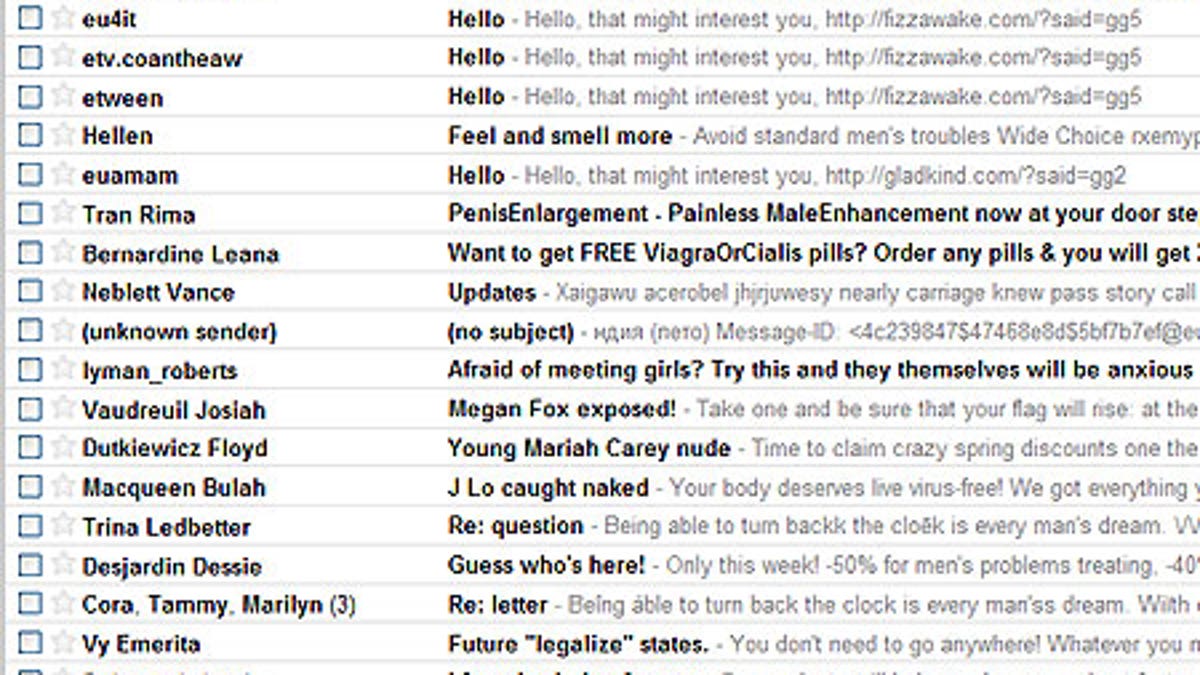

A screen shot of spam piling up in a Gmail account. (Google)

Spammers come in all shapes and sizes. One in particular wears very large sneakers.

Bill Bradley -- Basketball Hall-of-Famer, Rhodes scholar, former U.S. senator from New Jersey and onetime presidential candidate -- may very well be helping to clog up your inbox with unwanted mail.

Bradley sits on the board of QuinStreet, which is identified as a major spamming firm by anti-spam organizations such as www.stop-spam.org and www.spamsuite.com.

Founded in 1999, the California-based QuinStreet lists over 200 employees and posted revenues of nearly $8 million last year. Its clients include ADT home security systems, DeVry University, dating Web sites, video-game publishers and credit-card companies.

It describes itself on its Web site as a "leader in vertical performance marketing and media." Internet security experts say companies that label themselves vertical marketing companies, Internet advertising firms or e-mail reputation services could be using code words for something very annoying -- and possibly illegal.

"There's a class of company called 'affiliates,' and they're basically organizations that send spam for some other company that holds the product," said Adam O'Donnell, Director of Emerging Technologies at Cloudmark Inc., an Internet security firm. "Think of it as a third-party marketing firm that does the dirty work of sending spam."

This acts as a shield, making e-mail traces more difficult.

"Spam is such a dirty thing at this point, they try to isolate it under shell companies and separate it from the core of their business, because if they get caught, it would be a PR nightmare," said O'Donnell.

Bradley -- who also sits on the boards of Seagate Technology, Starbucks Coffee Company and Willis Group Holdings Ltd. -- was appointed to QuinStreet's board in 2004. It is not known whether Bradley receives income from the company.

At the time, he said he was drawn to the QuinStreet because of its values of "integrity and oversight in supporting public confidence in American business."

• Click here to visit FOXNews.com's Cybersecurity Center.

• Got tech questions? Ask our experts at FoxNews.com's Tech Q&A.

But some Internet users, whose e-mail addresses have found their way to the company's virtual Rolodex, say QuinStreet uses aggressive spamming tactics.

"What drives me the most crazy about this network is that they act as if each of the e-mails is from the individual [companies]," one victim told FOXNews.com.

Internet security experts say companies like QuinStreet could very well be breaking the law.

In 2003, the Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography and Marketing Act, or CAN-SPAM Act, made it a federal crime for companies to send mass, unwanted e-mails to consumers.

Those prosecuted can be fined up to $11,000 per violation. The CAN-SPAM Act also mandates that there be an "unsubscribe" option for all solicitation and advertising e-mails.

One e-mailer told FOXNews.com that the solicitations from QuinStreet kept filling his inbox even after he requested to be taken off their list.

While the Better Business Bureau has registered only two complaints for QuinStreet under advertising and sales practices (and several more in other categories), other complaints have been filed under QuinStreet's aliases — such as VendorSeek.

In 2007 Washington state resident Mark Ferguson tried unsuccessfully to sue QuinStreet for filling his and his client's mailbox with spam.

Neither Bradley nor QuinStreet responded to repeated requests for comment. Another board member, John G. McDonald, professor of finance at the Stanford University School of Business, refused to comment, saying only, "My students are my first priority."

Spamming is a large and growing problem, according to Symantec, a Fortune 500 company that provides Internet security to consumers and corporations. It said 349.6 billion spam messages were sent worldwide last year -- up 192 percent from the 119.6 billion sent in 2007.

So how do these companies get your name? Most commonly, if you purchase something online from a non-reputable firm — for example, one you found through a spam e-mail — that company will add your address to a list that it then sells to other companies.

"Your e-mail address is going to get sold, and resold, and resold, and resold, and eventually you get passed up the way into something that's sort of legitimate — it's kind of like money laundering," says Ryan Singel, a staff writer with Wired.com who has been covering Internet security issues for years.

Another way to get on such a list is by replying to a spam mail sent by a firm that sends e-mail blasts to random names in hopes of landing on some legitimate addresses.

Singel says getting your name off a spam list can be near impossible.

"So it can be very difficult, from those marketers, to stop those e-mails, because once your e-mail is in there, it passes around so much that you opt out of one place, but you get spam from five other places."

Consumers often feel they can't do much besides complaining to the Federal Trade Commission or Better Business Bureau, but there have been some legal successes.

In 2008, online advertiser ValueClick, Inc., and its subsidiaries, E-Babylon and Hi-Speed Media, were forced to pay a $2.9 million settlement for breaking CAN-SPAM Act laws.

The FTC charged that the companies were offering free iPods, laptops and game consoles to customers who filled out surveys — prizes that never materialized.

World-famous spammer Robert Soloway, who ran a company called Newport Internet Marketing, was arrested in 2007 and later sentenced to 47 months in federal prison for his spam and mail-fraud crimes.

Unlike the more "respectable" spam companies, Soloway was charged in connection with accusations that he faked return addresses on the e-mails he sent out, and that he used computer viruses to infect random consumers' PCs with programs that sent out even more spam.

The government dropped most of the charges against Soloway in a plea deal.

Back in 2003, Microsoft sued Soloway for spamming, and won. Soloway was ordered to pay Microsoft $7 million in damages, but so far, Microsoft has been unable to collect the money.

Internet security experts admit that while they continue to win some of the spam battles, they acknowledge that they're not winning the war.

"Every day there's going to be a little bit that leaks through — it doesn't matter what kind of spam system it is," says O'Donnell. "I mean, otherwise spam would be solved by now."