So much happened in the 1992 Hooters 500, that year’s huge season-ending Sprint Cup race, that it is difficult to form a catalog.

Alan Kulwicki completed the winning of an unlikely championship with an “independent” team that was skeletal compared to the big guns of the day.

Jeff Gordon, a young driver with much promise who would go on to transform the sport, made his Cup debut. He finished 31st and was virtually unnoticed in the electricity of the day.

It was Bill Elliott’s last real hurrah. He won the race but lost the championship when Kulwicki outsmarted the more monied, more experienced Junior Johnson team, leading one more lap than Elliott to win the title on that bonus.

It was Davey Allison’s last shot – although no one knew it then – at the first of what many observers figured would be several championships for the very talented and hard-driven older son of former superstar Bobby Allison. Allison crashed with Ernie Irvan and finished third – to Kulwicki and Elliott – in the championship race. The next summer, Allison died in a helicopter crash, three months after Kulwicki was killed in a plane crash.

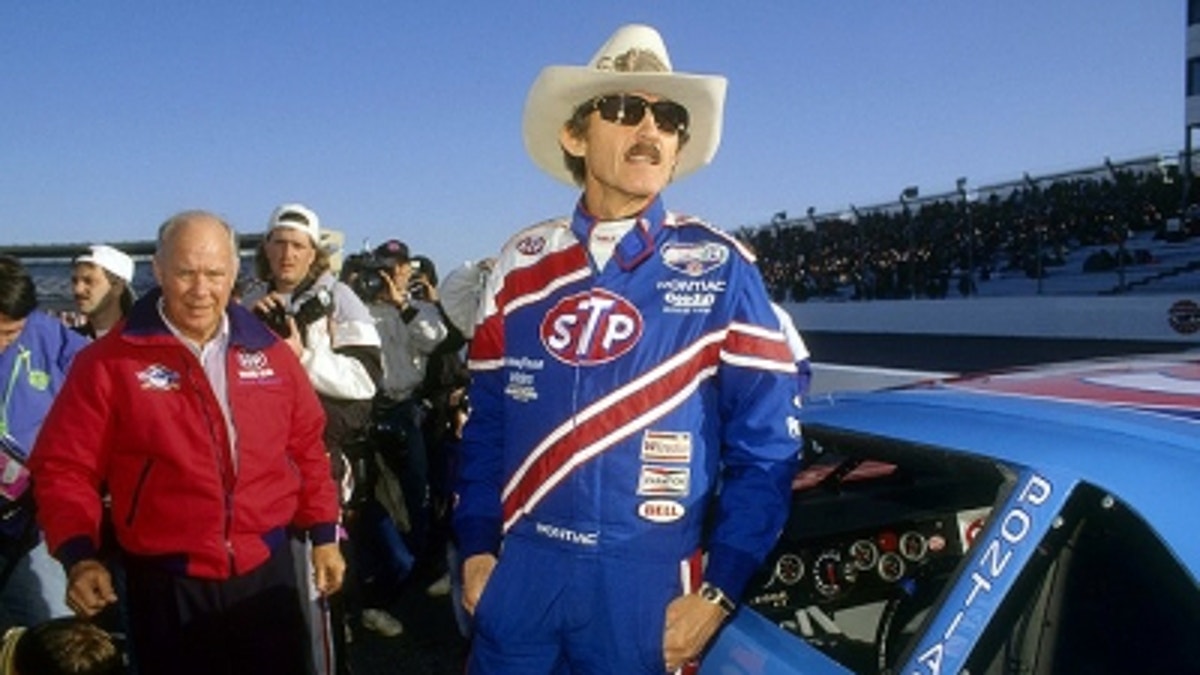

Despite the other events of that November day at Atlanta Motor Speedway – now, incredibly, almost 20 years ago – the big one was the retirement of Richard Petty, a driver who had defined his sport in much the same way Arnold Palmer defined his and Johnny Unitas defined his.

For so many years, Petty was the bright, shining face of NASCAR, his piano-key smile and overflowing personality – not to mention his rock-solid driving talent – carrying the sport through its developmental years and onto the national stage.

And now it was all coming to a close. For the relatively small group of journalists who had been on the Petty Watch for much of the North Carolina driver’s career, it was a day awash with memories, emotion and – in no small way – trepidation.

Atlanta was – and is – a dangerous race track, and, although we had seen Petty survive spectacular crashes at Daytona, Pocono and Darlington and smaller waystations along the NASCAR trail, there always was the fear that the sport’s grandest icon could become the victim of a crash that would leave him mangled – or worse.

We had seen him climb from race cars over the long, last years of his career, looking like a ghost of the man who once ruled his sport, his body wracked by decades of racing, numerous crashes that left him with broken bones and stomach surgery that had significantly impacted his already-thin body.

There was a line of people relatively close to Petty who pushed forth the opinion over his final years that it was past time – past time for Petty to quit driving and ease into whatever the next part of his career held.

He had not won since the magic of 1984, when he beat old foe Cale Yarborough in a wild battle to the finish in that Daytona summer. That was the landmark 200th career victory, and it was like Petty had waited for that moment to begin the long slide toward irrelevancy.

Like some other winning drivers, he held on too long as he chased the dream and cashed the checks.

But, despite the struggles and with all the grace he had shown through all those great seasons, he carried the fans along for one last ride, leading what he called the Fan Appreciation Tour and accepting the accolades of his adoring army throughout the 1992 season.

Finally, the very end came in the unfortunately named Hooters 500. The last race for a king should have carried a more regal name, but Petty understood the importance of sponsors more than most, so that was never an issue.

Still, the artwork of Petty waving farewell on the speedway’s race-day program under the word “Hooters” was a bit unsettling.

As if the day didn’t carry enough raw emotion, Petty started it by addressing the other drivers at his final drivers meeting and giving each one in the starting field a special token in observance of his last race. Drivers are given stuff all the time, but it’s safe to say that Petty’s gift carried special meaning for those in attendance.

“I'm very proud I was able to be a part of it,” Gordon said. “Here is a legend of our sport that will never be topped – nobody is ever going to win 200 races, yet I was able to be a part of a fairly intimate setting and hear him speak at that drivers meeting of what his career meant to him, how much he appreciated so many things and the fans and the competitors. That was very, very cool to be a part of that.”

As the high drama of the race unfolded – with several drivers in the mix for the win and the championship, Petty ran mid-pack. Then, on lap 96, he was caught up in a multi-car crash and wound up limping off the track inside the first turn, his red and blue car damaged and aflame.

Some hearts skipped a few beats. It would be the most difficult of ironies – Petty hurt, burned, battered in his last ride.

He climbed out of the car quickly, though, and the fire was extinguished rapidly. Petty waved to the crowd – a final wave, most thought, and there was a perceptible sense of relief in the sellout crowd and – yes – in the press box.

Turns out it wasn’t exactly Petty’s valedictory, however. His crew jumped on his mangled race car and repaired much of the damage. Petty had assumed his last day was at an end, but he was summoned to the garage for more work.

Richard Petty’s final race would end with the King on the race track, after all. The crew restored the racer with that single thought in mind, and Petty took the checkered flag on the asphalt, rolling through turn four and under the flagstand one final time.

Later, using the Petty charm that remains a hallmark of his personality to this day, he explained that he had wanted to go out in “a blaze of glory, not a blaze.”

The season was over, as was Petty’s career – after 1,184 drives.

The cheering for Kulwicki, a longshot champion who had done it “his way,” rang out long into the night.

The Petty crew packed up the Last Race Car and headed back to North Carolina.

When first light broke the morning after the race, it was a new day.

Mike Hembree is NASCAR Editor for SPEED.com and has been covering motorsports for 30 years. He is a six-time winner of the National Motorsports Press Association Writer of the Year Award.