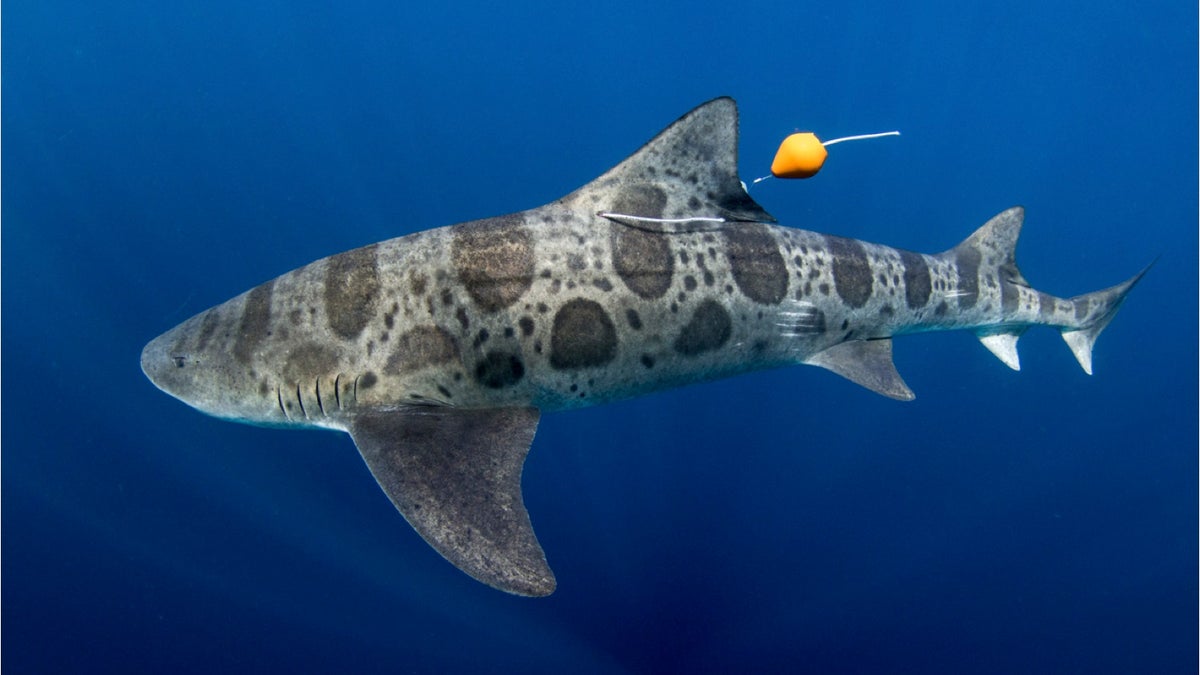

This is a shark with a reusable tagging apparatus. (Kyle McBurnie)

One of the great mysteries with sharks has been how they manage to navigate a straight path between distant locations in the ocean.

It turns out some may be using their noses to point the way – or least their keen sense of smell that is so critical for hunting down prey.

A new study in PLOS ONE published Wednesday concluded that olfaction appears to contribute to shark ocean navigation, possibly based on their ability to sense chemical changes in the water as they swim. It’s the first time that smell has been singled out, though it was hypothesized before with sharks and other species including birds and turtles.

Related: Scientists discover shark nursery in New York waters

“We’ve known for a long time that sharks are capable of long distances migration. They travel long distances along fairly straight paths," Andrew Nosal, a post-doctoral researcher at Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Birch Aquarium, told FoxNews.com . “That begged the question: how exactly do they do it? What sorts of cues do they use to find their way?”

To test their theory on smell, Nosal and his colleagues captured 26 leopard sharks off La Jolla, California and transported them about 6 miles off shore. Half had their sense of smell temporarily impaired – putting a cotton ball soaked in petroleum jelly in their nostril-like nares – and then they were released with acoustic trackers attached.

Related: Tiny shark that glows discovered in the deep ocean

To ensure the captured sharks didn’t pick up any hints along the way, the researchers blocked visual cues by covering the holding tank with a tarp, neutralizing geomagnetic cues by placing a strong magnet over the tank and minimizing any chemical cues by aerating the water from a scuba tank, rather than from the offshore atmosphere.

Leopard shark just after release offshore. (Kyle McBurnie)

“We wanted to kind of confuse the sharks. We didn’t want the sharks retracing their steps and finding their way back,” Nosal said, adding they even conducted several figure 8 maneuvers on their way out to the open ocean and released the sharks in random directions.

On average, the sharks with no impairment ended up 62.6 percent closer to shore after the four hour period and followed relatively straight paths. In contrast, sharks with an impaired sense of smell ended up only 37.2 percent closer to shore and did it by following more tortuous paths.

“Even the sharks that we released in the offshore direction, they started to swim offshore initially. Within 30 minutes, they made a corrective U-turn and just bee lined it back to shore. They made it quite close to shore," Nosal said. "The ones who couldn’t smell, they didn’t make as closer to shore and the paths they took were more windy.”

Related: NOAA: Historic number of sharks found off East Coast

The fact, though, that some of the impaired sharks made it back to shore suggests other cues could be helping sharks find their way home. Among them could be acoustic cues such as the low-frequency sounds of waves crashing on shore or geomagnetic cues that are also used by turtles as guidance.

Andrew Nosal releasing a leopard shark. (Kyle McBurnie)

“Their movements were still biased towards shore. They still ended closer to shore than when they started,” he said of the impaired sharks. “What that suggests is that olfaction participates in shark navigation, at least leopard shark navigation. There seems to be other cues that they are using to supplement olfactory cues.”

Nosal said the next step is determining just what other environmental cues play a role in helping sharks find their way and also better understanding just how a shark’s sense of smell works in navigation.

“There is a lot of work that still needs to be done. This is only the first step,” Nosal said. “We need to know what exactly the sharks are smelling, how the mechanism works, what other senses are involved and how all these senses are integrated to produce the end result of successful navigation.”