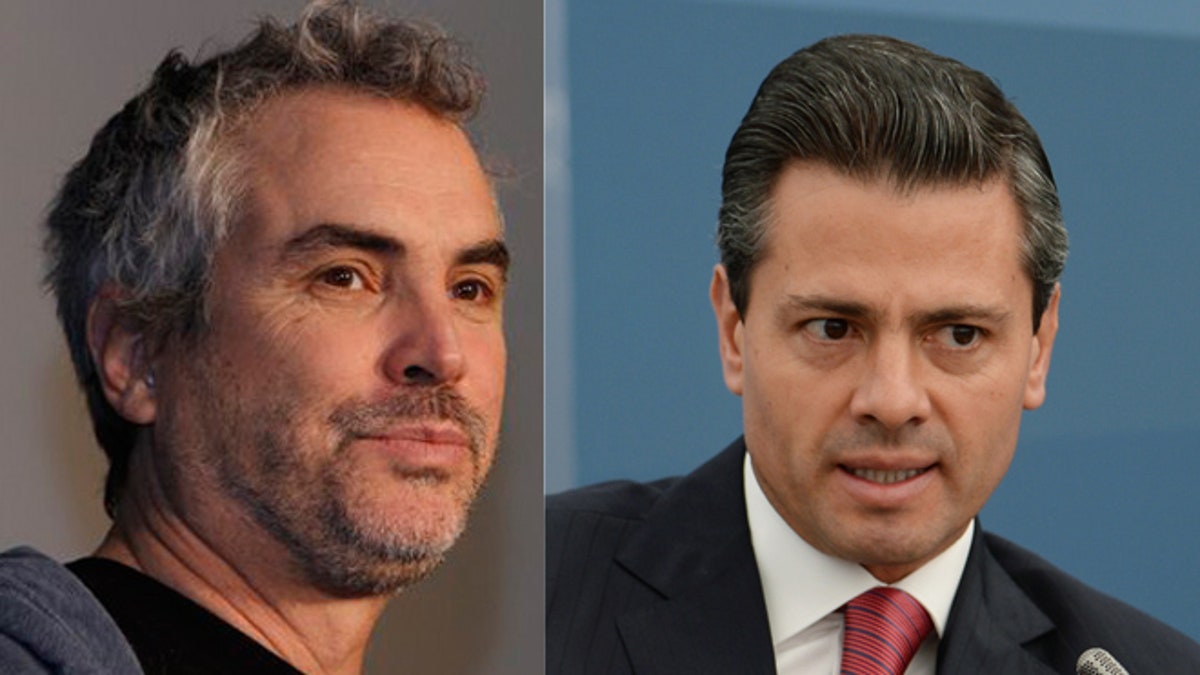

MEXICO City – Mexican celebrities seldom call out politicians or offer opinions on public policy. But Oscar-winning film director Alfonso Cuarón leveraged his star status by issuing an open letter on Tuesday, posing 10 questions for President Enrique Peña Nieto on government plans to overhaul the state-run oil industry.

He also alleged in his letter that the process for approving the reforms left Mexicans in the dark on “the deepest and most transcendent [issue] Mexico has had in decades,” and which the director said, “changed the paradigm of national development.”

Peña Nieto first thanked Cuarón via Twitter for “enriching the debate.”

On Wednesday, two of his ministers read responses to a pair of questions moments after they introduced legislation required for regulating the industry, which will be open to foreign investment for the first time in more than 80 years.

The president's office later published detailed responses – in a 13-page PDF document via a website promoting energy reform – which promised lower prices for propane and electricity, the production of an additional 500,000 barrels of oil per day within four years and 2 percent greater economic growth annually by 2025.

The incident showed the strength of Cuarón’s star status in his home country, where he hasn’t always been on the best terms with the film establishment. But it also broke from the standard celebrity culture of stars largely staying on the sidelines during big debates.

“Even though there are personalities in Mexico who shine inside and outside of the country, very few dare to start trying to influence public opinion,” Aldo Muñoz Armenta, political science professor at the Autonomous University of Mexico, told Fox News Latino.

“It’s a tragedy, but in Mexico there are few places to shine. What allows you shine most is politics or businesses associated with politics,” he said.

Mexican celebrities often appear in the society pages in the company of politicians. Some even sell their services to political projects and parties – such as the soap opera stars who appeared in 2009 ads for the Green Party, calling for a return of the death penalty.

Some Mexican states hire celebrities as spokespersons or representatives – such as Nuevo León, which contracted actor Gael García Bernal for a tourism campaign – in part because of prohibitions on politicians appearing in such ads.

The close ties between celebrities and politicians dates back decades and is attributed by some to the tightness between the federal government and broadcaster Televisa – whose founder considered the company a “soldier” of Mexico's ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which for decades held an iron grip on the Mexican presidency, but was voted out of power in 2000.

“For decades, any actor or singer who criticized the president or the ruling party risked being blacklisted by Televisa,” says Andrew Paxman, co-author of the Spanish-language book, ‘El Tigre: Emilio Azcárraga and His Empire, Televisa.’

“Azcárraga said in 1997 that the company was no longer a ‘soldier of the PRI,’" Paxman told FNL, "and implied that employees could speak their minds, but it hasn't happened much.”

Peña Nieto, who took office in December 2012, is the first PRI president since 2000.

Cuarón – director of such movies as "Y Tu Mamá También" and "Gravity" – lives in London. For much of his career, he has been on the outs with the entertainment establishment in his home country, much of which depends on government grants and a private sector concerned about having the proper political connections.

Cuarón's criticism of the oil industry overhaul comes as many in the country express skepticism at a package of reforms advanced by Peña Nieto in areas such as competition, telecommunications and taxes – measures lauded by international investors and which the president says will allow the country to grow by more than 5 percent annually.

Polls show Peña Nieto having an approval rating of less than 50 percent, in part due to the economic slump and new taxes that have diminished consumption in the first few months of 2014.

Mexico expropriated the petroleum industry in 1938 and many consider the national ownership of it a symbol of sovereignty and prestige – even after production has declined and the state-run oil agency Pemex has been beset with issues of corruption and an inability to take on technologically difficult projects such as deep-water drilling.

Peña Nieto’s plan, which sailed through the Mexican Congress, calls for allowing outside companies to compete for contracts in Mexico, while all reserves would remain state property until actually exploited. Private players could also participate in operating pipelines, refining and generating electricity.

Pemex’s profits provide one-third of revenue for the Mexican federal budget, but the agency has traditionally been short on funds for exploration – something the federal government says will change with energy reform as Pemex is treated more as a normal company, not a government cash-cow.

Still Cuarón alleged in his letter that the plan isn’t especially well understood by the public, pointing to the quickness with which the reform was approved in Congress and by various state legislatures – with one approving the measure after less than 10 minutes of deliberation.

“My lack of information is not attributable to ‘groups in opposition’ that have ‘generated misinformation,’” Cuarón said in his letter.

“The reason is more simple: the democratic and legislative process of these reforms was poor and lacked a deep discussion, and the diffusion of its contents was given in the context of a propaganda campaign that avoided public debate.”

Veteran Pemex observer George Baker agreed that debate has been lacking on energy reform in Mexico, observing that Peña Nieto’s own party obstructed attempts at overhauling the industry until it won back power in 2012. But he says that the Cuarón letter did little to advance the debate.

“This is the language of what? The language of Ross Perot,” he commented.

Cuarón urged Mexicans on Thursday to follow the energy reform issue. Although he isn’t likely to lead any sort of protest movement, that doesn't mean that others couldn't be inspired by his acts.

“It suddenly makes it sound respectable or decent … to be at least skeptical about the president’s energy policies,” Federico Estévez, political science professor at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico, told FNL.

“It’s made the left’s position on this at least acceptable or respectable again; it needs to be taken into account.”

Follow us on twitter.com/foxnewslatino

Like us at facebook.com/foxnewslatino