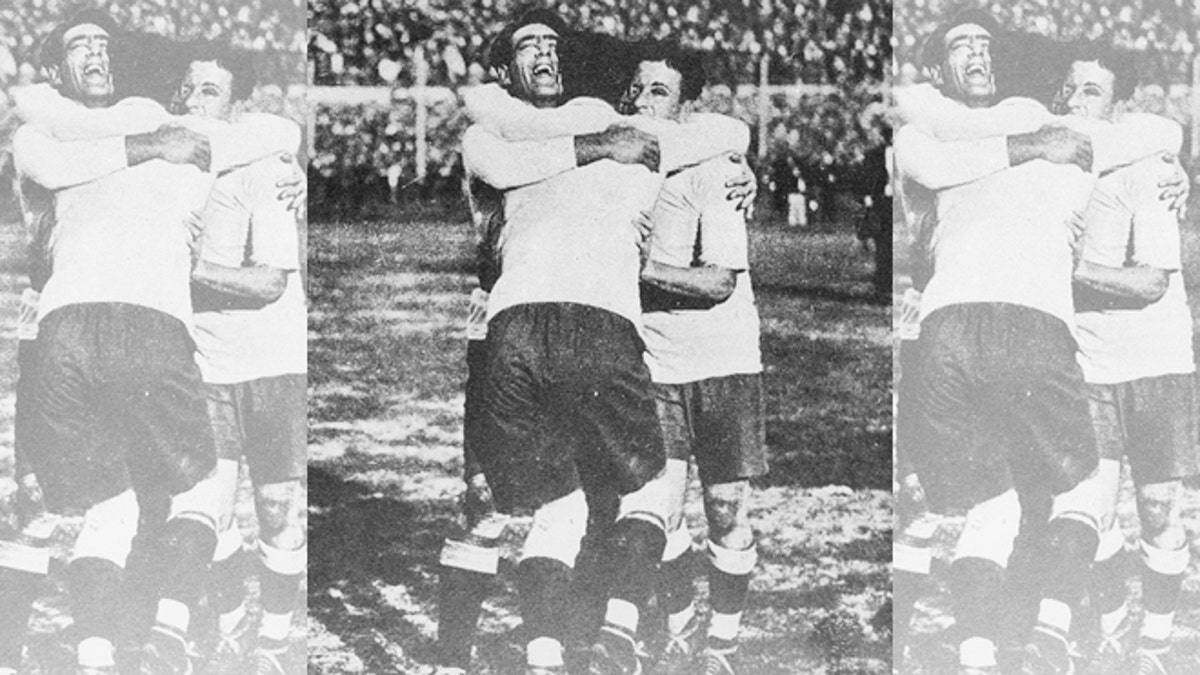

Lorenzo Fernandez, Pedro Cea and Hector Scarone of the Uruguayan national team celebrating winning the first World Cup in 1930 in Montevideo. (Getty Images)

They were meat packers and ice salesmen, marble cutters and carnival musicians. Most came from Italian stock and bore names like Nasazzi, Scarone and Petrone. One, José Leandro Andrade, was the son of a 98-year-old runaway Brazilian slave who was said to have magic abilities.

Most were born penniless, and many of them died that way, too. But together, over the course of seven years, they would revolutionize soccer and dominate the game at its highest stages.

The beginning, as beginnings usually are, were humble.

The Uruguayan team, whose core players were all 25 or younger, qualified for the 1924 Olympics by beating archrival Argentina in the South American Championship. Back then, few nations bothered to spend the money for trans-Atlantic trips for their athletes, so when Los Celestes took third-class steerage to Europe and played a series of exhibition matches in Spain (winning all nine), it was the first time any Europeans had witnessed a South American squad in action.

In many ways, the soccer landscape still shows the marks of those dynastic Uruguayan squads. It isn’t an overstatement to suggest that what we think of today as the Spanish and French style of play was modeled on that of the 1924 Uruguayan team.

And the Uruguayans were a sight to behold. They played a brand of soccer unknown in the Old World—a ball-controlling game with quick passes and long runs up the field that put shame to the long-ball and aerial game that was prevalent at the time.

Los Celestes were spectacularly successful, winning all five Olympic matches they played by an aggregate score of 20-2.

The captain was José Nasazzi, a granite-tough fullback who appropriately enough had been a marble cutter. On being told that the team would be heading to the Olympics, he supposedly threw down his tools and said, “Never again will I hold you.”

Their front line was fearsome, with Pedro “Artillero” Petrone in the center, flanked by Héctor Scarone and Pedro Cea (who contributed six, five and three goals, respectively, of the aforementioned 20).

But the biggest star was Andrade, a midfielder who wowed the crowds with his artistic dribbling and precise body control. Off the field, he took to boulevardier attire and became something of a dandy. The Parisians loved him—or fetishized him, maybe. In Uruguay he was known as La Perla Negra; the French dubbed him the Black Marvel.

Not that Andrade was always serious. The Uruguayos practiced dribbling in overlapping figure eights they called moñas. According to historian Eduardo Galeano, when Andrade was asked about the moñas by a journalist at the Olympics, he answered that they had started the practice by chasing chickens.

In the final, which 60,000 people watched, Andrade and company dismantled the Swiss, 3-0. The French journalist Gabriele Hanot described the action this way:

The Uruguayans are supple disciples of the spirit of fitness rather than geometry. They have pushed towards perfection the art of the feint and swerve and the dodge but they also know how to play directly and quickly. They are not only ball jugglers. They created a beautiful soccer, elegant but at the same time varied, rapid, powerful, effective. Before these fine athletes, who are to the English professionals like Arab thoroughbreds next to farm horses, the Swiss were disconcerted.

In Montevideo, the news prompted celebrations and the declaration of a national holiday. The squad returned home heroes; but in Argentina, there was much tooth gnashing at the Celestes’ accomplishments. A home-and-away, unofficial South American championship was organized.

After a 1-1 tie in Montevideo, the Buenos Aires match was marred by fans throwing stones at Andrade. Down 2-1, the Uruguayans started throwing the stones back. Police stormed the field. Scarone kicked an officer and got arrested—the rest of the team abandoned the game and the Argentines declared themselves the victors.

When the time came for the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam, neither the Uruguayans nor the Argentines were about to miss it. Inevitably, the archrivals faced off against one another with the gold medal on the line. On June 10, they played 120 minutes to a 1-1 tie with Petrone scoring the lone Celeste goal. Three days later, they tried to settle the matter again; this time, Scarone broke a 1–1 tie in the 73rd minute off a corner kick.

The second gold medal had come at a cost: Andrade slammed into a goal post during the semifinal match against Italy and injured his eye badly enough that his vision was permanently impaired. Despite occasional flashes of brilliance, he would never again be the superstar he had been.

When FIFA representatives got together in Barcelona the following year to determine the site of an international soccer competition scheduled for 1930, various countries vied for the opportunity to play host. The Argentinian representative—the Argentinian!—enumerated the reasons the honor should go to Uruguay, No. 1 being “the excellent results obtained by that country in the last Olympiads.”

And so it happened that two rivals faced off once more in the championship match of the first World Cup at the brand new Estadio Centenario in Montevideo in front of some 93,000 vocal fans. This time the Argentinians would take a 2-1 lead at halftime, but the Celestes stormed back, with Pedro Cea leading the charge, to win 4-2.

The IOC and FIFA—two bloated sports bureaucracies – have been dominated from their beginnings by the Europeans and have sunk to the depths of cronyism and corruption.

But the World Cup, unlike the Olympics, has been hosted many times in Latin America, Africa and Asia—a distinction that may be the most enduring legacy of Srs. Andrade, Petrone, Scarone, Cea and Nasazzi.