Hunt intensifies for terrorists behind Brussels strikes

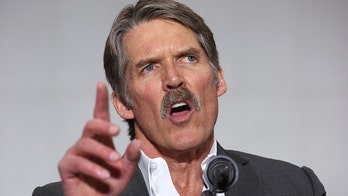

On 'Special Report,' Greg Palkot with the latest details about the attacks

Sometimes what Congress doesn’t do is more significant than what it does do.

At first blush, the virtual absence of discussion regarding Congress approving a new Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) to combat ISIL in the wake of the Brussels terrorism attacks might be breathtaking.

But let’s make something clear: Congress was never going to approve a constitutionally-mandated authorization to take on the Islamic State, regardless of whether terrorists rocked Brussels -- or hit Paris or the offices of Charlie Hebdo.

This is a debate about a debate that hasn’t happened for close to three years now.

Many lawmakers from both major political parties think Congress and the administration may potentially run afoul of the Constitution and the law when sending U.S. forces to strike and combat ISIL or ISIS, a the terror group is otherwise known, without a specific blessing from Capitol Hill.

But it might not matter as to the success or failure of defeating ISIL.

That’s because many are completely disheartened about the strategy -- or the paucity of any strategy -- whether it arises from the White House or the halls of Congress.

“The administration is not going to change its strategy,” said one senior Republican lawmaker.

And neither the House nor Senate plans to vote on any authorization anytime soon.

For years, the administration and some lawmakers of both parties asserted that Congress didn’t need to adopt a new authorization for ISIL.

Congress approved a broad, open-ended war authority just days after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The next fall, Congress sanctioned another resolution to pre-emptively invade Iraq. There is a dispute as to whether those authorizations maintain standing in the current conflict with ISIL.

As for a new AUMF? Its goose may have been cooked as far back as August, 2013.

British Prime Minister David Cameron lost a symbolic vote in the House of Commons that August that would have granted the United Kingdom authority to join the U.S. in airstrikes against the Syrian regime after the use of chemical weapons.

“The British people do not want to see British military action and I get that and the government will act accordingly,” said Cameron following the vote.

In Washington, lawmakers streamed back to the Capitol over the summer recess for intelligence briefings and to hear about the U.S. plan to get involved. The vote in London was reasonably close. But there were never more than a few handfuls of votes on Capitol Hill to back President Obama’s effort in Syria.

So Congress sat that one out -- and hasn’t truly revisited the issue since.

That’s not to say there hasn’t been talk.

More than a year ago, Obama crafted an ISIL authorization that he sent to Capitol Hill. Then-House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, sat on it for months.

Come spring of 2015, Boehner declared the authorization dead and asked for another one. The administration didn’t bother.

The issue lay dormant until November. Terrorism attacks in Paris and San Bernardino bolstered interest in an AUMF.

There was discussion over the winter at the House and Senate Republican retreat in Baltimore about designing an authorization.

House Speaker Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., commissioned listening sessions to consider “whether and how” Congress could or should forge an AUMF. Coalitions of bipartisan lawmakers indicated it was critical that Congress weigh in on the fight.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., took a plan designed by Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and set it up for possible floor debate, bypassing any committee preparation. But so far, the Senate hasn’t touched that initiative, either.

Rep. Thomas Massie, R-Ky., was one of the few who directly commented about an AUMF after Belgium on the day of the attack.

Massie struggles with the mission creep of the 2001 and 2002 authorizations. He says any new authorization should supersede the old ones and be “limited in scope, enemy and geography.”

Writing an AUMF is challenging because nobody wants to handcuff a president. But they also don’t want to green-light open-ended war.

Why no authorization after all of these years? There are a couple of reasons.

First, lawmakers are loathe to commit to war -- especially considering the Iraq and Afghanistan experiences. Those still resonate.

Secondly, members of Congress don’t think the public can stomach ground troops. Air strikes may not be enough. But is the U.S. public really ready for ISIL to release videos of them incinerating U.S. service personnel locked in cages? Is it any wonder Congress simply lacks the votes or wherewithal to touch any AUMF?

That said, the recent U.S. strike on an al Shabaab training camp that killed 150 fighters in Somalia prompted questions as to whether the military stretched existing war-making authority.

American forces have the right to defend themselves in peace and war, regardless of a congressional resolution. But it’s unclear if the self-defense doctrine applies in this case.

Still, if the U.S. doesn’t engage, there’s a possibility Europe might.

Terrorists have struck Europe three times in a little more than a year.

“Our European partners are going to leave us behind,” predicted one lawmaker who asked not to be identified. “Belgium was on the highest alert since November. The attack in Brussels was more compelling that what the intelligence showed (ISIL) was capable of.”

European action could compel Congress to act on an AUMF since terrorists have attacked two major European capitals. One wonders how that fated August, 2013, vote in the British House of Commons might go now.

But what’s strange. Congressional approval of an AUMF to counter ISIL doesn’t necessarily improve the strategy. To be clear, lawmakers on all sides believe it’s important that Congress align with the Constitution on war powers.

However, the discussion about completing an AUMF as an end to defeating ISIL may be an academic debate -- not a practical one.

An authorization does not necessarily translate to a strategy -- let alone a successful strategy.

The irony is the debate over an AUMF lingered for years and the ISIL threat only matured.

Of course, Congress was resolute in its decision to pursue al Qaeda and the Taliban after 9/11. It took an event on the scale of Paris, Paris and Brussels combined to stoke those fires on Capitol Hill.

With two existing AUMF’s from 2001 and 2002, would an attack on U.S. soil start the AUMF debate anew in Washington? Unclear.

But the real question is whether a new AUMF would make any difference.