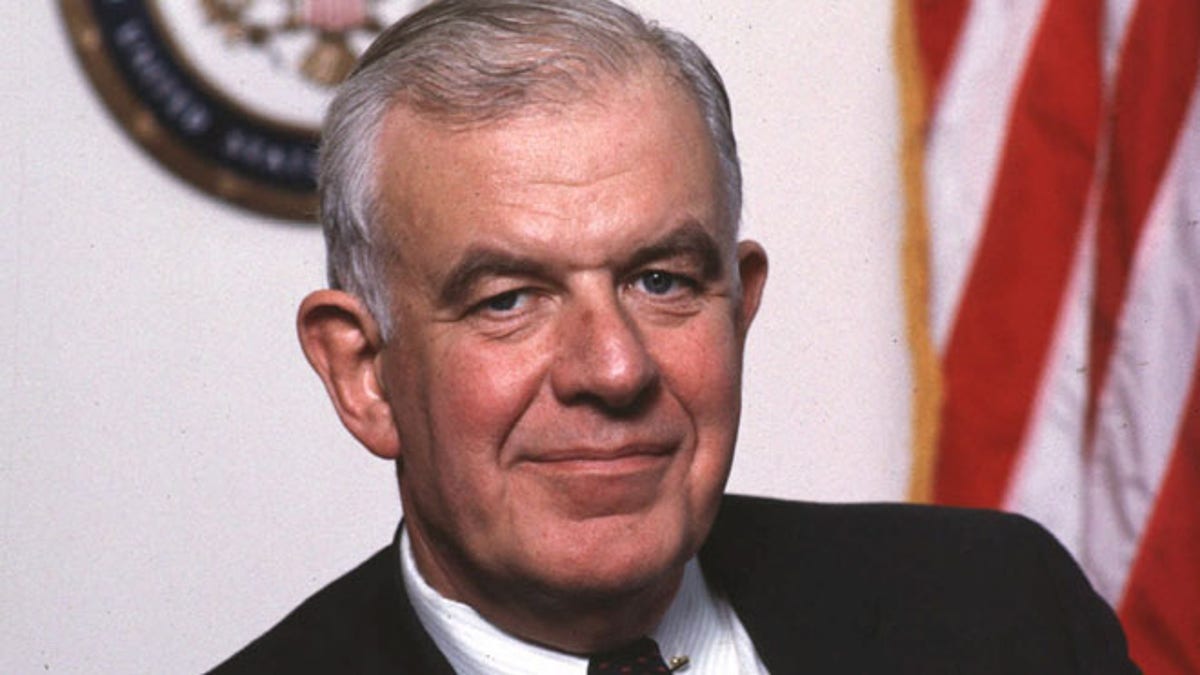

In this June 1989 file photo, former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives Tom Foley poses in his 5th Congressional District office in Spokane, Wash. (AP)

Thomas S. Foley, a Democratic speaker of the House known for his conciliatory leadership style throughout his three decades in Congress from 1965 to 1995, is dead at the age of 84.

The eastern Washington Democrat was first elected to the House of Representatives in 1964 with his party's historic gains under President Lyndon Johnson, unseating a ten-term Republican incumbent, Walter Horan, by a seven-point margin. But thirty years later, Foley was swept out of office - the first Speaker since 1860 to lose reelection - with the Republican Party's insurgence during the 1994 midterm elections.

Respected by members of both parties for his efforts at fairness and consensus, Foley's speakership was a turn from the iron-fisted ways of his predecessors Jim Wright, D-Texas, Thomas "Tip" O'Neill, D-Mass., and Sam Rayburn, D-Texas.

"There is a degree to which you can sort of push, encourage, support, direct," Foley said. "But the speakership isn't a dictatorship."

On many occasions, however, Foley's preference for compromise over confrontation frustrated his Democratic counterparts who wished that he would extract more concessions from the other party.

"Tom Foley can argue three sides of every issue," O'Neill, who first appointed Foley to the Democratic leadership, once complained.

Foley rose through the leadership ranks first as chairman of the House Agriculture Committee in 1975, then as majority whip in 1981 and majority leader in 1987. Finally, after the resignation of then-Speaker Jim Wright, D-Texas, amid an ethics scandal in 1989, Foley was elected to the speakership unopposed by his Democratic colleagues.

After the bitter partisanship resulting from the 1989 ethics scandals forcing the resignations of Wright and Tony Coelho, D-Calif., the majority whip, members of both parties hoped that Foley's speakership would usher in a new era of civility. In his inaugural speech, Foley promised "a spirit of cooperation and increased consultation."

While Foley was widely respected on Capitol Hill for his open-mindedness, at the same time, many observers thought it made him a weak leader. Foley believed that his efforts at bipartisanship were in the interest of better public policy, but he acknowledged that his negotiating style sometimes inadvertently made his party lose the upper hand.

"I think I am a little cursed with seeing the other point of view and trying to understand it," Foley said.

Under nearly four decades of Democratic dominance, Republicans had become accustomed to being shunned in the majoritarian-run House. But both parties were shocked and confused one summer day in 1989 when, during a voice vote in the chamber intended simply to showcase the Republican opposition to a bill, Foley ruled in favor of allowing them an actual recorded vote on the measure.

"[T]he Democrats just sat there because they didn't know what to do. I don't think they knew to ask for a recorded vote because they never had to," then-Rep. Mickey Edwards, R-Okla., chairman of the Republican Policy Committee, told the New York Times. "And at that point, every Republican on the floor rose spontaneously and gave Tom Foley a standing ovation."

Initially following the career path of his father, a longtime federal judge, Foley served as a deputy prosecutor for Spokane County and later as the state's assistant attorney general. His introduction to Capitol Hill came while serving as a special counsel to the Senate Committee of Interior and Insular Affairs. The then-chairman of the committee, Sen. Henry Jackson, D-Wash., encouraged Foley to run for Congress. But true to what Foley called his "Type-B"-personality, he spent a long time ruminating over his decision, ultimately filing the papers to run only minutes before the deadline.

Although Foley's constituents sent him back to Washington after 15 general elections, as time went on it became increasingly difficult to hold on to his congressional seat. The 1992 elections were the first sign of trouble for Foley: he won only 55 percent of the vote, down from 69 percent two years earlier. But his leadership position, which had long been considered an advantage for sending him back to Congress, ultimately led to his downfall in the Republican onslaught of 1994.

Meanwhile, the Washington state legislature had grappled with a measure that would have enacted term limits for state and congressional representatives to six years in office. Naturally, after spending decades in Congress, Foley was strongly opposed. He considered his record as an experienced legislator as advantageous, compared to his Republican challenger, George Nethercutt, who had no political experience.

But Nethercutt insisted that extended terms contributed to the structural problems of the federal government.

"Three terms is long enough," Nethercutt wrote in a campaign brochure. "If you serve longer than that, you'll become part of the problem."

(Ironically, Nethercutt ultimately reneged on his signature campaign promise six years later in announcing plans to run for reelection a fourth time. Despite infuriating supporters of term limits, he remained in Congress until 2005.)

But Foley's argument that his seniority helped the district stood no chance against the overwhelming anti-Washington sentiment among voters nationwide. The speaker revered the institution of Congress while voters reviled it. Being a Washington insider was no longer something the public considered worthwhile.

Further, Foley was considered more of a national figure than a local representative - and there was little he could do to circumvent the political tides of the historic wave election. Representing a moderate district proved challenging for the Speaker, who had to balance the desires of his constituents with the party's national platform.

Foley was reluctant to air negative campaign advertisements critical of Nethercutt even as the political climate encouraged pointed and personal attacks. Despite the defeat, the margin was fairly close: he lost by less than 4,000 votes out of the more than 200,000 cast.

"I've had a very long and satisfying political career," he said. "I am not in any sense bitter. I lost one election in my life; unfortunately, it was the last one."

The defeat of a sitting speaker of the House for the first time in 134 years symbolized the depth of the Republican tsunami. The Republican wave also ushered in a significant change of leadership styles, as Foley's successor, Newt Gingrich, R-Ga., made his political career by embracing confrontation.

In addition to having a reputation for fair-mindedness, Foley was later known in his career as an exercise fanatic. But he wasn't always a regular at the elite University Club gym. Despite being nicknamed "Slim" in high school for his slender physique, by 1989 Foley had accumulated 91 pounds as a result of the endless stream of Washington fundraisers and receptions.

Foley's motivation came as a result of a video tribute at a 1989 banquet held in his honor. He watched in horror as the film inadvertently documented his startling weight gain over the course of his 25 years in Congress. Quickly embracing a diet and intense workout routine (usually hitting the gym four or five times a week), he lost 80 pounds in nine months and kept most of it off years later.

Despite his high-profile defeat, one of Foley's final acts as Speaker - and as a lawmaker - was in the spirit of fairness. Like the moment in 1989 when Foley allowed the Republicans a recorded vote on a bill, he gave them another chance to feel like they were in the majority. Only this time, they actually would be a month later.

It was during the lame-duck session of 1994, a month after the Republican Party had retaken the House for the first time in four decades with 52 new seats. While the GOP was measuring the curtains for its new majority, one key member of the conference would not be returning: Bob Michel, the House Republican leader, was retiring after 38 years in Congress - all of them spent in the minority. Consequently, Michel never had the opportunity to preside over the House. Although Foley would soon be handing the gavel over to a new era of Republican dominance, he allowed Michel to preside over a session.

After leaving Congress, Foley returned to public life only a few years later when President Bill Clinton appointed him as the ambassador to Japan in 1997. In addition to the frequent international travel from his time in Congress, Foley had served on the Council on Foreign Relations, the Trilateral Commission, and as a member of the American-Japan Society, the U.S. China Council, the American Council for Germany, and the Foreign Affairs Council of Washington. He served as ambassador until 2001.