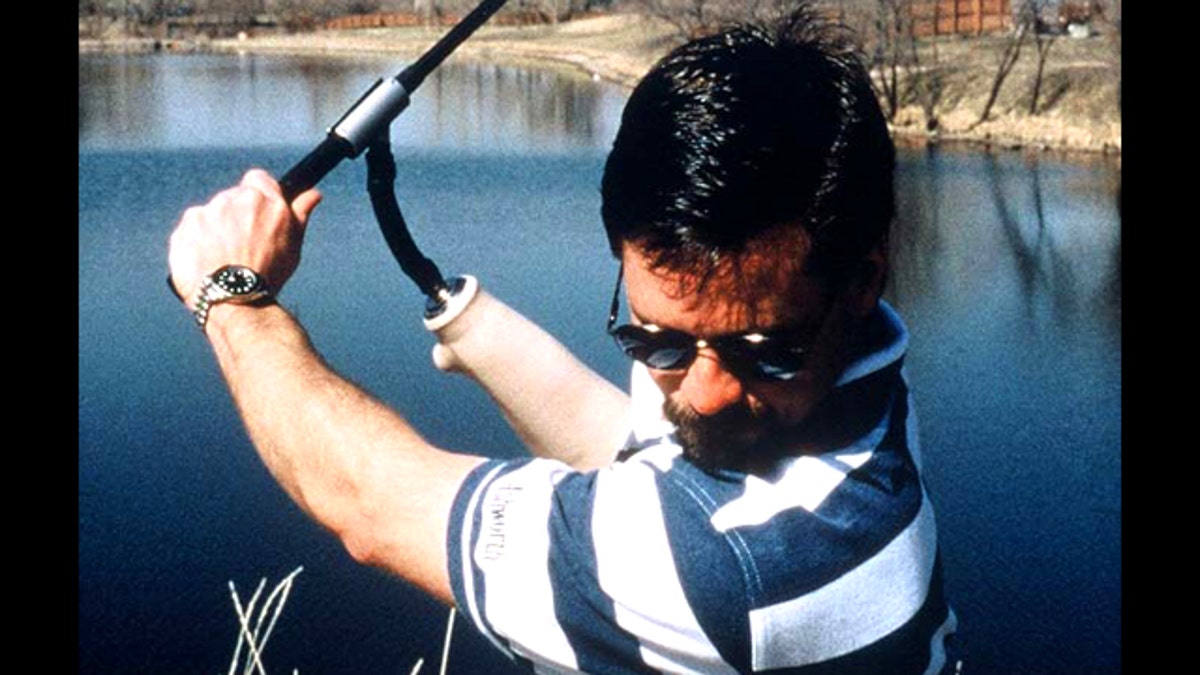

A Florida man who lost his arm 11 years ago now knows what it’s like to swing a golf club.

Researchers at the University of South Florida are studying a one-of-a-kind, golf-specific prosthetic arm, which could allow amputees to hit the links again. It's the first in what the researchers hope will be a fascinating new field: sport-specific prosthetic limbs.

“Can these people muster a reasonable swing sufficient to enjoy recreational participation in golf?” asked Jason Highsmith, assistant professor in the USF School of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Sciences. So far, yes. And there's more good news: The amputees also showed they could play using the prosthesis without much training.

Studies like this bode well for a potentially gigantic new market, making sport-specific prosthetics biomechanically effective for long-term use. TRS, the company behind the golf attachment, has designed a number of sport prostheses, including a mesh net that screws into the socket of a player’s existing prosthetic limb for baseball -- not to mention a bat attachment similar to the golf devices.

It could bring the joy of baseball to people who currently have no way to play.

Highsmith says researchers are creating a database detailing what amputees can do with this type of upper-limb device. A previous study had looked at a prosthesis for kayaking.

First-time golfer Alan Hines, an amputee who participated in the study, said he felt comfortable using the prosthetic device. “I didn’t think I would do well,” he said.

The prosthesis, called the Eagle Golf TD, consists of a just-over-6-inch chunk of plastic and metal that screws into the socket of an existing prosthetic limb. The thinnest part of a golf club -- the stem -- easily slips within the shaft of the Eagle Golf, which slides up the golf club to clamp securely to its fat grip. This gives the player a strong handle on the golf club for a very natural motion.

Hines, who had never played golf before, swung it with the ease of a natural. Two models offer slightly different features: The Eagle Golf TD allows amputees to have a firmer grip, while the Golf Pro, a longer device with a movable extension, allows players wrist-like rotation. Hines’ favorite: the Eagle Golf TD.

“I didn’t think I could play a sport,” said Hines, who lost part of his right arm after suffering a dramatic shock while working for a power company in 1999.

Other devices, such as sophisticated and costly bionic arms, don’t unlock a person's full potential, said TRS President Bob Radocy.

“It doesn’t have the range of motion,” Radocy explained, arguing that his prosthetics can better enable an amputee. Amputees liked not having to control the wrist, Highsmith pointed out. Stephanie Carey agreed. The research coordinator for USF’s Center for Assistive Rehabilitation Robotics Technology noted that amputees have a limited degree of freedom, unlocked by this device.

Researchers have yet to analyze all the data, but so far the study shows that the head speed of an amputee player's club is somewhat slower than the swing of a non-amputee. Head speed measures how fast a player can drive the ball, and the highest an amputee in the study could reach was 95 feet per second, compared with 121 for a non-amputee volunteer.

But what if that improves -- and what if the technology matures, bringing firmer grips, more torque, and greater head speeds than what non-handicapped golfers can achieve? In some professional sports, athletes who use prostheses are not allowed to compete against non-amputees, due to fears about performance advantages.

In one notable case, the International Association of Athletics Federations questioned whether a South African sprinter with specially designed artificial feet could compete in the 2008 Olympics. The court of appeals ruled him eligible, but Oscar Pistorius ultimately failed to quality.

According to the United States Golf Association's rules for amputee players, artificial devices must not give the player “any undue advantage over other players.” Radocy said that his prosthetics do not.

“It brings a person up to the equivalent of someone with two arms … they allow people to be as good as they can be, and that’s the important thing,” he said.

The research is part of a larger study funded by a Department of Defense grant that examines how amputees can better accomplish daily tasks, such as opening a door. Highsmith said the need for this type of research is growing.

“It’s not been a big enough problem in the past where people have really wanted to make a niche doing it," he told FoxNews.com. "But here we are now with folks coming back from the war … it’s recognized that these folks are going to need some options,” he said.

Another long-term goal, Carey said, is to create a program that can assess the amount of muscle an amputee has left over to predict how he may move with a certain type of prosthesis and enable doctors to accurately match patients with prostheses.

“The next layer for us is to tease this [data] apart and use it for other Alans across the country,” Highsmith said.

Hines’ 14-year-old son, Shane, said “it’s going to be pretty cool” to play golf with his dad.

“We'll have to play and see how bad he can beat me,” Hines said with a laugh.