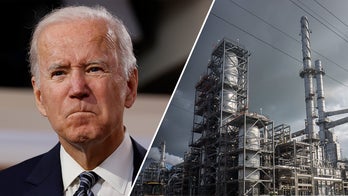

This October 2008 photo shows the Fukushima No. 1 power plant of Tokyo Electric Power Co. at Okuma, Fukushima prefecture, northern Japan. (AP) (AP2011)

The United State has offered to help Japan deal with a nuclear reactor whose cooling system failed after a power outage caused by Friday's massive earthquake off northeastern Japan.

At a news conference Friday, President Obama said he asked Energy Secretary Steven Chu to provide any assistance necessary. He added that he told Chu to "also to make sure that if in fact there have been breaches in this safety system on these nuclear plants that they're dealt with right away."

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said Friday morning that U.S. Air Force planes were carrying "some really important coolant" to the Fukushima Daiichi plant. But apparently she misspoked.

"We cannot verify any U.S. military involvement in delivering coolant to Japan," Pentagon spokesman Col. Dave Lapan said six hours later, adding that perhaps others in the Japanese government provided it.

Japanese nuclear officials say radiation levels inside a nuclear power plant have surged to 1,000 times their normal levels after the cooling system failed.

The nuclear safety agency said early Saturday that some radiation has also seeped outside the plant, prompting calls for further evacuations of the area. Some 3,000 people have already been urged to leave their homes.

The continued loss of electricity has also delayed the planned release of vapor from inside the reactor to ease pressure. Pressure inside one of the reactors had risen to 1.5 times the level considered normal.

To reduce the pressure, Japanese authorities released slightly radioactive vapor. The agency said the radioactive element in the vapor will not affect the environment or human health.

David Albright, a former weapons inspector for the United Nations, told Fox News that when a nuclear reactor is safely shut down, there is still a lot of radioactive material in the core that produces heat.

"If you don't extract that heat with cool water, it can reach a point where it can melt the fuel," he said. "It's an urgent matter to get the cool water flowing through the reactor."

After the quake triggered a power outage, a backup generator also failed and the cooling system was unable to supply water to cool the 460-megawatt No. 1 reactor, though at least one backup cooling system is being used. The reactor core remains hot even after a shutdown.

The agency said plant workers are scrambling to restore cooling water supply at the plant but there is no prospect for immediate success.

If the outage in the cooling system persists, eventually radiation could leak out into the environment, and, in the worst case, could cause a reactor meltdown, a nuclear safety agency official said on condition of anonymity, citing sensitivity of the issue.

But Albright said that risk appeared to be "very small from the available reporting."

"But nonetheless, you can still have a buildup of radioactive gas, and you can have a buildup of pressure," he said. "Sometimes they want to release that pressure by venting, perhaps a containment dome."

Another official at the nuclear safety agency, Yuji Kakizaki, said that plant workers were cooling the reactor with a secondary cooling system, which is not as effective as the regular cooling method.

Kakizaki said officials have confirmed that the emergency cooling system -- the last-ditch cooling measure to prevent the reactor from the meltdown -- is intact and could kick in if needed.

"That's as a last resort, and we have not reached that stage yet," Kakizaki added.

He said both the state of emergency and evacuation order are meant to be a precaution.

"We launched the measure so we can be fully prepared for the worst scenario," he said. "We are using all our might to deal with the situation."

Defense Ministry official Ippo Maeyama said the ministry has dispatched dozens of troops trained for chemical disasters to the Fukushima plant in case of a radiation leak, along with four vehicles designed for use in atomic, biological and chemical warfare.

High-pressure pumps can temporarily cool a reactor in this state with battery power, even when electricity is down, according to Arnold Gundersen, a nuclear engineer who used to work in the U.S. nuclear industry. Batteries would go dead within hours but could be replaced.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.