“Where exactly are you from?” It's a question I've navigated my entire 27 years of existence. The process of answering has always gone down like this: “Well, Colombia. (stutter) Actually, my parents are from Colombia but I’m from Dallas. (stutter) Well, technically I was raised Colombian so I'm not really a Texan.”

This is the least complicated part of the entire conversation. It’s watching them trying to piece their response together that usually requires some patience on my part.

I find the perception of an entire people is being easily manipulated by echoes of anger and political slogans. Sure, a vote or two today might make the difference between a win or a loss, but what about the impact it has on tomorrow?

In New York, the follow-up is usually, "You must be Italian, right? Your last name’s Pinilla." In Texas it was always, "You speak Mexican, so you must be from Mexico right?” Sure, I'm an American kid raised in the late Nickelodeon 90s and nostalgic about the same cookie crisp Saturdays like anyone else except my tale’s got a few twists and bumps attached to it.

Let me explain. I’ve got a few early memories still engrained in my mind that are pretty difficult to erase. The earliest one is of my grandparents taking me out for a day at Disney World. For most families in Colombia, the United States is quite simply Disney, Orlando, and New York City. Perhaps it’s because these were easy destination hubs to fly to. However, Disney was not the place we called home. Instead, my family emigrated “deep into the heart of Texas” to a small rural community known as Garland, Texas.

You can thank the movie Zombieland for ultimately giving it a slight bit of fame.

- Julissa Arce’s story: From intern to Wall Street executive – all while undocumented

- Trump campaign says plans for massive deportations yet ‘to be determined’

- Ali Noorani: On Trump and immigration, details please

- Undocumented immigrants paid up to $5K for a driver’s license, court papers show

- Opponents of AZ immigration law agree to deal allowing officers to question status

- U.S. Latinos struggle to keep the next generation speaking Spanish at home

- Hispanic Heritage Month kicks off! A time to be proud, a time to be grateful

- Despite language and cultural barriers, Latinos and Muslims in Elizabeth forge civil relations

- Wooing Latino voters: Non-Hispanic politicians who speak Spanish

It is here in Garland where I spoke my first word, took my first step, and unfortunately, experienced my first taste of isolation. It was first grade, I was a 6-year-old sitting on a school bus, tears in my eyes. Separation anxiety was a huge issue for me in the early days of elementary school. An older child sat in front of me, olive skin, bleach blonde hair, bowl-cut. He was a confident fellow, bluntly turning around and asking me if the woman waving goodbye was my mother. When I replied, his reaction stunned me. He said I sounded funny. He wondered why I was going to his school because I didn’t really sound like him.

See, I was born here, but that doesn't necessarily mean that I was born speaking English. When a parent raises a child, they not only have to teach basic skills like walking and talking, they also have to teach language. Now picture yourself as a young parent, two years into a new country trying to absorb a new way of life, a new native tongue, and then doing your best to teach that new language to your 2-year-old son. So yeah, I was a first-grader fluent in Spanish and learning English with my folks simultaneously. I spoke funny.

With a little bit of retrospect, I’ve come to realize that we as a family placed ourselves in what I call “bubbles of safety.” Our little bubble consisted of my grandparents' home (strategically housed as neighbors in the same apartment block) my aunt and her kids, and us. These were the places that retained familiarity as a newly emigrated family. That's all we knew.

My grandmother would clean houses and my aunt and mother would tag along to make some cash. I remember once seeing this awesome Power Ranger collection up on a shelf at one of the houses my mother was mopping up. It was “take your kid to work day.” I played for hours with them. Essentially, I was renting this kid’s lifestyle. It felt like a trial of what could be... and then back home we went.

Yes, I saw the major difference between the five-bedroom, two-floor home my mother spent hours cleaning and the one-bedroom apartment we called home. This made a major impression on me.

We barely navigated outside that bubble. My only real friends were my grandfather and cousin.

From my point of view, that was enough.

For me, the idea of seeing a classmate outside of school was odd. The fact that kids were hanging out at each other's homes or that fifth-graders could date was weird. This was so embedded in me that when I finally started to acclimate myself to the American lifestyle, I felt almost ashamed to tell my parents.

As a matter of fact, it was very rare that my family would ever know about any “girlfriends” or “recaps of my school days” because anything of the sort seemed like a betrayal of that bubble.

Perhaps this is the reason why to this day, I don't even respond to a word my sister says in English, much less my parents. It'd be too weird. It would feel deceptive of that “safe space.”

Homecoming and prom were things unheard of. Led Zeppelin and the Beatles?, save that discovery for the college years. The only impression of music I had as a child consisted of Carlos Vives and a few “Villancicos” come Christmas time. Movies were subtitled, which gave me an appreciation for the written word. Clothing was just that, items to keep you clothed. There was no such thing as trendy fashion. Marshall’s and Gap were as far as it went. Football on Mondays? No way. It was the cadence of Andres Cantor for hours on end narrating a game or two that filled up our home.

Keep in mind, these memories are still of the early days. My struggle in defining who I was didn’t really begin until adolescence. See, in elementary school we had what I now refer to as “systemic segregation.” This might come off as a strong definition, but let me explain.

The kids who were “white” and English-speaking were in one class, and the kids who were Hispanic had their own. Now, as an adult, I realize these were the "English-as-a-second-language,” or “E.S.L. kids,” but the derogatory term my fifth-grade classmates used was "the Mexicans." God forbid there was ever any interaction between these two. And so I found myself in a weird spot. Half the time I was asked why I wasn't "with the Mexicans" while the other times three of my Hispanic classmates from the E.S.L. classes would refer to me as “white boy.” I was conflicted.

There were moments when our teacher would try to get me to say something in Spanish so the whole class could learn and, shamefully, I would be embarrassed. I would do my best impersonation of that Michael Bloomberg "gringo" accent to try to sound more like the white kids around me when they said words like row-ho or uh-zool. (Correctly pronounced rojo and azul).

It wasn't until I was a teenager that I learned to appreciate where I came from and actually took that pride seriously. So much so that I would even play to people's fears and exploit their prejudices for my own amusement. IE: I walk into a store, not speaking English while I purchase something at the register. I would act confused, sometimes agitating the person behind the counter. I’d tempt the clerks or someone around to say a nasty remark about me. Then, as I would exit the store I would say “thank you very much, have a solid day!” in that “white boy” persona I was always accused of. (This is a tactic I still have fun with to this day).

I guess it took me years of living a few thousand miles away from Texas to properly analyze why I never felt at home. Honestly, the best explanation I have is that I was born in one place but raised as if I was from another.

I share these memories and my perspective because like myself, and the millions of immigrants around this country, we all have our bubbles, our safety nets, our pieces of home away from home ... but we’re Americans too. And this unique tale of contrasting cultures living amongst each other is exactly what our democracy was founded upon. Where we come from there is no "white" or “black” or “Latino” or the various groups that this country chooses to define with. There is only poor and not poor. And unfortunately, poor is our majority.

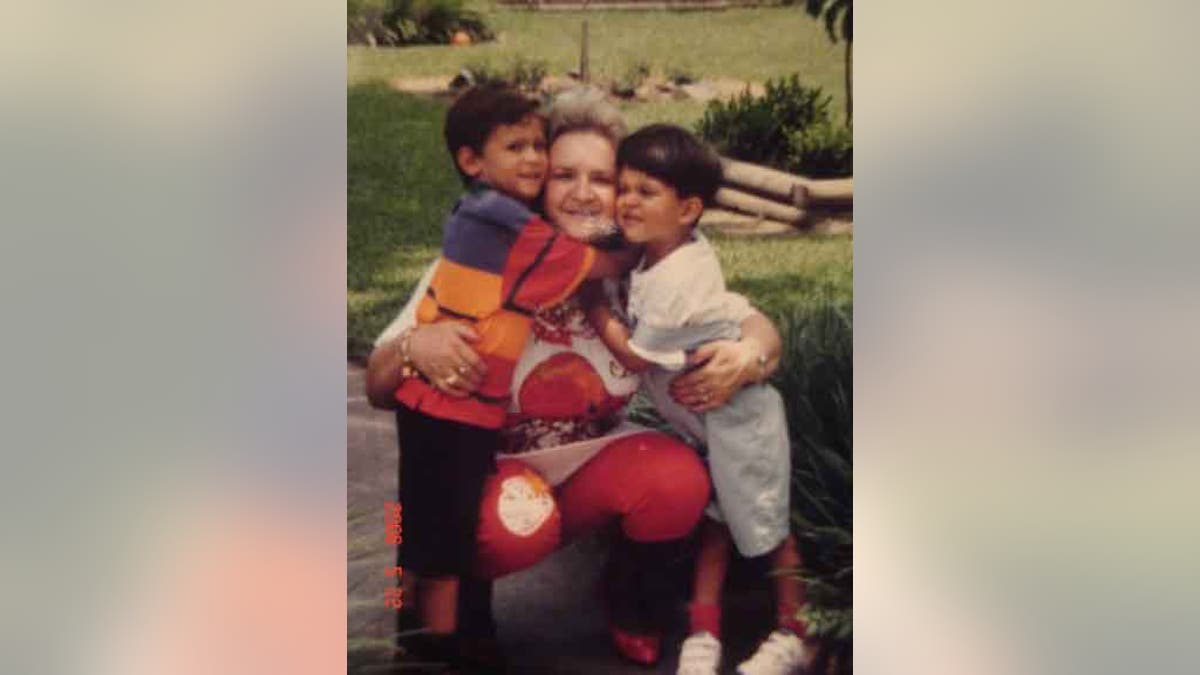

This is precisely why we chose here. America. It is why two young parents trying to sort their lives out decided to raise their child here. Maybe one day that child could be a lawyer, a doctor, or a storyteller with a lens (god forbid). We are important to the growth of this country and are essential in forming our more perfect union.

We cannot be treated like a "voter block" or that invisible “boogey-man” to blame when economic hardship lingers. We shouldn’t have our first-grade kids dealing with the notion that they “sound funny.” Teenagers trying to figure out their place in the world shouldn’t have to listen to their classmates claim that our grandmothers should speak English because they “live in America. We speak American.”

Children of parents from another place shouldn’t have to imagine their Aunt “Lilia” one day being taken away because some politician’s trying to score some political points.

Now, of course there have always been several counter-arguments to the perspective I share with you.

Some examples include, “Well, we’re not talking about you or your grandparents, Jeff. We’re talking about the bad ones. You know, the one’s who are committing crimes and causing danger in our streets.”

So I’ll leave you with a final story:

One summer afternoon, my mother was called for a cleaning gig. It was a last minute request for a three-bedroom house. It would only take a few hours so it would be some easy cash. She arrived, placed her gloves on, and worked her tail off the way she always had.

A week later, police show up claiming she’s suspected in having stolen some jewelry from the house. After consulting with a lawyer or two, the recommendation was that she plead guilty and cooperate to avoid major repercussions.

Sadly, she almost agreed. The pressure was intense. Imagine everyone telling you that you committed a crime to the point of actually believing it yourself. It wasn't until a few days later that investigators realized the homeowner accusing my mother was committing insurance fraud. See, this was an instance where my mother, a working immigrant woman raising a child, was easily framed up as “one of the bad ones.” She was the scapegoat. Tossing the blame on her was simple and clean because she was a vulnerable target. She, in the minds of everyone, was a criminal.

I share these stories because words matter. I find the perception of an entire people is being easily manipulated by echoes of anger and political slogans. Sure, a vote or two today might make the difference between a win or a loss, but what about the impact it has on tomorrow? The words a first-grader used when speaking to me on the bus in 1994 were bred in innocence, but I can't help but wonder what that conversation would have been like today.

Our kids mirror the things we say and the words we express. If I, as a 27-year-old man, still remember the moment another child said I spoke funny, imagine the impact that could have had if the accusation and the language was a bit more aggressive. If my mom took that plea just to release herself of the pressure they were putting on her to say “I did it,” would they have taken her away from me?

I get that it's easy to say "ship them all out"! or "they're the problem" and it's lazy to think "they're all taking our jobs."

Until one day you realize that “they” are your neighbors, your colleagues, your kid’s soccer coaches, your dentist, your middle school teacher’s, and your child’s best friend.

And for once in my life I've got an answer to that question I’ve always found myself stumbling to answer:

Yeah I was born here. But g#% damn it I was born there too!