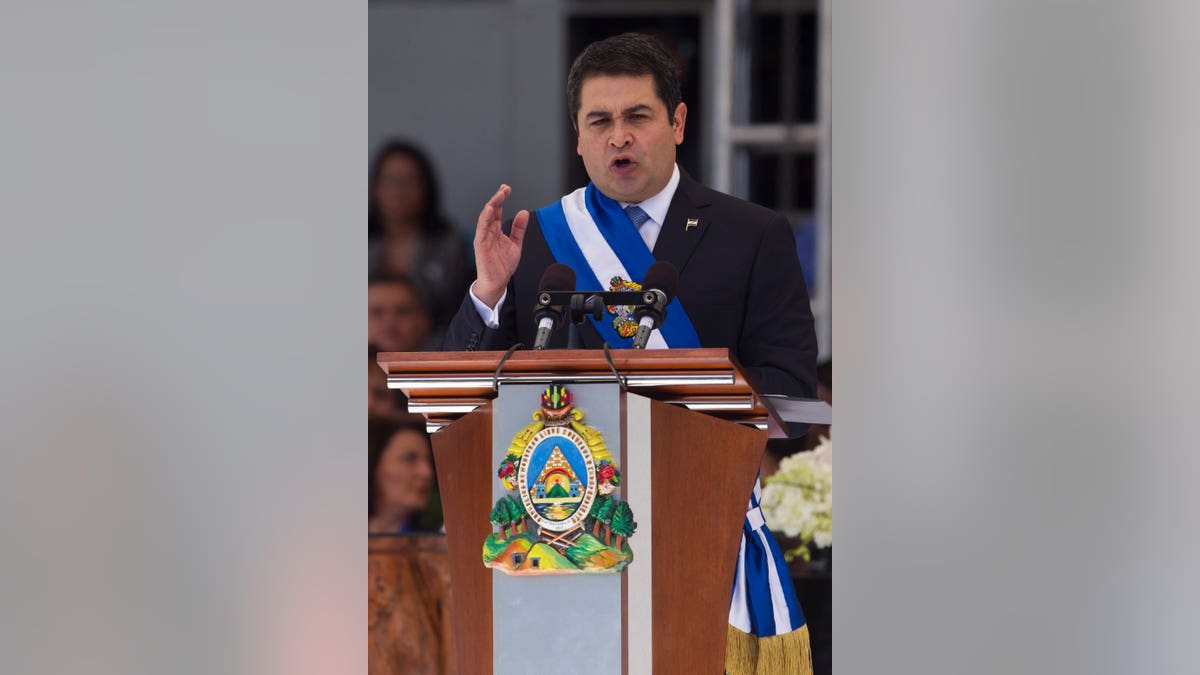

Honduras' President Juan Orlando Hernandez after his swearing in on Monday, Jan. 27, 2014. (ap)

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, on a visit to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce on Friday, said the U.S. has to strengthen efforts to control the humanitarian crisis that both nations face with unaccompanied migrant children crossing the U.S. Southwest border.

At the end of his speech to the chamber, where the Honduran head of state discussed his nation’s short- and long-term investment projects with U.S. businesses, Hernández seemed to blame the U.S. for the crisis – saying a lack of immigration reform and weak drug laws has contributed to the problem.

It is unfair, he said, for his nation to tackle the surge of migrant unaccompanied children alone.

“We are very worried about the children, but sadly this is a security problem provoked by drug trafficking from the drugs that are consumed by the US, and this has had an impact in the displacement situation (of Hondurans,)” Hernández, who took office in January, told Fox News Latino. “The U.S. has to be more proactive (with the immigration reform) because these separations are inhumane.”

To tackle the humanitarian crisis of the migrant unaccompanied children, Hernández said his government has asked Mexican officials to immediately set up four new Honduran consulates in the Mexican-Honduran border known as “Ruta del inmigrante” to provide humanitarian aid and custom and immigration support as the flow of people – mostly children alone or with their parents – reach the area.

An estimated 60,000 children are expected to reach the U.S. this year. Officials in Washington have called it a humanitarian crisis and several shelters have been opened throughout the country to care for the children — but authorities have made it clear that those who enter the country illegally, regardless of their age, will be returned to their countries of origin.

Three out of four unaccompanied children arrested this year are from Central America.

Most of them are from Honduras, which has seen the biggest increase in unaccompanied minors coming to the United States.

According to Pew Research Center, more than 13,000 kids arrested at the border so far this year are from Honduras; five years ago the number was less than 1,000. And this year, the number of children coming alone from Honduras already is about twice as high as it was for all of 2013.

Those coming from Guatemala this year have numbered 11,500, and from El Salvador, nearly 1,000.

The Honduran president asked Congress to boost its financial aid to his nation for social programs. Hernández also said he wants the U.S. to work jointly with Honduras to fight drug cartels as they have done in the past with countries such as Colombia and México.

In 2014, the Department of State announced it would slash $285 million in aid to Latin America to fight drug cartels and to finance military training and social programs.

President Hernández insisted his nation is confronting drug cartels directly, and extraditing cartel members, and making an investment in security issues in his nation like never before. But, he said, he feels the U.S. is not taking the same kind of action.

“Sadly, here some U.S. officials think this problem is a health one, not a life and death situation like it is for us,” he said. “And it’s not fair that if we are a (drug) transit country, we deal with this (issue) alone. This is a problem that we didn’t create but originates with drug consumption here (in the U.S.).”

In a recent interview with Fox News Latino, Marc Rosenblum, deputy director of U.S. Immigration Policy Program, a Washington-D.C.-based think tank, said no one can predict how long this surge of unaccompanied migrant children is going to last, and how many people it will ultimately affect.

Rosenblum said one of the big challenges for the U.S. is to strike a balance between responding to the crisis in a humane way without encouraging more immigrants to cross the border.

Some experts say that the homelands of the children who are fleeing to the United States must take some responsibility for the border crisis.

“That the U.S. shares some responsibility there's no doubt,” said Christopher Sabatini, a senior director at the Council of the Americas, said to Fox News Latino. “But responsibility for this has to be shared, in terms of ensuring the human treatment of immigrants and migrating children, border security and addressing the scourge of corruption.”

“Yes, the U.S. Congress must address immigration reform,” he said. “But that will not put an end to the problems of transit and security south of the border. The U.S. simply cannot do all of that on its own no more than it can [stop] the consumption of drugs tomorrow or [reduce] the incentives for immigrants to come to the U.S. to seek a better life.”