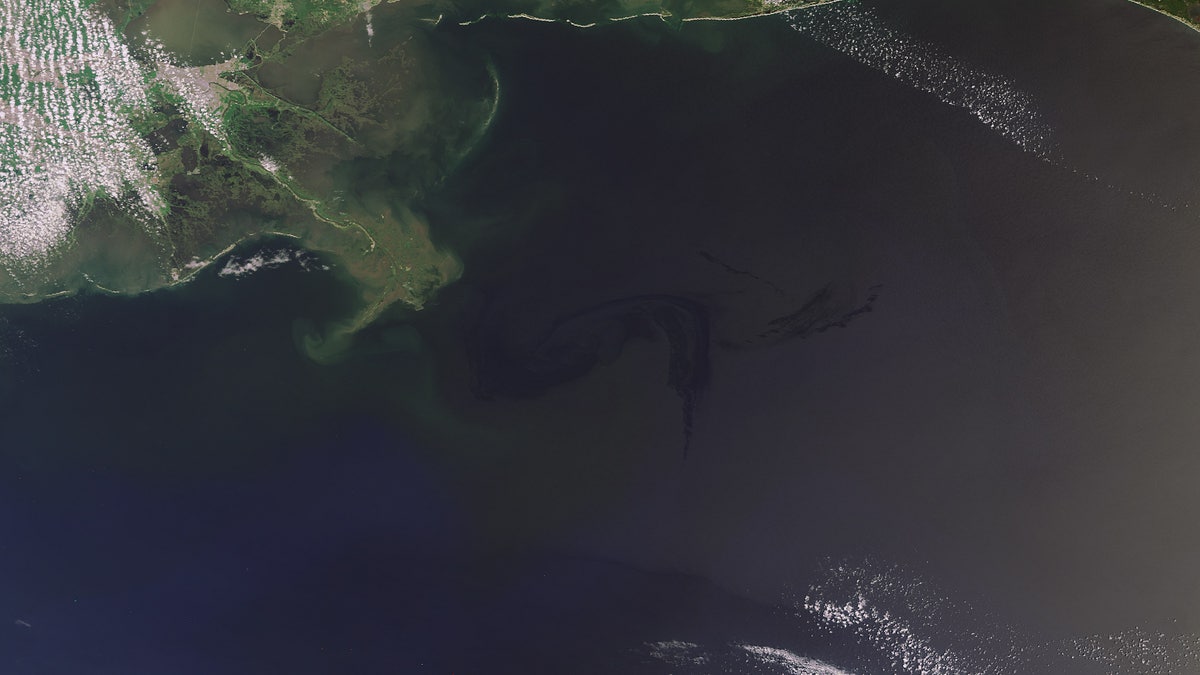

(ESA)

As oil from the gigantic spill in the Gulf of Mexico reaches U.S. beaches, scientists warn that the potential long-term effects of the massive disaster are hard to gauge -- but potentially disastrous for some local species.

The Exxon Valdez disaster is a similar and telling example. Among the worst oil spills ever, the tanker dumped more than 10 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska's Prince William Sound in March 1989. Two decades later, there are still an estimated 21,000 gallons of that oil just below the surface.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently dug 9,000 holes over hundreds of miles of shoreline to ascertain just how much oil was still hanging around. NOAA found Valdez oil in about half of those holes.

"Despite spending $2 billion dollars and using every known clean-up method there was, they recovered 8 percent of the spilled Exxon Valdez oil," Jeffrey Short, Pacific science director for Washington, D.C. conservation organization Oceana told LiveScience. "That is typical of these exercises when you have a large marine oil spill. You're doing really great if you [get] 20 percent."

Yet despite the lingering oil, many local species recovered: 10 recovered completely, 19 are still recovering, and only two never came back, including the local herring.

Scientists at the University of California-Davis, which manages California's Oiled Wildlife Care Network, point out that should the oil hit shore, it could have a serious, long-term impact on marine seabirds, such as brown pelicans. The Mississippi Flyway is a critical thoroughfare for migratory birds, and is now experiencing its peak migratory period, said Michael Ziccardi, an associate professor of clinical wildlife health at the UC Davis Wildlife Health Center and director of the Oiled Wildlife Care Network.

Data is limited on the long term effects of oil on wildlife, but Ziccardi pointed out that after the Valdez disaster, two killer whale pods lost approximately 40 percent of their numbers. Since that time, the reproductive capacity of these pods has been reduced by the loss of females, and only about half of newborn calves are surviving.

George Crozier, executive director of the Dauphin Island Sea Lab, worried about the potential long term effect on coastal marsh lands as well.

"If they let it come into the passes, and if they don't protect the marshes, it will cause long-term economic loss for years, because there's no way to clean it," he said. "They can talk about spraying micro-organisms on the marsh that may help it recover a little faster, but you can't spray grass beds and oyster reefs."

"It's an accepted fact that the marshes of Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama -- the Fertile Crescent -- produce 90 percent of the seafood in the Gulf of Mexico," Crozier told the Mississippi Press. "If you were to pave that over with an oil spill, you'd see a dramatic drop in seafood recruitment, possibly for years to come."

As authorities and BP work frantically to clear up the oil and prevent further from leaking, the question of how long it will remain in the environment becomes a factor in determining the oil's long-term effect. Oil that doesn't get skimmed up or burned off disperses naturally, according to U.S. Coast Guard Petty Officer 3rd Class Cory Mendenhall. He told LiveScience that "It eventually breaks up and evaporates. There are different ways, but we're told it just kind of goes away."

The rate of dispersal depends on the type of oil. Initial reports suggested the oil leaking into the Gulf was standard Louisiana crude, which biodegrades pretty well, according to Edward Overton, a professor emeritus of environmental sciences at Louisiana State University. But sample testing revealed that the leaking oil was different, with a very high concentration of components that don't degrade easily, called asphaltenes.

"That is bad, bad news, because this oil is going to be very slow to degrade," Overton said.