Supreme Court upholds 'one person, one vote' rule

Strategy Room: David Mercer and Brad Blakeman break down the ruling on how voting districts are drawn

The Supreme Court decision Monday that said states can continue to count all residents, not just eligible voters, when drawing election districts was seen as a blow to conservatives who challenged the current system -- but the debate is not going away.

While the 8-0 decision Monday was unanimous, it fell short of settling the larger issue of fair representation in the political system. The justices clearly allowed what is often referred to as the "one person, one vote" principle -- but did not order states to use it.

That means the court potentially opened the door to another challenge later on. Even Justice Samuel Alito suggested in his opinion that the court will rule on the broader representation question more definitively “when we have before us a state districting plan.”

All sides essentially agreed that the ruling is a setback, though only temporary, for conservatives who challenged the existing, all-inclusive system -- and a win for Democrats, who largely represent urban areas full of Latino and other immigrants who cannot vote.

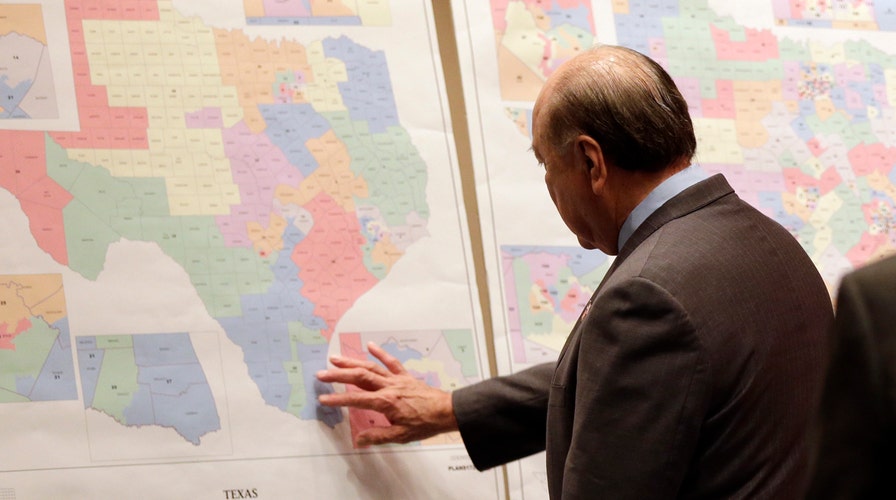

The case was presented by two Texas voters who were essentially testing a 1964 Supreme Court ruling that political districts must be roughly equal in population.

All 50 states use total population, and not eligible voters, as their basis for drawing district lines.

But in the Supreme Court case, Evenwel v. Abbott, the challengers said their rural state Senate districts in Texas had vastly more eligible voters than urban districts, making their votes count for less in violation of the Constitution.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said in summarizing her opinion for the court that elected representatives “serve all residents, not just those eligible or registered to vote" and that non-voters have an important stake in many policy debates.

However, the high court stopped short of saying that states must use total population. And it also did not rule on whether states are free to use a different measure, as Texas had asked.

Edward Blum, whose Project on Fair Representation backed the lawsuit, said he was disappointed in the outcome but predicted "the issue of voter equality in the United States is not going to go away."

Justices Alito and Clarence Thomas declined to join Ginsburg's opinion.

Thomas said the Constitution gives the states the freedom to draw political lines based on different population counts but the high court in deciding the 1964 case, Reynolds v. Sims, "never provided a sound basis for the one-person, one-vote principle."

Ilya Shapiro, a senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute, said the court avoided "the elephant in the voting booth” by not addressing whether the one-person, one-vote principle requires “equalizing people or voters when crafting representational districts.”

The Democratic National Committee on Tuesday also argued the issue is far from over and suggested it that could resurface before the completion of the 2020 census, on which redistricting maps are based.

“There are new Republican-led challenges to voting rights that have materialized,” the group said. “We are already seeing the effects of these challenges in Wisconsin, Arizona and North Carolina -- three critical battleground states in the general election.”

Alito, in his opinion, further suggested the issue will re-emerge.

“For centuries, political theorists have debated the proper role of representatives, and political scientists have studied the conduct of legislators and the interests that they actually advance,” he wrote. “We have no need to wade into these waters in this case, and I would not do so.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.