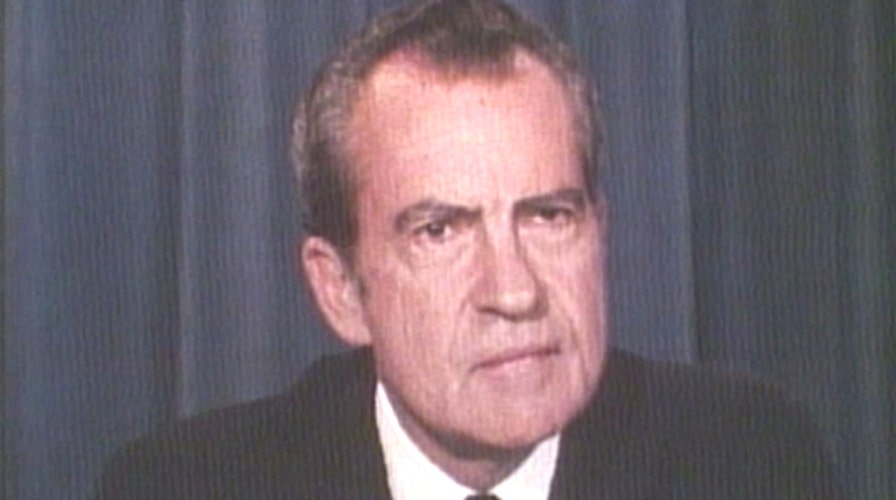

Flashback: President Nixon's resignation speech

August 8, 1974: Richard Nixon tells the nation that he will resign as the 37th president of the United States

He had seen it coming for a long time – but that didn’t make doing it any easier. As early as April 1973, 16 months before the act, President Richard Nixon mused aloud about resigning his office. Now, at last, the hour of decision was upon him.

How had it come to this? Against incredible odds and amid explosive upheavals, this brooding and solitary creature, now facing ignominy on an unparalleled scale, had been one of America’s most popular and enduring politicians: one of only two men in U.S. history – Franklin D. Roosevelt was the other – to have appeared on a national ticket five times.

Indeed, it was only after losing the presidency by a hair’s breadth to John F. Kennedy in 1960 that Nixon had gone on to win the presidency twice. His re-election, in November 1972, marked one of America’s greatest landslides and as clear a vote of confidence from the American people as any incumbent could ever hope to receive: Forty-nine states, 60.7 percent of the popular vote, 97 percent of the electoral vote.

How, indeed, had it come to this? Had everyone forgotten the bombings, the riots, the street crime, the weekly body bags from Vietnam, the chaos and craziness that had torn America asunder from1968 to 1971? Had they forgotten the opening to China, the SALT nuclear accord with the Soviets, the rescue of Israel in the Yom Kippur War? How had he, the president, allowed the fantastical cast of characters in Watergate to entrap him, Lilliputians to his Gulliver? How had everything gone so wrong?

None of that mattered anymore, really – now, on the eighth of August, 1974, what mattered was simply that he had to do it: He had to resign, to become the first U.S. president ever to abdicate the office before his term was over. For the business of resignation, there was no road map: no historical precedent for Nixon to model, no pinstriped Wise Men with experience in this realm to consult, no former presidents alive to counsel the man soon to become America’s first and only ex-president.

Even Jacqueline Kennedy, in her hours of shock and horror and grief, had had the hundred-year-old example of the Lincoln assassination to study for some clues as to how, properly, the nation should bury its slain president. Yes, Nixon had largely brought himself to this ugly place; but given that he still needed to discharge this presidential duty the right way, needed as president to keep the country on an even keel, and protect it, in its lethal Cold War struggle with the Soviet Union, to where could he turn for wisdom?

As the president’s secret tapes were precisely the body of evidence that he had failed to destroy and was now destroying him, driving him from office under a welter of court rulings and sensational news coverage, the taping system was no longer in place to capture how Nixon went about discharging this unprecedented exercise of presidential power. The system had been dismantled in July 1973, when Alexander Butterfield, the White House aide who had presided over its operation and maintenance, had disclosed it to the Senate Watergate committee. The Nixon tapes made the Nixon administration the best-documented regime in the history of mankind. Never again are we likely to see so comprehensive a real-time record of the nuclear-age presidency – 3,700 hours of voice-activated recordings from the Oval Office, the Executive Office Building, Camp David, various telephone lines – generated or preserved.

But the absence of the tapes for the final year of the Nixon presidency is acutely felt by history. A lack of evidentiary clarity haunts our understanding of the latter stages of Watergate: the Saturday Night Massacre; the full extent of the collusion between the Watergate special prosecutors and Judge John Sirica (amply documented by Geoff Shepard in The Atlantic); the intrigues of chief of staff Alexander Haig; the private conversations between Nixon and his successor, Gerald R. Ford, and the unfathomable depths of the presidential pardon Ford issued his predecessor, in September 1974. Oral histories, diaries, memoirs, and memoranda fill some of the void, but there is much we will never know.

We know that the women in Nixon’s life – his beautiful wife, Pat and their two lovely daughters, Julie and Tricia – wept and pleaded with him to fight the impeachment trial that lay ahead. Not swayed, Nixon worked with his speechwriter, Ray Price, to craft a resignation speech somehow equal to the magnitude of the moment. Presidents and their speechwriters had written a lot of speeches in 200 years, but never one like this.

Among the most urgent considerations: An acknowledgment of epic presidential failure was obviously necessary, but it also had, with equal necessity, to be balanced against the perils of an ongoing criminal inquiry against Nixon and his top aides, led by the most partisan Kennedy supporters and with no boundary or termination point in sight; hell, even Nixon’s back taxes were under investigation!

Two hours before the president opened the primetime Oval Office address to the nation he had scheduled, some White House aides whispered to reporters that they still didn’t think the Old Man would quit. “I’ll believe it when I see it,” they said. A reporter stationed in San Francisco that night reported that most citizens of California were paying scant attention to the epochal events occurring back East. For them it was “as if almost it’s all happening in some other country to some other people.”

When he began, the 37th American president bade his viewers and listeners a good evening and noted that this was the 37th time he had addressed them from the Oval Office. That there was something foreordained, a sense of grim fate, about the Nixon presidency was not lost on the man who embodied it. Nixon spoke of the erosion of his political base in Congress, without which he saw no point in fighting the Watergate impeachment drive to its conclusion. “The interests of the Nation,” he said, “must always come before any personal considerations.”

I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body. But as President, I must put the interests of America first. America needs a full-time President and a full-time Congress, particularly at this time with problems we face at home and abroad.

To continue to fight through the months ahead for my personal vindication would almost totally absorb the time and attention of both the President and the Congress in a period when our entire focus should be on the great issues of peace abroad and prosperity without inflation at home.

Therefore, I shall resign the Presidency effective at noon tomorrow. Vice President Ford will be sworn in as President at that hour in this office.

The speech was received well. In their instant analysis – the advent of which, in his first term, had driven Nixon bonkers: Who the hell were Walter Cronkite and Dan Rather to tell the American people what to think thirty seconds after the president had just finished addressing them on Vietnam? – the team at CBS News generally spoke approvingly. “It seemed to me as effective, magnanimous, a speech as Mr. Nixon has ever made,” said commentator Eric Sevareid, “and I suppose there’d be many, even among his critics, who will say that perhaps few things in his presidency became him as much as his manner of leaving the presidency. Certainly, no attacks on his enemies, none on the press. ... I think people will find it very hard to find fault with this.”

Rather, perhaps Nixon’s most spirited antagonist in the White House press corps, emphasized the rule of law in America, and said Nixon’s address “made clear that he respects that. He understands that. He has that appreciation and that awe for it. ... He gave to this moment a touch of class; more than that, a touch of majesty, touching that nerve in most people that says to their brain: We revere the presidency, we respect the president; the Republic and the country comes first.”

In Nixon’s own mind, however, the formal address was only half the story, half of what he needed to say, half of what the country needed to see and hear at this agonizing moment. The following day, before boarding the helicopter that would take him to Andrews Air Force Base for the long ride home to California, he would say a few words in farewell to the White House staff in the East Room.

Where the previous evening had seen him formal and composed, here Nixon was loose and emotional: speaking of his mother as “a saint,” his father as a failed lemon rancher, the “great heart” of the White House itself. He wore his glasses in public for the first time, came near to weeping: allowed a sense of vulnerability to enter his public persona. Flanked by his daughters and their husbands and his long-suffering, loyal Pat – whom he failed to acknowledge: the only major flaw in his execution – the president spoke philosophically of taking knocks, valleys and peaks. He even joked about his back taxes problem.

All this, too, the Republic needed to see and hear at this fragile time: that Richard Nixon was human, for God’s sake; or, as Neil Young would put it in “Campaigner” (1976), “Even Richard Nixon has got soul.” In fact, what Americans most required of the president, and what he most desperately needed for himself, was some sign of transcendence in the man: some demonstration that he had managed, if only for his final day in office, to surmount the vengefulness and smallness of spirit that had too often afflicted him in the White House. We needed to know that even after this most shattering national tragedy, there could yet be “a new Nixon,” that the prospects for grace, amazing or even mid-sized, were not altogether extinguished in stagflated 1970s America.

And this, too, in the penultimate paragraph of his maudlin East Room soliloquy, Nixon delivered. The final accomplishment of the Nixon presidency came when this supremely disgraced and vilified figure showed the American people a measure of personal transcendence; and it is to Nixon’s eternal credit that the chief executive embedded the true lesson of Watergate not in some final stab at exculpation but in an exhortation for young people, the era’s most disillusioned characters, to serve in government.

“Always give your best, never get discouraged, never be petty,” Nixon said. “Always remember: Others may hate you, but those who hate you don't win unless you hate them – and then you destroy yourself.”

________________________

James Rosen is chief Washington correspondent and author of The Strong Man: John Mitchell and the Secrets of Watergate.