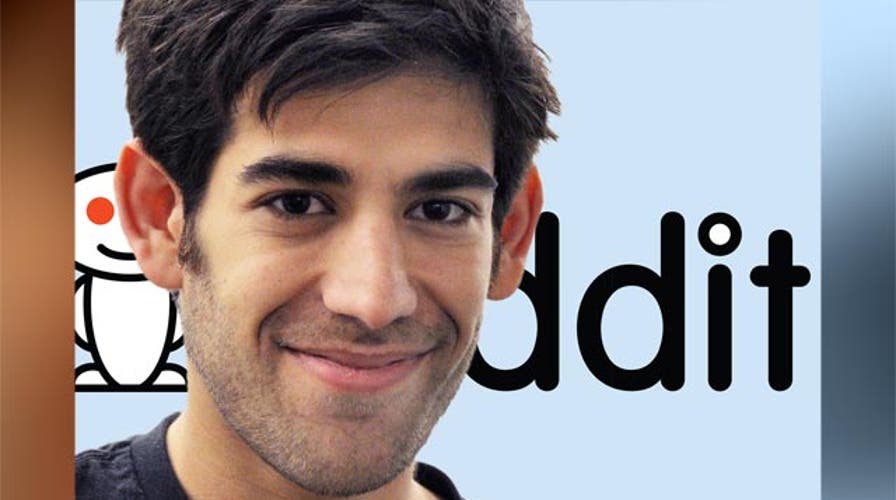

The case of computer whiz Aaron Swartz -- who committed suicide after federal prosecutors charged him with 13 felony fraud counts -- has become, for some, emblematic of how overzealous prosecutors are going too far in pursuit of a win.

The shocking suicide -- the 26-year-old co-creator of RSS and Reddit hanged himself last month -- has led to calls to rein in the practice of overcharging defendants.

Swartz could have been punished with up to 35 years in prison and $1 million in fines -- a greater penalty than some murderers face. And it was all for downloading millions of academic documents that were available at the M.I.T. Library for a small fee.

U.S. Attorney Carmen M. Ortiz issued a statement after Swartz's suicide that read in part, "At no time did this office ever seek -- or ever tell Mr. Swartz's attorneys that it intended to seek -- maximum penalties under the law."

Still, some scholars believe the Swartz prosecution is symptomatic of a fundamental shift in tactics at U.S. attorneys' offices across the country, as well as for local prosecutors.

"It has become routine for prosecutors to pile on every conceivable charge you could possibly stretch the law somehow to interpret as applicable to the conduct they're going after," said the Cato Institute's Julian Sanchez. "The reason is, of course, that it's expensive and time consuming to actually have to go to the trouble of having a trial."

University of Tennessee law professor Glenn Reynolds believes there are other motivations, too. "I think a lot of it is prosecutors chasing the numbers. I think that's one way they are measured and evaluated, so pressuring people into a plea bargain that counts as conviction makes the numbers look good," Reynolds said.

In fact, in 2010, the last year for which the data is available, only slightly more than 3 percent of criminal cases in U.S. District Courts went to trial -- a precipitous drop from earlier years which appears to back up Reynolds' concerns.

Former U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia, Roscoe Howard, tamps down the suggestion that prosecutors have adopted a win-at-all costs mentality. He says through a process called "pocket immunity," prosecutors often negotiate with defendants without coercive tactics.

"You give them limited immunity -- you tell them, 'Talk to me ... we won't use your statements against you, not the statements you give me in a meeting'. And what I'll have the chance to do as a prosecutor, is then hear what you have to say, explore it, investigate it and then decide whether I'm right."

Howard admits, though, that young and inexperienced assistant U.S. attorneys can be overzealous.

"The U.S. attorney has an absolute right not only to rein in, but they can stop assistant U.S. attorneys from doing something," Howard said. He also admits the pressure to win, especially for those seeking higher office, is great. "You know, people don't get to Congress usually by saying they're soft on crime."

Reynolds believes the practice of overcharging reflects a cultural shift away from sound legal ethics of the past.

"If you charged somebody with 50 crimes on what looked like a fairly simple thing, judges thought you were reaching and they would throw it out. Politically it looked bad -- but the culture has devolved to the point where that's just normal now," Reynolds said.

He believes the time may be ripe for a "loser pays" system in criminal trials. If a defendant is acquitted of charges, or charges are thrown out, the prosecution should bear the court costs of those charges.

"Prosecutors have absolute immunity from civil suit, so when they misbehave, when they engage in misconduct, there's no remedy for a defendant," he said.