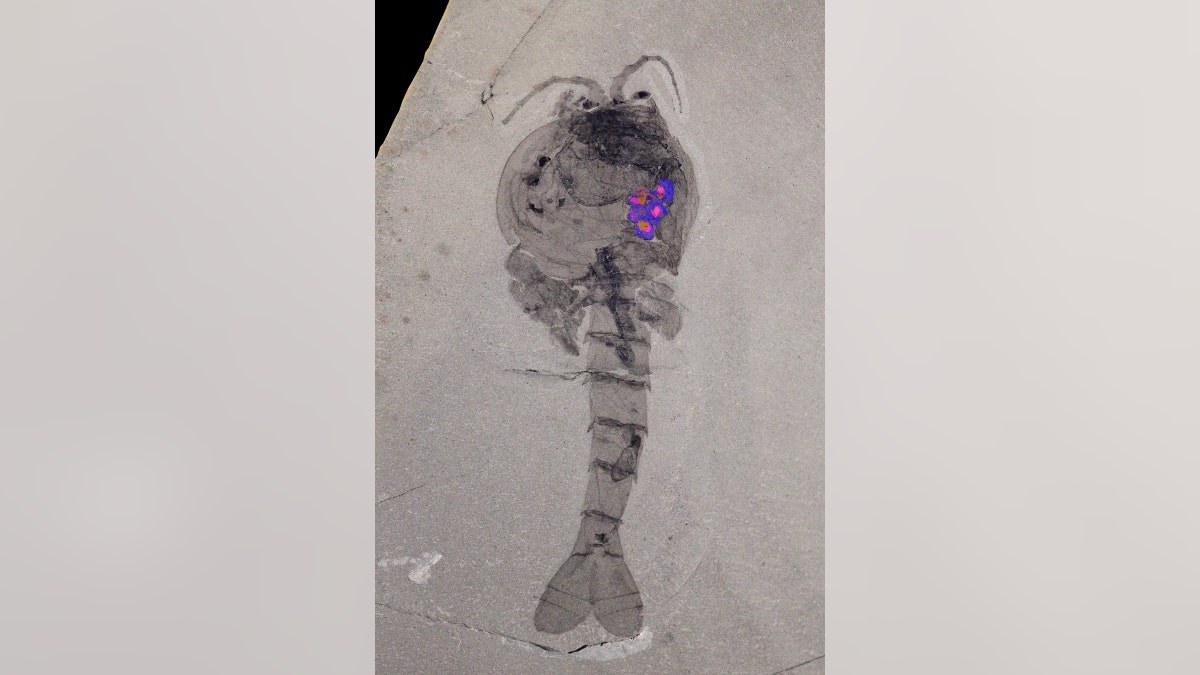

Waptia fieldensis seen with overlay of scanning electron microscope image highlighting location of eggs. (Royal Ontario Museum)

Hundreds of millions of years before kangaroos nurtured their young in a pouch, there was the Waptia.

This 508-million-year-old, shrimp-like creature, first discovered a century ago in the Canadian Burgess Shale fossil deposit, is believed to represent the oldest example of a creature caring for its young in the fossil record.

The fossil was reexamined by scientists from the Royal Ontario Museum, University of Toronto, and Centre national de la recherche scientifique and found to include uncovered eggs with embryos preserved within the body of the animal.

Related: Fossil could settle the debate over whether early birds really did fly

“As the oldest direct evidence of a creature caring for its offspring, the discovery adds another piece to our understanding of brood care practices during the Cambrian Explosion, a period of rapid evolutionary development when most major animal groups appear in the fossil record,” Jean-Bernard Caron, curator of invertebrate palaeontology at the Royal Ontario Museum and associate professor in the departments of Earth Sciences and Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto, said in a statement.

The findings first appeared in a study published this month in Current Biology.

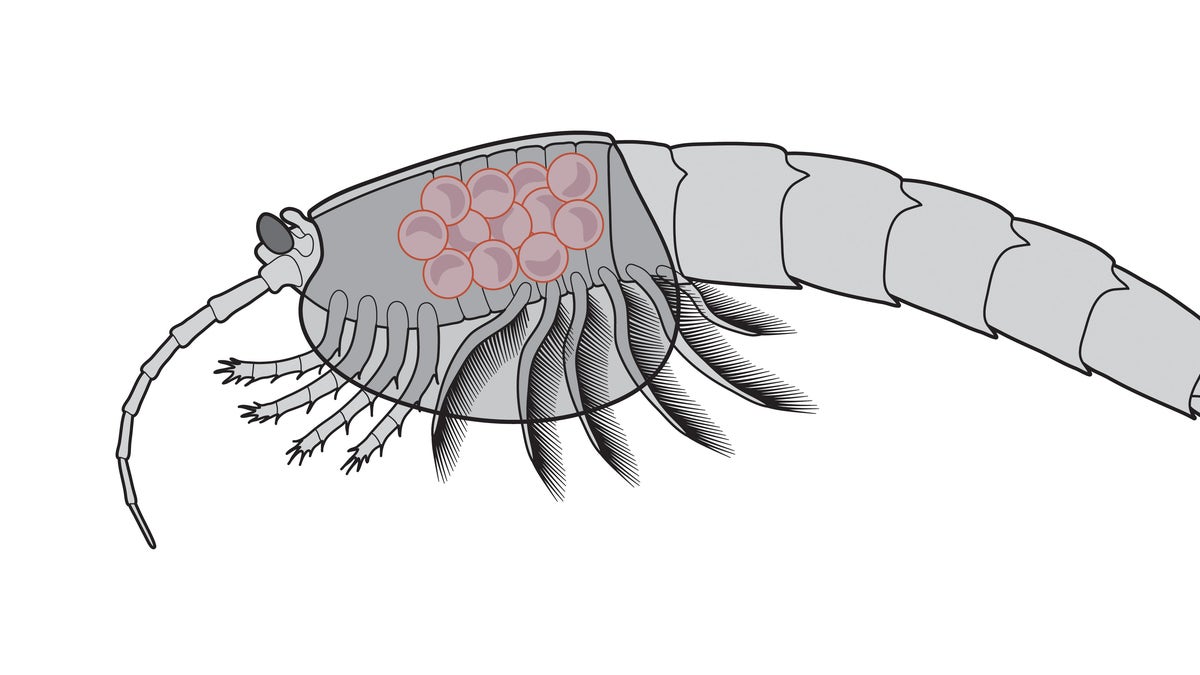

Waptia fieldensis (middle Cambrian) with eggs brooded between the inner surface of the carapace and the body. (Danielle Dufault/Royal Ontario Museum)

Related: Dinosaur egg treasure trove found in Japan

Waptia fieldensis is an early arthropod, belonging to a group of animals that includes lobsters and crayfish. It looks a lot like a crustacean, with its two-part structure covering the front segment of its body near the head, known as a bivalved carapace.

Caron and Jean Vannier, of the Centre national de la recherche scientifique, believe the carapace played a critical role in how the creature practiced brood care.

“Clusters of egg-shaped objects are evident in five of the many specimens we observed, all located on the underside of the carapace and alongside the anterior third of the body,” Caron said.

Related: Scientists tap tech to reveal dinosaur egg secrets

The clusters are grouped in a single layer on each side of the body and are clearly visible within the fossil. In some specimens, eggs are equidistant from each other, while some others are closer together, probably reflecting variations in the angle of burial and movement during burial. At most, there were 24 eggs.

“This creature is expanding our perspective on the diversification of brood care in early arthropods,” said Vannier, the co-author of the study. “The relatively large size of the eggs and the small number of them, contrasts with the high number of small eggs found previously in another bivalved arthropod known as Kunmingella douvillei.”

The researchers noted that Kunmingella douvillei’s mothering strategy predated Waptia by about 7 million years and demonstrated how different parenting methods evolved independently. Together with previously described brooded eggs in ostracods from the Upper Ordovician period 450 million years ago, the discovery also supports the theory that the presence of a bivalved carapace played a key role in the early evolution of brood care in arthropods.