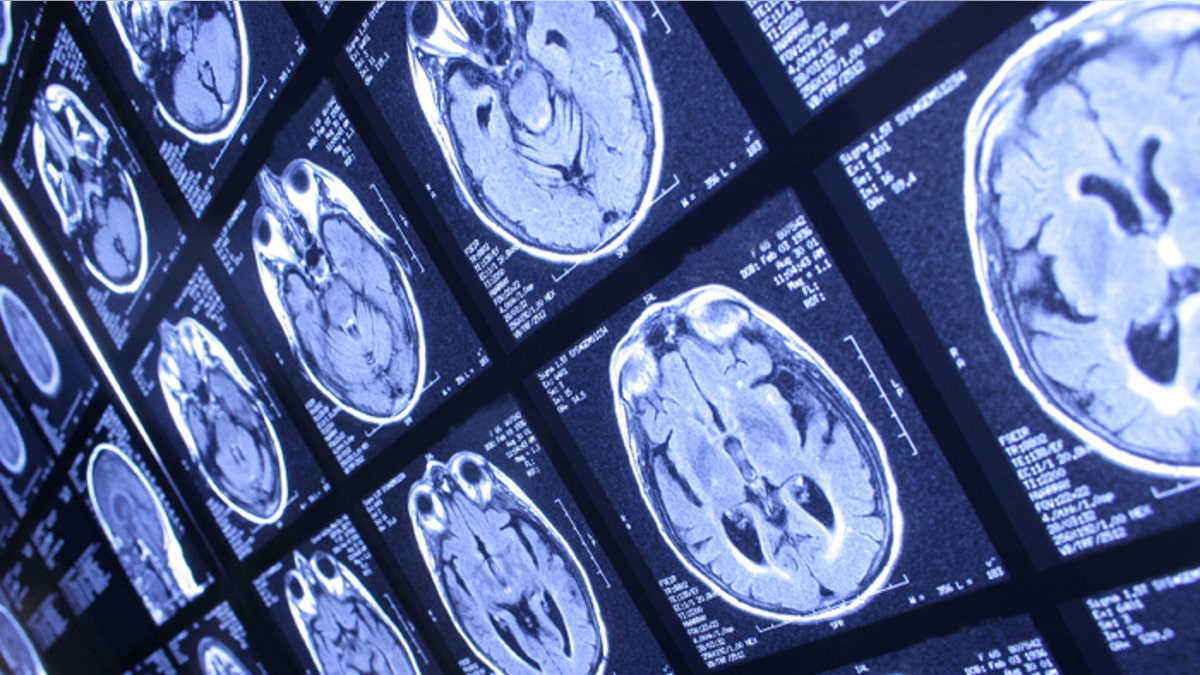

A new MRI technique could help doctors diagnose dyslexia in children before they even begin reading, according to new research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

The findings, published in the Journal of Neuroscience, may lead to earlier intervention techniques for children, which could ultimately make treatments more effective.

About 10 percent of Americans suffer from dyslexia, a learning disability that can impede a person’s ability to read, write and even speak. The condition is usually diagnosed in second grade after a child has already experienced difficulty with written language.

In collaboration with researchers from Boston Children’s Hosptial, MIT researchers identified a link between poor pre-reading skills in kindergartners and the size of a brain structure known as the arcuate fasciculus – an area of the brain responsible for connecting two-language processing areas. Previous studies have found that this structure is smaller and less organized in adults with poor reading skills.

However, scientists did not know if the size of the arcute fasciculus caused people’s problems with reading or was the result of a lack of reading experience.

Using a technique known as diffusion-weighted imaging (based off of MRI), the researchers analyzed the brains of 40 children between the ages of 4 and 6. They found that the children who scored lower on phonological tests had smaller arcute fasciculus volumes. Phonological awareness relates to a child’s ability to identify and manipulate the sounds of language.

To better understand how the arcute fasciculus develops over time, the researchers hope to follow three waves of children as the progress to second grade, in order to see if this brain scanning technique truly predicts dyslexia.

“We don’t know yet how it plays out over time, and that’s the big question: Can we, through a combination of behavioral and brain measures, get a lot more accurate at seeing who will become a dyslexic child, with the hope that that would motivate aggressive interventions that would help these children right from the start, instead of waiting for them to fail?” study author John Gabrieli, professor of brain and cognitive sciences and a member of MIT’s McGovern Institute for Brain Research, said in a press release.