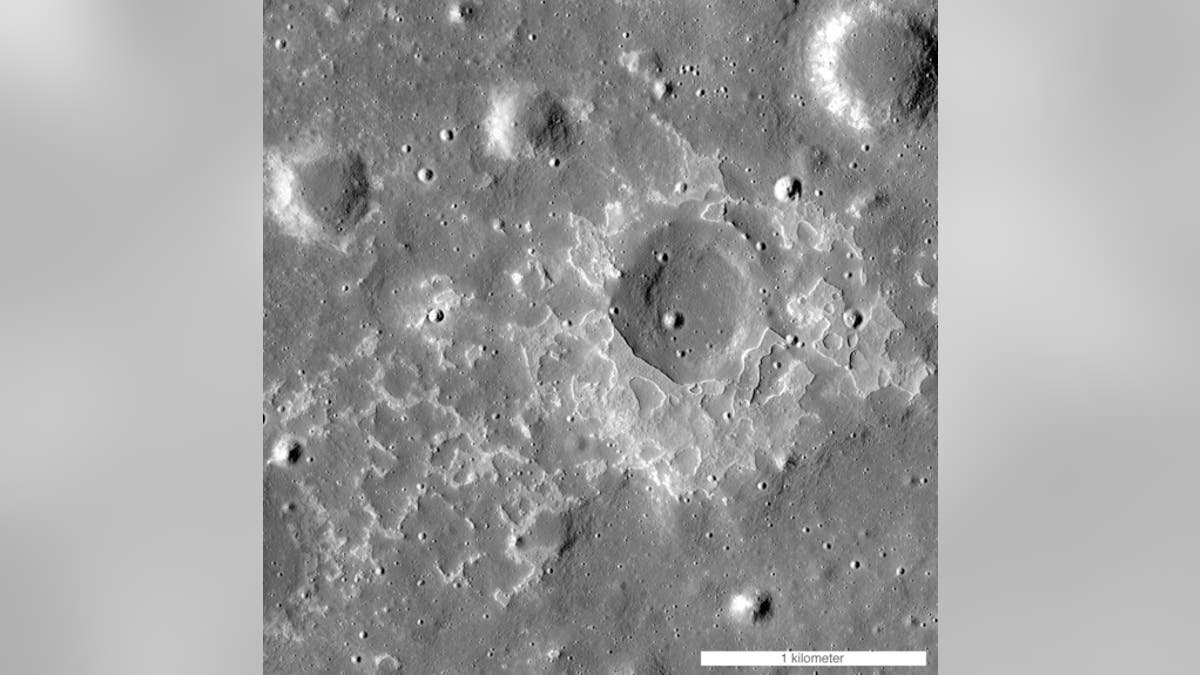

Called Maskelyne, this feature is one of many newly discovered young volcanic rock deposits on the moon. These deposits are known as irregular mare patches and they are thought to be remnants of small basaltic eruptions. (NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University)

If only dinosaurs had invented telescopes, they might have seen lava occasionally oozing from the surface of the moon.

Scientists previously thought that the moon's volcanic activity died down a billion years ago. But new data from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, or LRO, hints that lunar lava flowed much more recently, perhaps less than 100 million years ago.

"This finding is the kind of science that is literally going to make geologists rewrite the textbooks about the moon," John Keller, LRO project scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in a statement.

While in orbit around the moon, Apollo 15 astronauts took images of a strange volcanic deposit known as Ina. Research suggested that Ina was quite young and might have formed in a localized burst of volcanic activity, though most of the moon's volcanism occurred between 3.5 billion years ago and 1 billion years ago.

But now photos from the LRO spacecraft — an orbiter that arrived at the moon in 2009 — show that Ina has lots of company. Scientists spotted 70 similar patches in the dark volcanic plains on the side of the moon that faces Earth.

These distinctive rock deposits are called irregular mare patches. They're marked by a mixture of smooth, rounded mounds with blotches of rough, blocky terrain, and, on average, they're less than a third of a mile across. As such, they're typically too small to be seen from Earth.

The high number and wide distribution of these patches suggests that volcanic activity was quite widespread not so long ago (at least geologically speaking). Three of the deposits are thought to be less than 100 million years old, and Ina might even be less than 50 million years old, according to the study. The researchers said they used a technique that links crater measurements to the ages of moon dirt samples scooped up during the Apollo missions and the Soviet Union's robotic Luna missions. The findings were detailed online Oct. 12 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

The discovery of these deposits could also change the way scientists think about the temperature of the moon's interior.

"The existence and age of the irregular mare patches tell us that the lunar mantle had to remain hot enough to provide magma for the small-volume eruptions that created these unusual young features," Sarah Braden, a recent Arizona State University graduate who led the study, said in a statement.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.