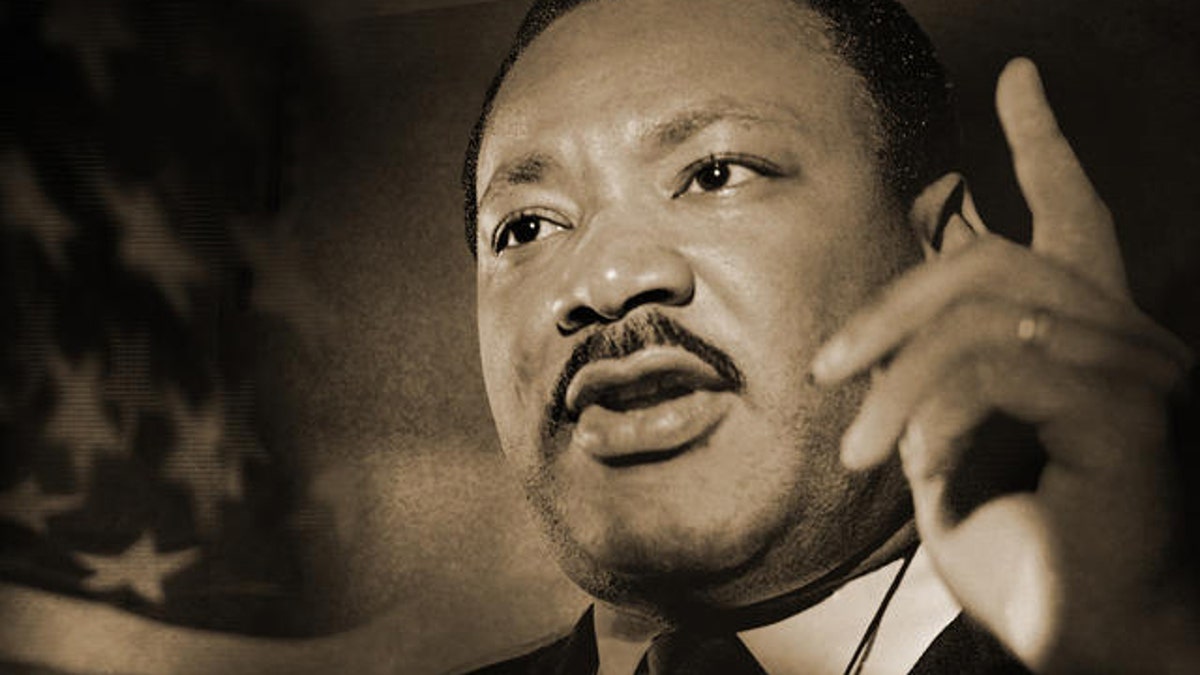

Armed with a handful of warmed-over sermons and big dreams to grow a small church, the newly ordained Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. arrived at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala., in May of 1954. According to biographer Richard Lischer, King came to Dexter with a 39-point plan that included the purchase of a new pulpit. The two pulpits the church owned – one in the sanctuary and the other in the basement for use in Sunday School – had virtually been there since the last brick was laid in 1889.

Within a year of his arrival, King was the recognized leader of America's protest for civil rights. America was marching for change, and King had become more than the pastor at Dexter. But he never stopped preaching. In fact, he believed the church was the center for necessary, creative, loving change. The rhetoric that soared at state houses and national monuments was birthed in the pulpit.

Earlier this month, I toured Dexter Avenue, along with 19 other ministers of my faith. Ten of us are white; 10 are African-American. We believe that race is an issue in our churches and country. Who could deny it? From bursts of outrage over the shooting of Walter Scott by Michael Slager, to Dylan Roof's alleged hate-filled mass-murder at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, to garish and schismatic rhetoric regarding immigration, racial tensions still texture American life. And it's past time for churches and church leaders to own up to our responsibilities.

In this moment, Christians of all varieties should join King in embracing what the Apostle Paul called “the ministry of reconciliation.” When faced with racial divisions, the writers of the New Testament claimed Jesus was the one “who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility.” The heart of the Christian lifestyle is deploying the reconciliation we have through God and extending it so others may be reconciled both to God and one another.

From bursts of outrage and explosive responses over the shooting of Walter Scott by Michael Slager to Dylan Roof's insanity-fueled mass-murder at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church to garish and schismatic rhetoric regarding immigration, racial tensions still texture American life. And it's past time for churches and church leaders to own up to our responsibilities.

Reconciliation is the substructure of Christianity. It was Jesus who said, “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.” And he didn't mean to pray for their demise – that's a curse, not a prayer. As we embrace Christ, we can ill afford the pettiness, protections of privilege and partisanship that rip the fabric of American life. Spiteful words, knee-jerk reactions, social media posts that carve the world into “us” vs. “them” and utterances of half-truths about “those people” work against the ministry of reconciliation.

God desires our freedom from sin and urges us to reconciliation because He loves our neighbor and wants us to see His image and beauty in others. Cultural, ethnic and racial divisions are not simply a breakdown of government or culture. They are a dismissal of the Gospel.

Dr. King never got his new pulpit. The seeds of the civil rights movement blossomed too quickly, and like most old furniture in churches, the deacons decided the gear they had was good enough. After marching from Selma to Montgomery, King found Dexter Avenue’s basement pulpit plenty sturdy. Standing behind it, foot-worn and fatigued, he called "clergymen and laymen of every race and faith" to pilgrimage together. The reconciliation preached at Dexter Avenue became the reconciliation preached at the base of the Alabama Capitol steps. It was a journey of a million strides, though the two buildings are only steps apart.

That's the way meaningful transformation happens. If it's true, good, and beautiful, it begins with Christians. It begins with church.