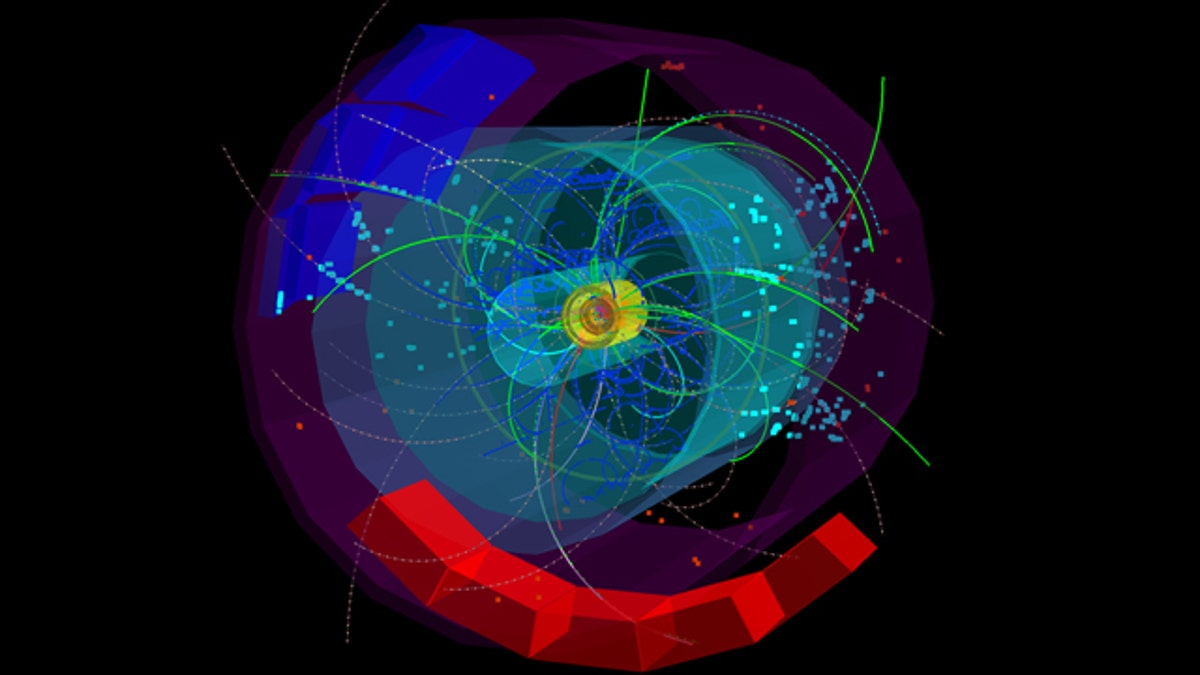

Particle tracks fly out from the heart of the one of the first collisions in the Large Hadron Collider at a total energy of 7 TeV. (Despina Chatzifotiadou / CERN)

Scientists working with particle accelerators in Europe and the United States said on Monday they may be closing in on the elusive Higgs Boson, the "God particle" believed crucial to forming the cosmos after the Big Bang.

Researchers from the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) project near Geneva said in just three months of experiments they had already detected all the particles at the heart of our current understanding of physics, the Standard Model.

Rolf Heuer, director-general of the European Center for Nuclear Research (CERN) which runs the LHC, told the International Conference on High Energy Physics in Paris experiments were progressing faster than expected and entering a stage in which "new physics" would emerge.

This could include long-awaited proof of the existence of the Higgs Boson and the detection of dark matter, believed to make up about a quarter of the universe alongside an observable 5 percent and 70 percent consisting of invisible dark energy.

"This is a dark universe and I hope the LHC ... will shed the first light into this dark universe," Heuer told the international conference. "This will take time."

The LHC, a 27-km (17-mile) looped tunnel which creates mini-Big Bangs by smashing together particles, is currently colliding particles at around half its maximum energy level -- 7 million electron volts, or 7 TeV.

It plans to increase this to 14 TeV from 2013, coming closer to the conditions in which the universe was created 13.7 billion years ago.

"Whether the LHC will have discoveries by 2012, I don't know. I hope it might happen, but if it doesn't happen then it might be three or four years later," Heuer said.

U.S. PROJECT

Scientists at the older, lower-energy Tevatron particle accelerator near Chicago told the conference they had narrowed the range of possible mass for the Higgs Boson by around a quarter, with 95 percent reliability.

However, they are still not capable of reaching the low-mass region which many people believe is home to the Higgs -- a theoretical energy particle which many scientists believe helped give mass to the disparate matter spawned by the Big Bang.

Presenting results from the $10 billion LHC project, scientists said they believed they had detected for the first time in Europe the Top Quark -- a massive, short-lived particle previously only identified in the United States.

"From now on, we are in new territory," said Oliver Buchmueller, a senior CERN researcher. "What we are doing is effectively going back in time. The higher we raise the energy, the closer we come to what was happening at the Big Bang."

The LHC is due to continue operating until 2030, but discussion of the next phase of experimental facilities has already begun.

Two rival projects, the International Linear Collider (ILC) and the Compact Linear Collider (CLIC), are being considered to usher in a new era of high energy physics by smashing sub-atomic particles together in straight lines of up to 50 km.

However, Heuer said some of the technology needed for the more powerful CLIC collider had not yet been developed, and the exact details of any future project would depend on what was discovered at the LHC in the coming years.

No site has been identified for a linear collider and its location would probably depend on which countries were willing to fund much of the estimated cost of more than $10 billion, he said.