Hospital bedside graphic (AP)

The state House in Oregon is expected to vote early next week on whether to impose a crackdown on companies that sell so-called "suicide kits," which contain hoods or other items intended to help a person end his or her life.

The bill was proposed in response to the death of a 29-year-old Eugene man, Nick Klonoski, who killed himself using a suicide kit he ordered through the mail from a California company.

The state Senate unanimously approved the bill Monday.

Kits like the one Klonoski used cost $60 and contain a plastic bag that fits over the head, along with plastic tubing that can be attached to a tank of helium gas. They can be purchased by anyone at any time, without the consultation of a doctor.

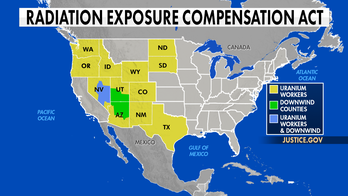

Oregon is one of just a few states that allow doctors to help terminally ill patients end their lives early in certain circumstances. But lawmakers said companies and individuals who provide suicide kits should be prosecuted because they lack safeguards and take advantage of the vulnerable.

"We want to send a message, to make it very clear, if you are in the business of marketing or selling suicide kits to people, you will be held accountable," said Sen. Floyd Prozanski, a Eugene Democrat who sponsored the bill.

The measure prohibits the sale or transfer of "any substance or objects to another person knowing that the other person intends to use" it to commit suicide. Lawmakers said it was especially important to pass the bill because minors could easily access information about suicide kits online.

Robert Gebbia, executive director of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, said he believes the Oregon bill is the first of its kind. But he said it's "something we're going to start seeing more of, because there's just so many of these groups springing up ... promoting suicide."

In 1994, Oregon became the first state to enact a law that lets terminally ill people end their lives by taking lethal medication supplied by a doctor. In 2010, 65 Oregonians took their lives under the law, according to the state's Public Health Division. Physician-assisted suicide also is legal in Washington and Montana.

Oregon voters are strongly in favor of the law and have supported it in two ballot measures since 1994.

But state lawmakers were appalled by Klonoski's death, which drew attention after a March story in The Register-Guard of Eugene.

Klonoski, a graduate of South Eugene High School and the University of Michigan, was depressed from bouts of pain and fatigue, the newspaper reported. He bought a "helium hood kit" from The Gladd Group of La Mesa, Calif., and rented a helium tank from a local party goods store. He used the kit and tank to end his life by helium asphyxiation in December. His family could not be immediately reached for comment Monday.

The Gladd Group's 92-year-old owner said the bill has given her a lot of publicity and that kit sales are up to 60 a month from people all over the world. Sharlotte Hydorn of El Cajon, Calif., said she has sold about 30 to Oregonians since the bill was introduced in January.

The company has been in business for three years and previously sold about two kits a month.

"I frankly don't care if that law passes at the end of it," Hydorn said. "I have no anger and no resentment. Oregon is free to do as Oregon wishes."

She said she would stop selling the kits, which take five hours to make, to Oregonians if the law prohibited it. Gebbia said providing suicide kits to someone who is "vulnerable" may make it easier for them to end their lives when they should get help.

He said the U.S. House of Representatives is looking at a bill that would make it a crime to provide information that encourages a person to take their life, based on the case of 19-year-old Suzy Gonzales in California, Gebbia said. The college student killed herself in 2003 after following instructions online.

Hydorn said that in the case of minors ordering the kit, it is the responsibility of the parent to monitor and take care of their children.

She said she started selling suicide kits because she wanted to help people who were terminally ill. "People are tired too. It costs a lot to die, if you want to do it the proper way," she said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.