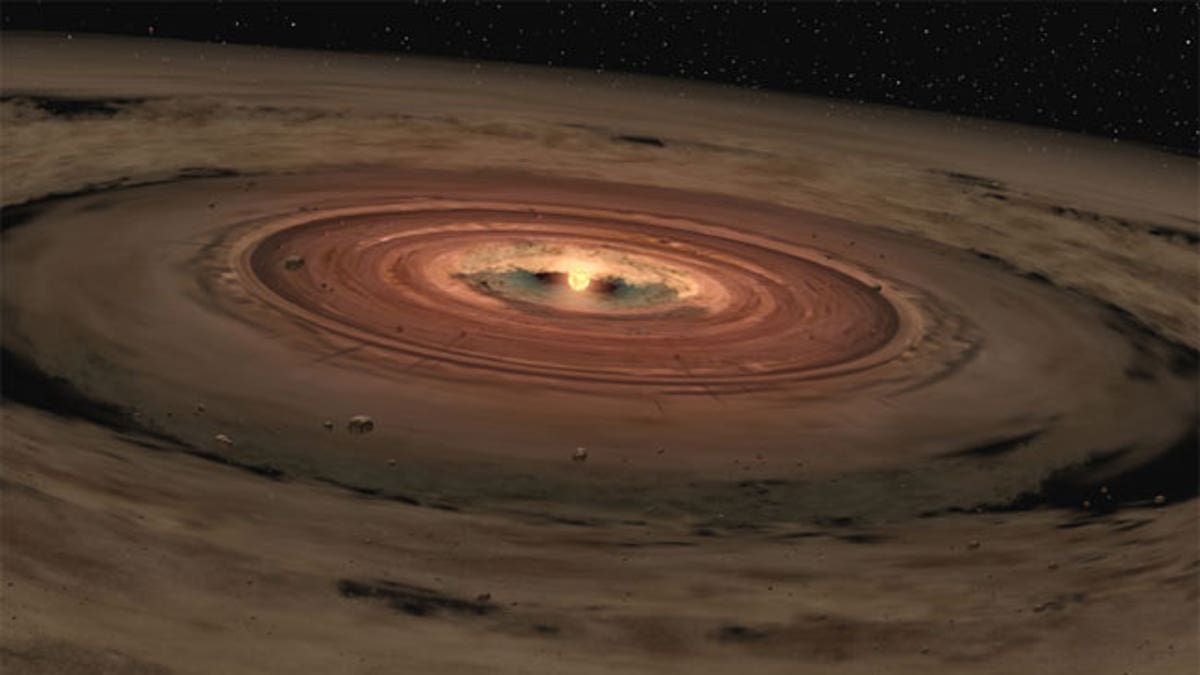

This artist's illustration shows a very young star surrounded by a disk of gas and dust, the raw materials from which rocky planets such as Earth form. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The water sloshing in Earth's oceans and coursing through its canyons may have been with the planet since it first started taking shape, new research suggests.

The origin of Earth's water has long been a topic of considerable discussion and debate. Some scientists hold that the wet stuff is mostly primordial, dating back to the mountain-size building blocks that coalesced to form our planetabout 4.5 billion years ago.

But others think Earth was born very dry and that it took sustained bombardment by sopping-wet asteroids and comets long ago to dampen the planet to its present state. (By the way, modern-day Earth isn't as soggy as you may think: Though water covers 70 percent of Earth's surface, the stuff makes up just 0.05 percent or so of our planet's mass.) [Earth Quiz: Do You Really Know Your Planet?]

The new results should hearten the primordialists. In two new modeling studies, researchers determined that tiny grains of dust swirling around the newborn sun in the region where Earth eventually formed could have held enough water to explain the amount on the planet today.

More From Space.com

And these grains could have snagged the requisite water from their surroundings in just 1 million years or so, the scientists found. That's quickly enough that the planet-building boulders — which themselves grew from clumping dust grains — could have been wet enough as well. (If it took longer for the dust to slurp up water than it took for the boulders to form, then it doesn't matter how wet the grains could get — Earth would still form dry.)

The two new studies don't represent the last word on the origin of Earth's water, of course; the debate will doubtless continue as scientists conduct additional modeling studies and look at more and more evidence gathered from meteorites on the ground and comets and asteroids in space.

And researchers will soon be able to examine two different examples of pristine asteroid material in their labs in here on Earth, if all goes according to plan. Japan's Hayabusa2 spacecraft and NASA's OSIRIS-REx probe are scheduled to return samples of the asteroids Ryugu and Bennu to Earth in 2020 and 2023, respectively.

The two new studies were both submitted to the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. One has been accepted for publication; you can read it for free at the preprint site arXiv.org.

Originally published on Space.com.