Former Vice President Al Gore (AP)

Four presidential elections dating back to 1800 failed to produce a clear winner after an initial count of the votes. Regardless of the national popular vote tally, it takes a majority of the Electoral College —now 270 votes — to elect a president. Here's what happened when no candidate appeared to have a majority after Election Day:

___

1800 — The Constitution did not initially provide for separate Electoral College votes for president and vice president. Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr were running on the Democratic-Republican party ticket for president and vice president, and tied with 73 electoral votes each. The responsibility for choosing the president shifted to the House of Representatives, where each state delegation cast one vote. It took 36 ballots and much intrigue before Delaware abstained from the vote and allowed Jefferson to muster a bare majority to become president. The 12th Amendment would be ratified in time for the 1804 election, requiring electors to cast two votes — one for president and the other for vice president.

DANIEL HENNINGER: TRUMP THE OPERA

1824 — Andrew Jackson had a popular-vote plurality and the lead in electoral votes, but no majority, after the ballots were counted. Under the 12th Amendment, the House again was to make the final choice among the top three candidates — Jackson, John Quincy Adams and William Crawford, then the treasury secretary. Jackson and his supporters thought that as the leading vote-getter, the hero of the Battle of New Orleans should be elected. But House Speaker Henry Clay, who was no fan of Jackson, threw his support to Adams and ensured his election. Clay became Adams' secretary of state, drawing bitter complaints that they had struck a "corrupt bargain."

1876 — This was the second election in which the popular-vote winner, and the leader in the Electoral College, did not become president. Democrat Samuel Tilden topped Republican Rutherford Hayes and was one vote shy of an Electoral College majority. Twenty electoral votes were in dispute and not awarded to either man. The controversy, wrapped in race and Reconstruction politics, dragged on. Congress created an electoral commission made up of five senators, five representatives and five Supreme Court justices to determine the winner. The commission, though, had eight Republicans and seven Democrats, and ultimately awarded the contested votes to Hayes as part of an informal compromise that led to the withdrawal of troops from the South and the end of Reconstruction.

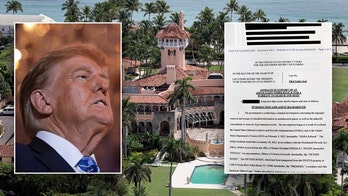

EARLY VOTING SHOWS HIGH LATINO TURNOUT

2000 — A few hundred votes separated Republican George W. Bush and Democrat Al Gore in Florida, leaving the outcome of the election in doubt. Gore won the nationwide popular vote, but needed four more electoral votes. The dispute over Florida's 25 electoral votes lasted more than a month, as a recount began and Americans learned the word "chads" — the parts of a paper ballot that voters were supposed to punch out in making their choices. The Supreme Court ultimately halted recounts ordered by Florida's top court. That decision left Bush's 537-vote margin in place, out of nearly 6 million votes cast in the state.