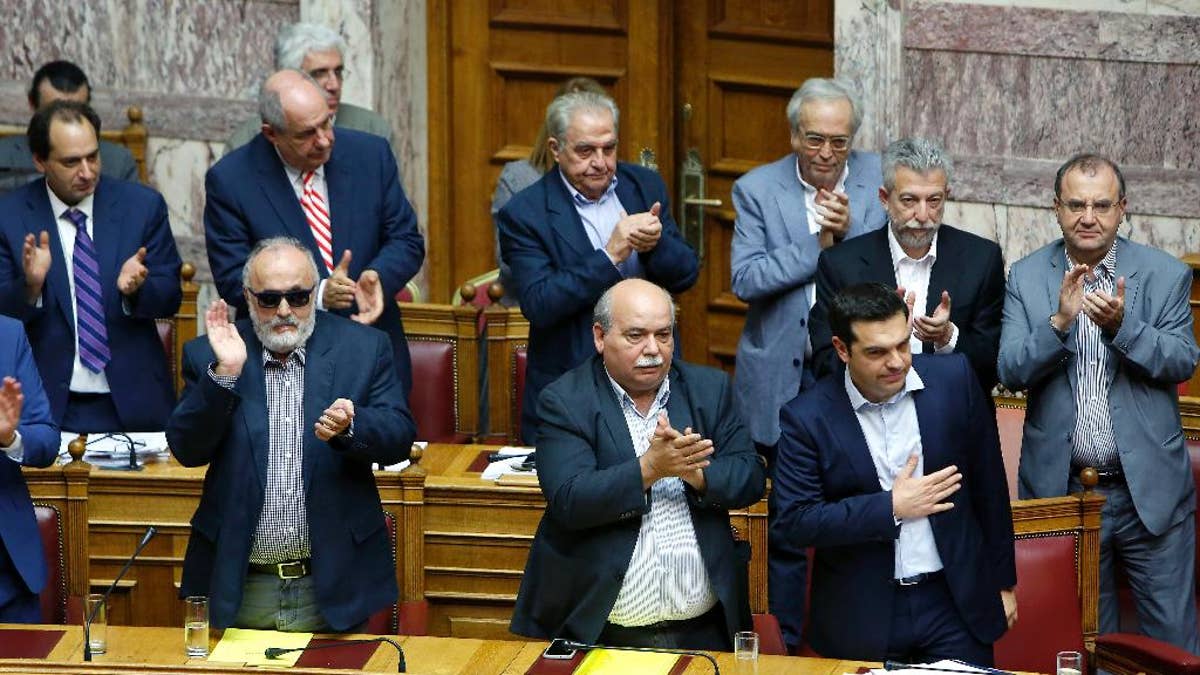

Ministers of Greek government applaud the Greece's Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras after his speech in an emergency Parliament session for the government’s proposed referendum in Athens, Saturday, June 27, 2015. Greece's place in the euro currency bloc looked increasingly shaky on Saturday, when eurozone countries rejected a monthlong extension to its bailout program and the prime minister called for a risky popular vote on the country's financial future. (AP Photo/Petros Karadjias) (The Associated Press)

The financial crisis in Greece has reached the moment of truth. Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras called a referendum July 5 on whether to accept the EU's last offer of policy conditions for a bailout disbursement. He is asking for a "no" vote.

Tsipras also told his Parliament and world financial markets that Greece would not make the 1.6 billion euro payment it owes the IMF by the today's deadline [June 30]. The IMF accordingly will declare it in default. And the European Central Bank decided over the weekend to deny any more emergency liquidity assistance to Greek banks. To stem panic and a bank run, the Greek government announced capital controls, including a daily limit on withdrawals. Worried Greeks have lined up for cash, there are reports of hoarding of food and gasoline. Around the world, investors have the jitters, including on Wall Street where the Dow Jones Industrial average dropped more than 350 points yesterday [June 29].

Last week, despite a ballyhooed Greek offer, Eurozone countries and Greece were unable to reach an agreement on measures Greece would take in order to receive the last $7.9 billion of bailout money that was originally part of the package approved by the EU in 2012.

The problem has been years in the making. The outcome will have broad consequences for the already-devastated Greek economy and, to a considerable extent, for the rest of Europe. The core problem is less about economics than about politics.

The European Union, the European Central Bank and the IMF have put tough conditionality on disbursements of bailout money to Greece because their publics demand it, and because they believe -- not without reason -- that easier conditions would be seized by Greece to fall-off of its agreed upon austerity program, and might encourage other European countries to adopt populist policies as well.

However, these tough-minded EU policies helped Syriza win power in Greece in January 2015. They played to a narrative on the Greek left which held that capitalist northern Europe never would let them out of the austerity strait-jacket and so Greeks must stay firm, and as the Prime Minister asks, say "no" in the referendum.

What will happen next? If the Greek public supports the Prime Minister and votes "no" on the referendum, it isn't likely other European publics will be moved to offer Greece better terms. More likely would be the interpretation that Greece is now prepared to leave the euro for good, no matter what the consequences. Greece would be forced to introduce its own medium of exchange, like a new drachma, or use the euro as its currency without any access to the European Central Bank resources (as Montenegro does now, for example). It is hard to see any new domestic or foreign private investment in Greece in such a scenario for some time to come. Ultimately the Syriza government would likely fall as a result of the dire circumstances, but a new government would have a steep hill to climb.

If the Greek public votes overwhelmingly "yes," then one might expect the Syriza-led government to fall immediately, either by resignation or because the party splits apart. Uncertainty would also increase, but a government of national unity may emerge more quickly, perhaps led by a technocrat as in 2012. Maybe Greece could use the occasion to address deep-seated governance problems to set the stage for renewed investment and growth. Maybe the EU side would give the Greeks the confidence that -- this time -- economic growth and renewed hope would be part of the bailout package