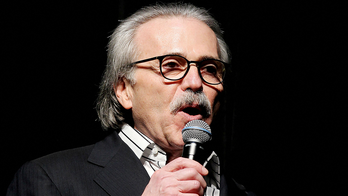

Nov. 13, 2012: AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka speaks to reporters outside the White House in Washington. (AP)

For Richard Trumka, president of the AFL-CIO, one of America's largest unions, 2012 was supposed to be a year of celebration. "What's new," he declared at a "Workers Stand for America" event, held in Washington on July 12, "is the energy we plan to put behind insisting that the power structure in America pay attention to the needs to the men and women whose labor drives this country."

And on Election Night, Trumka indeed appeared like a man with much to celebrate: Big labor's favored candidate, President Obama, had won re-election by a decisive margin, an outcome that presaged continued political benefits for labor's rank-and-file, with their time-tested ally in the White House.

But beneath the surface, things were not so sanguine. Figures released by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics last week showed that union membership in 2012 declined by 400,000 people -- a contraction of nearly 3 percent, and the fifth consecutive year the ranks of the rank-and-file have shrunk. Overall, union membership in America stands at 11.3 percent, the lowest level since World War II.

In a statement, Trumka greeted the news as a "sad truth" that augured bad tidings for the nation as a whole. "Our still-struggling economy, weak laws and political as well as ideological assaults have taken a toll on union membership," he said, "and in the process have also imperiled economic security and good, middle class jobs."

More than half of the 400,000 people who left the rolls were members of public-sector unions -- formerly a bright spot for organized labor. In addition to the factors Trumka mentioned, historians of the labor movement cited still another: the expiration of one of the signature initiatives of Obama's first term.

"I think (the decline in public-sector union membership) is directly correlated to the job loss that we've seen in the public sector, in part the result of the reduction of stimulus money, which had previously made it possible for school districts, police departments and state government offices to remain at full force," said Bob Bruno, a professor at the University of Illinois and director of its School of Labor and Employment Relations. "And as we know, a high percentage of public-sector employees are women. So to a large extent, this reduction is a product of women losing their jobs."

A significant number of those women affected, Bruno said, were public school teachers.

Long-term trends are also indisputably at work, among them America's hemorrhaging of manufacturing jobs since the early 1970s and the growth, over the same period, of immigrant populations in the U.S. However, the implications of labor's difficulties for the economy as a whole tend to depend on one's political and economic philosophy.

"With the decline of the unions has come the decline of the middle class, and this has made it very difficult for our economy to recover," Catherine Heldman, an associate professor at Occidental College, told Fox News' "Your World" on Jan. 24.

Conservatives, who see unions as largely a drag on the free market, won a round last week, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ruled that Obama's pro-labor recess appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) were unconstitutional. The ruling has thrown into doubt the legal validity of more than 200 NLRB rulings issued over the last year.

While he regards unions as indispensable to the country's economic progress over the last century, historian Eric Arnesen, a professor at George Washington University, cited the unions themselves for contributing to their own problems.

"The trade unions, I think, grew quite complacent in the postwar era," Arnesen told Fox News. "The organizing esprit of the 1930s faded. Unions became bureaucratized to a large degree. They delivered for their members but the larger social vision -- that was reined in a little bit."

Arnesen said union leaders have begun to grasp their need to adapt to changing demographic realities. This has meant focusing more of their money on recruitment, and targeting Latino workers for unionization efforts in the growth sectors of retail, fast food, and health care.